Last week we announced that Noel Hynd’s FLOWERS FROM BERLIN was our new Romance of the Week and the sponsor of thousands of great bargains in the Romance category: over 200 free titles, over 600 quality 99-centers, and thousands more that you can read for free through the Kindle Lending Library if you have Amazon Prime!

Now we’re back to offer our weekly free Romance excerpt, and if you aren’t among those who have downloaded this one already, you’re in for a treat!

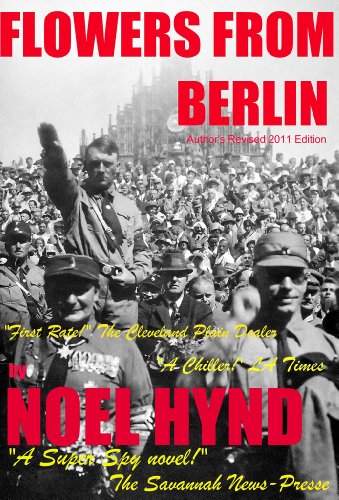

International Best Seller. Rights sold in UK and Japan. Spanish and French language editions coming in 2012.

The classic American spy novel, from the author of, “False Flags: Betrayal in London,” “The Sandler Inquiry: A Spy in New York” and “Hostage in Havana.”

Love and betrayal, spies and patriots, murder and romance, Roosevelt versus Hitler on the eve of World War Two. “Winds of War” meets “The Eye of The Needle.”

This 1985 espionage thriller follows FBI agent William Cochran’s efforts to stop a Nazi spy from assassinating FDR. Toss in a love affair with a British Secret Service operative and you have the makings of a page-turner. LJ’s reviewer found the book “complex in characterization, crisp in dialogue, and thorough in its background” (LJ 3/15/85).

“First rate!” – The Cleveland Plain-Dealer

“A Chiller!” – Los Angeles Times

“A Super spy novel!” The Savannah News-Presse

It is 1939. Roosevelt is winding down his second term in the White House. The Nazis have taken Austria, and Stalin’s Red Army is systematically eliminating the Kremlin’s enemies. Europe is going to hell in a handbasket. With isolationist sentiment running high in America, and the president’s popularity at an all-time low, Hitler seizes the moment and dispatches his secret weapon: An agent named ‘Siegfried’ who conceals himself behind the mask of middle-class America. A chameleon who can change identities and personalities at will. A cold-blooded killer who will win the war for Germany.

A banker, linguist, and demolitions expert who has successfully infiltrated German intelligence, FBI Special Agent Thomas Cochrane is handpicked by Roosevelt for an impossible mission: To find Hitler’s spy before he carries out a plan that will remove the president from office at a critical moment in the century’s history. As Cochrane, with the help of British Intelligence agent Laura Worthington, circles closer to his elusive quarry, a spy with supporters in the highest levels of U.S. government readies the world stage for a final act of annihilation that will alter the tide of war–and the future of the free world–in unthinkable ways.

Imagine a world where your most precious inalienable rights are denied. Where individual freedom is a thing of the past. Imagine World War II without FDR …

735,000 first mass market paperback printing.

And here, for your reading pleasure, is our free excerpt:

FLOWERS FROM BERLIN

Author’s Revised 2011 Edition

By Noel Hynd

William T. Cochrane, Banker and Educator, Dies at 90

By Abigail McFedries (Special to The New York Times)

Published: November 28, 1996

William Thomas Cochrane, an economist, author, banker, retired F.B.I. agent and university professor, died on Thursday at his home in Newton, Massachusetts. He was 90.

The cause was a cerebral hemorrhage, said his daughter, Carolyn.

Mr. Cochrane enjoyed a long and distinguished career in several fields spanning the Twentieth Century. He was most proud, however, of his little known service to his country during World War Two……

Cambridge,

Massachusetts

May 1984

PROLOGUE

Memorial Hall, on the fringes of Harvard Yard, is the quintessence of old-guard university architecture. Ivy climbs its aged white columns and red brick walls in abundance. Built in tribute to the Harvard men who perished in wartime, the hall maintains a quiet, timeless dignity amid the bustle and clamor of Cambridge. Yet on the final day of spring term in May of 1984, even Memorial Hall was alive with excitement. Students who might otherwise be on their way to the Cape or to the beaches of the North Shore on an impeccably sunny morning were busy jockeying for seats in the great lecture hall, rousing and crowding out the ghosts of other eras.

Undergraduates had completely packed the sprawling, multi-tiered amphitheater by 10 A.M. Political Science 217 was concluding for the semester. Today was the final lecture. But it was the lecture, the one Dr. William Thomas Cochrane of the Economics Department gave every year. And every year, as the students put it, it was a “sell out.” No extra places in the eight-hundred-seat hall, even though the topic was never covered on final exams.

Dr. Cochrane gave the lecture each year because it added that ineffable extra insight into the course. It put things in perspective. Poli Sci 217. American Political Systems in Wartime; 1917-18,1941-45. Today’s topic, “Roosevelt and the World War.” Harvard students had their own nickname for the close-out lecture: “Poli Spy 217.” Even at age seventy-eight, Bill Cochrane could still pack a house.

Dr. Cochrane entered the lecture hall a few minutes before ten. He was a man comfortable in tweeds and a tie and who wore his age with equal grace. Tall and sturdy, his shoulders were still straight. His hair was thinning and flecked with gray, but surprisingly dark. His one concession to age: reading glasses of a stronger prescription than he had worn back when he had worked for the government— below cabinet level during the Eisenhower and Kennedy years.

There was a woman a few years younger than the lecturer seated at the far left of the first row. Had she opened her mouth to speak, they would have known she was English, though she had spent the last half century losing the intonations of her birthplace. She was, had anyone looked closely, the paradigm of the patrician English lady of her day. She had a pleasant face and a clear complexion. She wore a dark green cardigan sweater and a wool skirt. A few years earlier, she had given up the pretense of chasing age from her hair, so now she was very frankly gray. But her hair was arranged in a neat bun and she remained very pretty in an uncommon, aristocratic way. Men who noticed her did not immediately take their eyes off her. It had always been that way.

At 10 A.M., without a cue, the students quieted. Copies of The Harvard Crimson rustled as they were folded into notebooks. Dr. Cochrane looked up from the lectern—he always spoke without notes— removed his reading glasses, paced a few feet from the front center of the hall, and in his unmistakable yet unassuming way took control of the class.

“Roosevelt and the War,” Dr. Cochrane said by way of introduction. He spoke in a clear, concise voice. “You’ll allow me, I hope, a bit of historical speculation over the next ninety minutes. You will indulge me, I hope, the opportunity to suggest what might have been, in addition to what was.”

He paced thoughtfully near the front row of students. He felt his audience settling in with him.

“For any of you who are recent transfers from New Haven or any other institution,” he digressed momentarily, “we are discussing the second Roosevelt. And the second world war.” A ripple of laughter eased across the amphitheater.

“August 3, 1939,” the popular emeritus professor began, recalling his material vividly. He spoke in a bold voice that filled the hall. The students were already entranced. The Englishwoman permitted herself a smile. She remembered also.

“Washington, D.C. Ninety-one degrees of city-wide steam bath for the fifth day in a row. . .”

PART ONE

Washington, D.C. and New York

1939

ONE

August 3, 1939. Washington, D.C. Ninety-one degrees of city-wide steam bath for the fifth day in a row. A relentless sun and humidity unfit for any living, breathing creature. Six more weeks of summer in the American capital and not an evening breeze or a thunderstorm in sight.

The windows were open at the White House and fans whirled in more than a hundred rooms. Fifteen minutes remained before a luncheon meeting between Secretary of State Cordell Hull and the President. Franklin Roosevelt sat in his wheelchair in the Oval Office and studied the disturbing four-page report that he had received that morning. These days the President’s mood matched the weather, hot and oppressive. Neither seemed likely for sudden change.

Europe was going to hell. The Nazis had taken Austria and had been given Czechoslovakia. Salazar was entrenched in Lisbon, and Franco had taken Madrid in March. Hitler lunched with Mussolini on a fourth-century A.D. veranda in Rome, and Joseph

Stalin, freshly invigorated by the liquidation of his enemies at home, folded his arms on a Kremlin balcony and glared westward. The Red Army, under Stalin’s direct command, was bigger, tougher, and better equipped than ever. But then again, Hitler had more panzer divisions than anyone could count already in place in Bohemia and Moravia.

At his desk, Roosevelt lit a cigarette. As soon as current work could be concluded, the USS Tuscaloosa, docked at the Washington Naval Yard, was ready to take FDR and his family to Campobello until September. The President longed for the foggy, misty New Brunswick coastline that he had loved since his boyhood. His sinuses bothered him; so did his arthritis.

Meanwhile, the Republicans imprisoned on Capitol Hill sniped daily at Roosevelt. A second Democratic term in Washington had failed to cure a 12 percent unemployment rate. And the 1938 elections had put the taste of FDR’s blood in the mouths of the opposition: the Republicans had gained eighty-one seats in the House of Representatives, eight seats in the Senate, and control of thirteen additional statehouses. Suddenly, new presidential prospects were everywhere. Ohio’s Senator Taft had won re-election big, as had governors Stassen of Minnesota, and Saltonstall of Massachusetts. New York’s racket-busting district attorney, Thomas Dewey, was drawing the largest crowds of any Republican since the President’s cousin, Theodore Roosevelt. And the influential eastern press was lining up behind the longest shot of all, Wendell L. Willkie, the president of a utilities company and a former Democrat.

Even members of Roosevelt’s own party were disgruntled. When would the President announce his own plans? Was he, or was he not, running for a third term? Even Eleanor, who had publicly professed her distaste for another four years in Washington, did not know.

“Eight years is enough for any one man,” she had said on June 6 in Chicago. On this and most other important matters, the President was keeping his own counsel.

There was no credible successor to carry forward the New Deal. The candidacy of Harry Hopkins was stillborn. John Nance Garner of Texas, the Vice- President and the darling of the increasingly powerful reactionaries within Roosevelt’s own party, was already campaigning. So were the six Republicans, equally rock-headed in Roosevelt’s opinion.

“Andrew Jackson,” Roosevelt was now telling Democratic leaders, “should have picked someone more in sympathy with his policies than Martin Van Buren if he had wanted his policies continued.” The history lesson was meant as a warning. But the party leaders were responding with their own warnings: Roosevelt was the only candidate who could hold

together the political coalitions in the North and the West in 1940. Roosevelt, they told him, was the only candidate who could prevent the nation from being turned over to the club-swinging isolationists.

“Would your husband consider a third term in order to further his concept of internationalism and the New Deal?” Eleanor was asked in Penn Station by a New York Journal-American reporter in July.

“You’ll have to ask him that question,” she had answered.

“But hasn’t he told you?”

“I haven’t even asked him,” the First Lady replied, stepping briskly into a private railroad car bound for Washington.

That evening in the capital, the pressures and political harassment evidenced themselves for the first time upon the President himself.

“Mr. Roosevelt? Would you even want a third term?” Walter Lippmann asked during an impromptu press conference.

“I don’t know, Walter,” FDR snapped back without a nuance of a smile. “But I’d certainly like a second one.”

And so it went.

Whatever his political concerns, no one could doubt the President’s equal concern with naval matters. And the report that he read on this sultry August morning before lunch was a classified document from the Department of the Navy.

All his life, Franklin Roosevelt had been fascinated by the sea and in love with ships. As Secretary of the Navy during the Great War of 1914-18, he had been so successful at securing materiel that President Wilson had once called him to the White House. There, the thirty-four-year-old Roosevelt had been gently reproached for his ardor.

“Mr. Secretary,” Wilson had said in his genteel, measured tones, “it seems you have cornered the market on supplies. I’m sorry, but you will have to divide them up with the Army.”

By the time Roosevelt had occupied that same office, he had collected no fewer than 9,879 books and pamphlets on naval matters. A few were housed in the library at Hyde Park. Several hundred were at Warm Springs, Georgia. But most were in the White House. When asked by an interviewer during the first term how many volumes he had actually read, Roosevelt replied, “All but one. But that one arrived last evening.”

Roosevelt ran his hand across his brow and reread the U.S. Navy report before him. He was deeply anguished. The HMS Wolfe, two days out of New York, had been ripped in half by an explosive device placed by a saboteur. The Wolfe had sunk in ninety minutes. Thirty-nine English merchant seamen had lost their lives, four of the five members of the French purchasing commission had gone down with the ship, and the entire cargo had been lost. Sabotage on the East Coast, the President concluded as his intercom buzzed, was totally out of hand. The President turned his wheelchair and answered the intercom.

“Mr. Hoover is here,” his secretary, Missy Eland, told him.

“Two minutes,” the President answered.

Waiting a few minutes was what J. Edgar Hoover needed these days, Roosevelt mused. The President eased his wheelchair back behind his desk and neatly placed the Navy’s report on his right-hand side. He readied himself for the meeting with the F.B.I. director, a meeting to which Hoover had been summoned one hour earlier.

Roosevelt disliked and distrusted Hoover. Hoover was a Republican, a Coolidge appointee dating back to 1924. But even worse, in the eyes of the current President, was Hoover’s greedy amalgamation of power within the newly formed F.B.I.. Hoover, it was known, had begun a grand collection of fingerprints and files, accessible primarily to himself. And still worse, Hoover seemed intent on building a political power base out of the recent successes of his agency.

Over the last few years, the F.B.I. had, through a combination of hard work, luck, and occasional diligence, captured several of the most notorious—and inappropriately romanticized—outlaws of the era since the stock market crash. One by one, Ma Barker, Baby Face Nelson, Machine Gun Kelly, Pretty Boy Floyd, and Bonnie and Clyde Parker had fallen into the hands of federal authorities. Always, Hoover was there soon after the arrest to link a hand onto the prisoner’s elbow and have his picture taken. Even when the F.B.I. hadn’t even been in on the capture, Hoover was there to claim credit. When John Dillinger, for example, had been shot to death outside the Biograph movie theater, a grinning Hoover had been in Chicago the next day to have his picture taken with the cadaver.

To Roosevelt, who knew a thing or two about power bases and who vastly preferred to have his own picture taken among boy scouts or WPA camp workers, such behavior was more than a trifle irritating. He had it in mind, in fact, to replace Hoover in another year. But meanwhile Roosevelt and Hoover were stuck with each other.

There was a knock on the door to the Oval Office and Mrs. LeHand was the first to step through. She ushered Hoover into the President’s working quarters, glanced disapprovingly at the F.B.I. director, and then closed the door as she left.

“Come in, J. Edgar, come in,” the President said, not looking up. Roosevelt sat at a desk that was neither very big nor very neat. Papers were in disarray in every direction and a half-empty can of Camels stood on the left-hand edge. Then Roosevelt glanced up, blinked, cocked his large head, and smiled. J. Edgar Hoover stared at what was—with the possible exception of Adolf Hitler’s—the most famous face in the world.

To Hoover, Roosevelt looked like a caricature of himself. The President’s face was tanned and mobile, his eyes never at rest. When he smiled, his mouth took the shape of a V, his long jaw tilted upward, and two long grave lines bracketed his mouth. His round glasses reflected like windowpanes in the sunlight.

“Do sit down, please,” F.D.R. said. He motioned to a leather armchair.

Hoover mumbled a good morning and sat down. He consciously tried to keep his eyes off Roosevelt’s withered legs, visible through the open front portion of the desk. Then Roosevelt adjusted his glasses slightly, as if to bring his visitor into proper focus.

The corners of Hoover’s mouth were turned ferociously downward. His neck was crimson, his collar tight, and his eyes afire. Shadows from the window behind Roosevelt darkened Hoover’s face, but made him squint at the same time.

“It would seem to me, J. Edgar,” the President began, “that there exists a certain gathering importance to this matter of German saboteurs and agents within the United States. Yet your Bureau appears unable to make the appropriate arrests.”

Hoover bristled instantly and opened his mouth to speak. Then he stopped. From the President’s intonation, Hoover knew there was more.

“Tell me, Mr. Hoover,” Roosevelt asked, “how does a saboteur, particularly the one whom your Bureau is searching for, creep onto a religiously guarded vessel, plant a bomb, and sneak off again?”

Hoover was about to answer, but Roosevelt kept talking.

“There is a man at large somewhere in America,” Roosevelt postulated, “who is both an expert at espionage and high-level explosives. He is costing us lives and he is robbing precious war materiel from the democracies of Europe. But he is an unnaturally clever man. Your F.B.I. cannot arrest him because you do not know whom to arrest. You cannot look for him because no one knows for whom to look. Indeed, the local police departments in the cities and towns of the Northeast cannot be used because we haven’t the faintest idea which ones should even be contacted.”

Hoover sat in silence. The President looked him up and .down. “Well, what do you think, J. Edgar?” Roosevelt asked at length. “You’ve barely said a word since you walked in here.”

“The Bureau,” Hoover replied quickly and defensively, “is working on this precise case day and—”

“Tell me,” said the President. “Do I misunderstand the situation or am I correct? What we need is a face. A name. Or a past. We must find out who this man is, where he came from, and what his background might be. All this is even more important than a current identity because this man would certainly be gifted also at changing identities.”

“That’s all correct, sir.”

Roosevelt continued to lead the conversation. “So what we are talking about is a bit of detective work. Identifying this particular man and locating him is the first task, without which any other plans are meaningless. And, of course, this work must proceed without alerting the suspect. Otherwise he will disappear and move elsewhere. Or return to Germany, perhaps.”

Mrs. LeHand buzzed the intercom again and notified the President that the secretaries of State and Interior were awaiting the President in the downstairs dining room. Roosevelt selected a fresh cigarette from the tin of Camels on his desk, placed it into a tortoiseshell holder, and slipped the holder between his teeth. Then he shifted uncomfortably in his chair, leaned back slightly, and lit his cigarette.

Then Roosevelt looked up again. “Tell me, J. Edgar,” the President said, “weren’t we successful several months ago in infiltrating a man into Germany? A man who returned some very good intelligence for us? He was a linguist and a financial man of some sort. Even had explosives training in the United States Army.”

“Yes, Mr. President. That’s entirely correct.”

“I believe he’s returned home, has he not?”

“Yes, sir.”

Now the President cleared his throat.

“Yes, of course,” said Hoover, as if to suddenly remember. “Naturally, the man is still employed by the Bureau. I believe his name is–”

“Cochrane,” Roosevelt said. “I recall. William Thomas Cochrane. Where is he?”

“He’s currently assigned to Baltimore.”

“Baltimore?” The President arched an eyebrow. “Doing what?”

“He’s in the Mid-Atlantic States Banking Fraud Division,” Hoover said.

Roosevelt added nothing for many seconds. “Really?” he finally breathed.

“I can reassign him this afternoon,” Hoover volunteered.

The President smiled widely and extinguished his cigarette, carefully removing the stub from the holder. “Very good, J. Edgar,” Roosevelt concluded. “I was confident that you would know exactly who should head this investigation.”

As if by magic, two Secret Service men appeared and moved to a position behind the President of the United States, preparing to wheel him to the luncheon for which he was already five minutes late. Hoover instinctively rose. The Secret Service agents, employees of the Treasury, ignored him completely.

“I think,” Roosevelt said in parting, “that you and I should meet again, J. Edgar. In about a month. I’d like to know how this saboteur has been captured.”

Hoover thought his ears were failing. “A month?” he asked.

“Good Gracious, Mr. Hoover!” Roosevelt suddenly roared, his chair halting, his face florid. “There’s a war breaking out in Europe! You don’t think we have all year, do you?”

PART TWO

Laura Worthington

England and America

1935-39

THREE

Laura Worthington’s earliest memories were of her own room in her father’s mansion overlooking Kensington Gardens. She must have been about four years old back then, she one day realized, because her father was home from the war and that was in 1918.

On the brown uniform of the British Expeditionary Force he had worn an assortment of ribbons and medallions. They were pretty to a little girl. He had hoisted her in his arms, and after she had joined her mother in embracing Papa, her fingers had wandered to the bright colors and the gleaming brass and silver. She was fascinated by them.

“Want them?” Major Nigel Worthington asked his daughter.

The little girl nodded excitedly.

He took them off his uniform, to the dismay of his wife, and removed the pointed ends of the pins. Then he placed them in a small ivory box that he had brought back from France for her. He set them on the floor and sat by approvingly. Thus, the Military Cross, the

Distinguished Service Cross, and the Victoria Cross, among others, became favorite toys for little Laura. She would pin them on herself and her dolls. A few days later one of the nursemaids of one of her playmates said that her father must have been very much of a hero to win all of those medals.

“Were you a hero, Papa?” Laura asked her father the next Sunday morning.

“No more than anyone else, Laura,” he answered. “Millions of men and women were in France. Almost all of them were very brave.”

“Why did they go?” she asked.

Nigel Worthington took a long look at his daughter. Then he picked her up in his strong arms—which she always loved—and carried her to the bay window of the mansion’s master bedroom.

Across the street, which was cluttered with carriages and new motorcars, were the gardens. It was a chilly November, so people were all bundled up as they strolled.

“That’s why, darling,” Nigel Worthington said, indicating an expanse of London beyond his window. “Because I love my country. And because England asked me to serve.”

The little girl contemplated her father’s words. “Can I be a hero, too, someday, Papa?” she asked.

He laughed and hugged her, nuzzling her neck. “Of course you can, sugarplum,” Dr. Worthington said. “Of course you can. Someday you can be a hero, too. For England.”

Laura Worthington was the daughter of a mildly eccentric London physician, Nigel Worthington, who had once been a renowned young surgeon on Harley Street, where he, his practice, and his patients all prospered together. Life, in the early part of the century, smiled upon him.

Before establishing his medical practice, he had been a brilliant student at Oxford, where he had read Modern Languages. He had taken time out during the Great War to serve with the First London Rifle Brigade and had been an artillery lieutenant at the Somme in July 1916. Nigel Worthington had again been lucky. During the darkest day in British military history—some 21,000 dead and 35,000 wounded during the Fourth Army’s futile advance toward German trenches—young Worthington escaped without a scratch. His only wounds, as he saw death all around him, were psychological.

Then a few years later, fate double-crossed him.

In early 1922, when his daughter, Laura, was eight years old, the influenza pandemic swept London. Laura’s mother, Victoria Worthington, went from perfect health to a cemetery within ten days. From there on, Nigel Worthington withdrew from the world that he had known. And he took his daughter with him.

He forswore his surgical practice and moved himself and his daughter to an enchanting, sprawling four bedroom Georgian house on the outskirts of Salisbury. Around the house was an acre of garden and around the garden was a high wall. Dr. Worthington kept hours as a general practitioner—he was known in the city as quiet, somewhat moody, but an excellent doctor. Yet he always knew that he could withdraw to his home and dedicate himself to the one thing he still cared about. It was not medicine, and not the comparative study of languages. Rather, he gave himself entirely to the raising of Laura, a beautiful little girl who, day by spectacular day, became an almost ghostly image of her dark-eyed, dark-haired mother.

Dr. Worthington hired a governess named Mrs. Frasier, who lived in and who was home when he had office hours or house calls. By now Laura was Nigel Worthington’s sole commitment in life.

From her father’s own voice and hand, Laura learned an appreciation of music and art, literature and philosophy. Nigel Worthington sat by his daughter’s side for hours—sometimes rescheduling patients to do so—to watch her growing fingers glide across the keyboard of a piano, exactly as her mother’s once had. He taught her about God and Christianity just as he taught her to respect all other people and their religions. He educated her with humanist values and he instructed her—from his relationship with her mother— what sort of love could form a lasting union. From his experiences as a soldier and a doctor, he taught her that war was mankind’s ultimate and most unforgivable evil. And he impressed upon her that human life was sacred.

He taught her to reason and to think. Finally, he taught her integrity to her own values.

Laura then, by age eighteen, had her mother’s beauty and her father’s intellect. There was little surprise when she passed her A-levels, applied to university, scored highly on her entrance examination, and was accepted as one of thirty-six women of a class of more than seven hundred at the University of Bristol. And it was at Bristol that she met Edward Shawcross, the boy whom she quite naturally assumed she would someday marry.

Edward was tall and quiet, wavy-haired, nice-looking, but decidedly tame, and, by Laura’s standards, conservative. They were twenty-one when they met and were both in their final year of university.

Edward was the second son of a wealthy spirits importer in Bristol and had designs of his own to augment the family fortune. He had his eye set at an aging sandstone mansion in the city of Bath, just off the Lansdowne Crescent, which he would buy—here his father was of inestimable help—gut, renovate, and convert into the finest inn and restaurant in the county of Somersetshire. Laura was to be, in a highly glorified manner, the innkeeper’s wife, serving her husband and the Shaw cross & Company brandies, ports, and Sherries.

One day in the spring of 1936, Edward showed Laura the gracious old mansion, his arm neatly tucked around her waist.

“And, of course,” he whispered to her with his usual blend of innocence and lechery, “I wouldn’t mind having our own household staff of five. Maybe three sons and two daughters. But the sons first, of course.”

“Of course,” replied Laura. It was not a totally unappealing proposition. The wealthy hotelier’s wife. There would be money, middle-class respectability, and even a dab of glamour, if the dining room could maintain a high reputation. Life treated many women to much worse. It was just that. . . well, Laura tried to stifle the feeling, but it was all so clear cut. Early on, she entertained the idea that there was slightly something missing. But she fought the idea. There was nothing really wrong with Edward Shawcross and he did not make the difficult physical demands of her that many young men made. Laura also knew that there were several hundred other girls—many of them attractive and from good families—who would claw her out of the way if she did not appreciate him.

It was just that, well, couldn’t life bear her some surprises? Some adventure?

Edward owned a new Alvis “open top.” They spent Saturdays motoring in Devon when the weather permitted. On a day in late May, not long before final examinations, they drove out to Cornwall for a weekend. One of Edward’s aunts owned a cottage near the sea. The aunt was conveniently vacationing in Portugal.

At the cottage, Edward, who was a superior chef already, roasted a rack of lamb, poured unhealthy amounts of his father’s best imported claret, and created a supernal raspberry soufflé for dessert.

Afterward, they lit the log in the fireplace—it was still cool in May—and sipped Beaumes de Venise. Toward ten, Edward placed his hand on her knee.

“Tonight?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said.

They went upstairs, found a large comfortable bed, and virtually fell into it. Laura lost her virginity with surprising ease and no second thoughts at all—the dividend of too much claret, perhaps—and afterward Edward confessed that it was his first time, too. This, Laura had already guessed.

Their scheduled marriage remained unofficial and at least a year away. Laura did not know whether or not she was in love with Edward Shawcross. When pressed, she told him that she was. But was she? She wondered. She knew she had grown to like Edward very much. He was always around. And he was good to her. But was that enough?

Their affair continued. Months passed. She went to a discreet doctor in London, gave her name as Mrs. Vincent Thomas of Basingstoke, and purchased a diaphragm. She thought long and hard about her relationship with Edward Shawcross. Things seemed to be happening too quickly.

Home in Salisbury after graduation, Laura spent much time in the Georgian house in which she had been raised. Mrs. Frasier was long since deceased by now and it was just Laura and her father. Nigel Worthington was proud of the beautiful young woman he had raised. But he was under no illusions about her, a woman’s needs, and Laura’s relationship with Edward.

One night they talked. “I’m expected,” she said ruefully, “to make a decision that will affect the rest of my life. It scares me, Papa.”

“He’s a fine young man,” Nigel Worthington said. “He treats you well. He could offer you a good home and a good life. He bestows love upon you.”

Laura nodded. “But I don’t love him,” she heard herself saying.

“Yes. I know,” her father answered.

Nigel Worthington had a much older brother who had quit school, moved to America years ago, and successfully gone into the steel business in Pennsylvania. The two branches of the family had remained in touch. The English side had the grace, the education, and the culture. The American side had the money and the informality, both in vast quantities. Nigel suggested that his daughter spend the following summer visiting.

There was an exchange of letters. Dr. Worthington had a niece Laura’s age who was finishing university at a strangely named place called Bryn Mawr. The niece, Barbara Worthington, whom Laura had met years ago, wrote that she knew dozens of boys from Yale, Princeton, Williams, and Penn. Barbara promised to give Laura an interesting summer.

“You’ll get yourself involved with some dirty-fingernailed Yank millionaire who does violence with auxiliary verbs,” chided her father. “You’ll love him and never come home.”

“That’s not my type, Papa, actually,” Laura answered.

“But it might be an excellent time for your trip to America, mightn’t it?” her father said. “With what’s going on in the world, who knows how long travel will be safe?”

And if a war starts, she thought to herself, Papa will have me safely tucked away in America, rather than in England, where there could be fighting.

But Laura’s spoken response addressed none of this. “I suspect you’re right,” she said. “About the right time to travel, I mean.”

“The Queen Mary sails every other Thursday for New York,” her father said at length. “What would you think of that?”

Laura said she would think a great deal of that.

One week later, Laura traveled by train to London to book passage. She was met by a man named Peter Whiteside, a longtime friend of her family.

Whiteside was slightly younger than her father. Laura had known that Peter Whiteside and her father had served together during the Great War. Since then, Whiteside had been in and out of the government, mostly in when the Tories were in power, and out when the Liberals held a majority in Parliament. Right now, the Tories were in and so was Whiteside. “Buried somewhere in the Ministry of Defense,” as he himself had put it in March when Laura had seen him last. “But whenever you come to London let me take you to lunch.”

Today was “whenever.”

Whiteside was a tall man, with short hair that was as black as a rook. His face was thinner than the rest of his body, giving an austere, almost gaunt cast to his face. But his eyes were lively and intelligent; they were deep gray and sharp as thorns. He wore a navy suit and his regiment’s necktie. He kissed Laura’s hand when he met her at the railroad platform.

“Laura. I’m charmed as ever. You look ravishing today,” Whiteside said.

Peter Whiteside, she thought, was one of the last of the true English gentlemen, along with her father. The dying breed. The Great War had changed everything in all of Europe. No one made men like this anymore.

“Come,” he said, taking her arm. “We have a reservation at the Ritz dining room for one o’clock. I’ve made an appointment for you at the Cunard offices for the afternoon. I’d like to stop by my office first. Something to discuss.”

“If you’re at all too busy today, Peter,” she offered, “I’ll be in London again before I leave.”

“Nonsense,” he said. They passed through the iron gates of the sooty station. There was a Rolls Royce waiting with a driver. Peter Whiteside ushered Laura toward it. “The ‘something to discuss’ is between us,” he informed her.

“Oh,” she said.

London was best seen from the back of a limousine. Or so Laura decided as the chauffeured automobile pulled away from the curb.

“Now,” Whiteside said at length, “tell me about your impending travels.”

She did. And by the time she had finished, the chauffeur had delivered them in front of a sturdy Edwardian town house, nestled on a quiet tree-lined side street. They were in a residential neighborhood bordering Earl’s Court and Kensington, and Whiteside leaned forward and opened his door. His driver opened Laura’s door and Whiteside ushered her inside, where, upon entering a white rotunda, she began to focus upon the nature of Peter Whiteside’s business.

There was a guard in a suit just inside the door. He nodded curtly as Whiteside entered. Directly in front of them was a portrait of His Majesty, George V, and beyond that, a Union Jack stood in its stand, making its own statement.

Whiteside led her down a short hallway. His office was at the end.

He moved behind a polished rosewood desk and seated himself only after Laura did. He leaned back very slightly in a leather swivel-based chair, steepled his fingers in front of him, and assessed Laura for a final time.

“I think you’ll enjoy America,” he said at length. “Indeed, I suspect you’ll have a wonderful trip.”

She looked back at him, appraising also. “Peter,” she said very firmly, “would you mind telling me why I’m here?”

His fingers broke their token marriage and he returned his hands to his desk.

“No. Not at all,” he said. “Certainly I owe you the explanation, whatever you may ultimately think of it.” Whiteside’s gaze lowered for a moment and he glanced at a pair of papers before him. Then he looked back to her.

“Laura,” he said, “this building belongs to the Ministry of Defense. I work here. They are my employer. I need to know if you would be willing to do something for England. Something which might seem very simple, but which is, in actuality, very important.”

Laura responded with a very stunned silence for several seconds. “You’d better tell me more before I say anything,” she said.

“My child,” Peter Whiteside answered, “as any fool with two eyes could tell you, Europe may soon again be at war. Inevitably, Hitler will draw England in. If this is the case, the intelligence networks which we piece together now—and the information we have access to—may be of vital national interest. Should I go on?”

Laura found herself nodding, and tingling very slightly with excitement.

“This office, the one you are beautifying as we speak, belongs to Military Intelligence 5, the bureau charged with intelligence gathering within the United Kingdom. However, it is part of my duty to coordinate operations with M.I.6, counterintelligence and intelligence gathering abroad. Specifically, operations in the United States and Canada.”

Here Whiteside glanced at his desk again, double-checking the papers before him. “Your trip comes at a very propitious time. And leads you to an excellent place. For our purposes, that is.”

Laura was incredulous. “You want me to become sort of a spy? Against the Americans, is that it?”

Whiteside smiled indulgently. “Not at all,” he said. “Or at least, not exactly.” He pursed his lips against his fingertips again.

He was about to continue when she interrupted. “I thought the Americans were our friends,” Laura said.

“Some of them are,” he answered. “Some of them are not. President Roosevelt is definitely a friend of England. The Vice President, Mr. Jack Garner, the deplorable ‘Cactus Jack,’ definitely is not. But this is precisely the type of thing which we would want you to find out for us. On a lesser scale, of course. One knows all about the American government officials. It’s the people, the important families, we wish to know more about. We need facts, Laura. My office deals in facts.”

“I’m sorry,” Laura said. “I don’t understand.”

Whiteside smiled consolingly. “Laura, dear,” he said, “I’ve known you since you were this high.” One of Whiteside’s hands fled the desk and he held an open palm two feet above the floor. “I would never place you in any danger, you must believe me. But, follow—this office engages in two types of intelligence gathering. What we call ‘white,’ which is the accumulation of information from open sources. Newspapers. Magazines. Conversations with people. And then there is ‘covert’—”

“Which is just what it sounds like,” said Laura, breaking in.

“I would ask you to work for us in the former category,” Whiteside said. “Your situation is absolutely perfect. You are young, beautiful, and single. You will have entrée to the families and situations which we wish to know about. I stress, we are not placing you in any danger. We simply wish to put your eyes, ears, and brain to work for England.”

Several thoughts shot simultaneously through Laura’s mind as she listened: that her earliest memory of Peter Whiteside had been when she was a little girl of approximately five and Peter Whiteside, single, using a cane to brace a hobbling leg, had come along on a trip to Scotland with the Worthington family. That from what she knew about such things, Whiteside must carry a reasonable bit of authority within the M.I. 5 or 6 and that he made his own recruitments. That the rumors that always circulated about flirtatious Peter were probably true — he did like boys and girls. And that he was here now in front of her, poised like a spider in his own web, trying to recruit her to work for him.

“So I’m to be a spy,” she said in mounting wonder. “Is that it?”

His eyes danced in an absurdly young way.

“Hitler has spies,” he said with a flicker of a grin. “England gathers intelligence in the interests of her own defense. When were you thinking of sailing?” he asked.

“June the fifth,” she said.

Whiteside glanced to a calendar on his wall. Her eyes followed his and she saw the bold figures 1937. “That would be excellent,” he said.