in Mystery, Thriller & Suspense…

and 115 rave reviews!

darkly funny…about haves and have-nots, takers and givers…smart and savvy…”

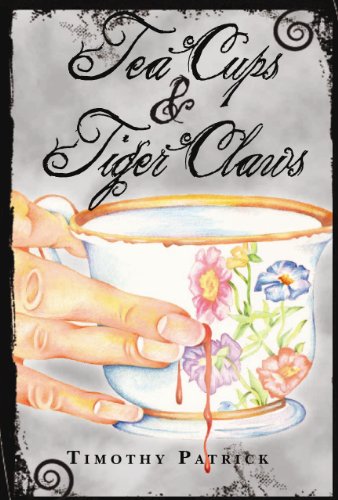

Tea Cups & Tiger Claws

by Timothy Patrick

First comes the miracle and then comes the madness. The miracle is the birth of identical triplets, and the madness is all about money, of course. The year is 1916 and the rare occurrence of identical triplets turns the newborn baby girls into pint-size celebrities. Unfortunately, this small portion of fame soon leads to a much larger portion of greed, and the triplets are split up—parceled out to the highest bidders. Two of the girls go to live in a hilltop mansion. The third girl isn’t so lucky. She ends up with a shady family that lives in an abandoned work camp. That’s how their lives begin: two on top, one on the bottom, and all three in the same small town.

Identical in appearance and with the same blood in their veins, the sisters should have also shared united destinies. Instead, those destinies are thrown to the wind, and the consequences will be extreme. Tea Cups & Tiger Claws explores wealth and poverty, jealousy and conceit, and is ultimately a story about deadly ambition and how it will once again throw the sisters together. It’s a journey that spans fifty years, three generations, and the perilous gulf between the rich and the poor. Along the way, you’ll marvel at the opulence of a mansion where presidents are entertained, and you’ll walk cautiously through a shanty town that harbors the forgotten. So get ready for the unexpected, and let “Tea Cups & Tiger Claws” take you down the crooked byways of this captivating family saga.

5-star praise for Tea Cups & Tiger Claws:

“A truly wild ride…a page-turning, can’t put down tale…”

an excerpt from

Tea Cups & Tiger Claws

by Timothy Patrick

Chapter 1

It started in 1916 when the newspapermen came to town to write stories about a local scamp who’d given birth to identical triplets. Truthfully, the whole thing didn’t look like much more than a new swatch on an old quilt, but they came anyway. Maybe it had something to do with all the gloomy headlines: German Zeppelins Bomb Paris; Summer Olympics Canceled; Special Dispatch From The Trenches Of World War. Gloom doesn’t sell. That’s what the newspapermen said. Scandal and depravity sell, and if those commodities can’t be found, out comes the human interest rainbow slapped across the dreary landscape of the front page. In this case the rainbow took the form of sixteen-year-old Ermel Sue Railer and her three baby girls. Her cornpone husband, Jeb, told wild stories and took a good picture, as did Ermel—when she covered her buck teeth—and her birthing of the first identical triplets born in the U.S. in over a year made for a story that promised to sell at least a few newspapers and magazines. Reporters, photographers, and sketch artists hopped into the town of Prospect Park, California like penguins at breeding time.

Of course the Town Council didn’t care for any of this. The fact that Jeb and Ermel lived there at all made the town look bad enough. Now the whole world knew about them and about their ratty home down on Pine Street. They lived in a development named Yucatan Downs, derisively known as Yucky D, which consisted of two-bedroom shacks surrounding a dirty courtyard where chickens, dogs, and neglected children scurried amongst broken down wagons and a couple of precariously leaning outhouses. The place had originally been a work camp, thrown up years earlier to temporarily house the carpenters who’d built the first mansions on the hill, but instead of getting torn down, a clever speculator slapped on the exotic name and filled it full of undesirables.

Other than the disgrace of having Prospect Park’s good name lumped in with the likes of Jeb and Ermel Railer, the articles in faraway magazines and newspapers didn’t cause any real damage; readers of the New York Times Sunday Magazine might’ve been captivated by the miracle of identical triplets but they didn’t hop a train to come see for themselves. In neighboring cities they did. Cooing, gushing baby lovers from miles around invaded Prospect Park and clogged the downtown streets with wagons and noisy mules. They chugged up the hill in smoky model T’s to ogle the mansions. They guffawed and said howdy and showered the town with the lowbrow familiarity of a bean picker on pay day.

Despite these aggravations, the good people of Prospect Park weathered the storm with their usual dignity. These things needed to be kept in perspective. The city of Santa Marcela had been plagued for decades by a whole colony of Railers. Prospect Park, on the other hand, had one little nest. All things considered, the good people seemed to be fortunate.

~~~

Ermel didn’t mind the steady stream of tearful women who took turns hovering over the bassinets, especially when they tucked quarters and half dollars into her hand. And when she sat for the artists, surrounded by babies, she kept an eye on Jeb to make sure he didn’t pocket any of the envelopes that some of the rich folks left behind. Along with the usual Bible tract, these envelopes often contained folding money of ones, fives, and even tens; folding money that soon put her into a lavender hobble skirt and shirtwaist and lace up boots. All in all, Ermel Railer found motherhood to her liking.

One afternoon two weeks after the birth, after the hubbub had died down, when sleepless nights and boiled diapers began introducing Ermel to a world of motherhood that didn’t include little envelopes filled with cash, a stern looking man with perfectly oiled gray hair knocked on the door. He wore a chauffeur’s uniform, and Ermel easily pegged him for just another uppity servant.

“The duchess wishes to see the babies,” he said, slowly and precisely, like someone who wants to be understood so he doesn’t have to be around any longer than necessary.

“Then tell her to come in,” said Ermel.

“She has instructed that the babies are to be brought to her in the motorcar one at a time, ten minutes each.”

Ermel’s toothless mother, Gurty, who’d moved in to lend a hand, laughed contemptuously from the bedroom.

“You tell Princess What’s-Her-Name,” said Ermel, “that this ain’t no café, and she can’t order up my babies like a plate of pork chops.”

He stared scornfully. Then he took a small envelope from his vest pocket and handed it to her.

“Wait here,” grumbled Ermel, as she hurried to the bedroom that she and Jeb shared with the babies.

“How much she give?” asked Gurty.

“Ten dollars.”

“She better.”

Ermel flung off the dress she’d been wearing and put on the new hobble skirt and shirtwaist. From a shiny red box she then lifted a giant hat with a wide brim and peacock feathers jutting out the back. She carefully put on the hat and tucked a few loose strands of black hair behind her ear. Then, after tracing red lipstick across her mouth, she admired herself in the mirror. Nobody showed up Ermel Railer, not even a duchess. She walked confidently to the front door.

“Mrs. Railer, you seem to be forgetting something,” said the man.

Ermel looked down at her outfit and said, “No, I got everything.”

“The baby, Mrs. Railer.”

“Oh yes. How silly of me.”

When Ermel saw the long, gray motorcar parked on the street, she placed the name: the Duchess of Sarlione, who used to be Jeannie Brynmar before she got herself a royal title by marrying a penniless Italian duke. A few of the local heiresses had gotten titles like that, but this one stood out because she came back from Europe with the title—for a price—but not the duke, and because she wrapped herself in pure white ermine and rode around town in a Rolls Royce Silver Ghost.

“You are to address the duchess as ‘Your Grace.’ Do you understand?” said the chauffeur as they approached the car.

“I think I know how to greet my visitors thank you.”

After opening the motorcar’s back door, the chauffeur said, “Your Grace, this is Mrs. Railer.”

“Hello Mrs. Railer.”

Ermel looked in and saw a picture right out of McCalls. The big brown eyes, perfect white skin, glossy red lips, and stylishly short hair looked like they belonged to an expensive porcelain doll that people like Ermel didn’t dare touch. Then her natural defiance kicked in and she said, “Hello lady. I like your motorcar. Might get one myself…now that I’m in the magazines and all.”

“This must be your baby daughter…one of them anyway,” said the duchess with a small, sad laugh. “Please get in.” She reached out and pulled down a jump seat. Ermel tried to step up to the running board but got hobbled by her hobble skirt, so she hiked it above her knees, and climbed in, baby and all, hitting her hat on the convertible top and knocking it catawampus across her head. She finally wiggled into the seat, which faced the duchess, and self-consciously put herself back together. The chauffeur closed the door.

“Can I hold her?”

“You paid your money didn’t you? Sure you can hold her.”

The duchess bit her lip and took the baby. She had tears in her eyes. The lady who had fur coats and servants and a motorcar that cost more than a house, cried over a baby.

“What’s her name?”

“Uh…uh…Abigail.”

“Hello Abigail.”

For the next ten minutes the duchess touched the baby, smelled the baby, hugged the baby, and rocked the baby. She did everything except change the baby’s diaper. And every time the baby made a goo-goo sound, she rejoiced as if the kid had just graduated medical school. Ermel alternated between eyeballing the Rolls Royce, the ermine coat, and the duchess, who seemed to be off her nut.

As she handed back the baby, a leg popped through the swaddling blanket. Unable to resist, the duchess grabbed the little foot and pressed it to her face. Then she noticed a tag tied to the ankle. She looked at it and then looked at Ermel. “It says Judith,” she said.

“Then it must be Judith.”

The duchess kept staring.

“We swap names all the time. They don’t know no better. Except for Dorthea. We don’t swap her name on account of her pale blue eyes.”

“Pale blue eyes? Aren’t they identical triplets?”

“Yeah…I’m not sure how all that stuff works. They all got blue eyes but Dorthea’s are kinda like steel blue. The doctor says she got an infection that caused her eyes to come out different than the others.”

“But she can see…there isn’t anything wrong with her eyesight, is there?”

“Nah, there ain’t nothing wrong…except if you stare at ‘em too long it kinda puts you in a trance.”

“Really! Bring me Dorthea next!”

As Ermel walked back to the house to exchange one baby for another, she saw her next door neighbor, Mrs. Krawiec, staring out her window. And in the next house over she saw Mrs. Duda, and her teenage daughter Aniela, staring out their window. Ermel looked back over her shoulder, across the street. Even there, in the normal houses, she saw eyes glued to windows, and she realized none of them had ever said two words to a real live duchess or sat in a duchess’s Rolls Royce. Ermel walked proudly back to her house.

Later, after Jeb came home from a night of spending the contents of one of the envelopes, she told him about the duchess. Of course he blew his top. “Our babies are good enough for her to slobber over, and you’re good enough for her to order around like a slave, but our house ain’t good enough for her highness to step foot into?” Nobody blustered better than Jeb Railer. He badmouthed the people on the hill in general, and cussed one family in particular: the Newfields. That’s what Ermel liked about him. That’s why she married him. And because of his handsome face…and she got pregnant.

So Jeb ranted and raved and made her promise to stick it to the duchess if she came around again. When Ermel showed Jeb the envelope, he calmed down and fell asleep grumbling.

The duchess did come around again—two days in a row. On the first of those days everything went as before: the uppity chauffeur knocked, Gurty sneered, Ermel carted babies back and forth, and the neighbors got bug-eyed. The next day, though, things changed.

“Hello Mrs. Railer,” said the duchess. “It’s me again. I hope you don’t mind another visit.”

Ermel tried to look put out as she climbed into the motorcar.

The duchess held out something in her hand and said, “I brought you a little present.”

The two ladies exchanged bundles. The duchess went to mush over the squirming one and Ermel expectantly unfolded the other.

“It’s a satin and chiffon evening dress,” said the duchess, between fits of adult baby talk. “I think it will look great on you. It’s by Lucile.”

“Oh…yes…Lucile,” said Ermel.

She gently stroked the silky material. The duchess gently stroked the baby’s downy head. Ermel pressed the cool satin to her face. The duchess pressed the baby’s pure face to hers. Ermel hugged the dress. The duchess hugged the baby.

Thanks in no small part to Ermel waiving the dress around like a crazy flagman as she walked back to the house, this time the neighbors didn’t try to control themselves. They came poking around before the big car’s smoky exhaust even had a chance to clear. The two Polack ladies, Krawiec and Duda, pretended to be just passing by but quickly small-talked their way into Ermel’s house. Vera Snyder, the white trash from across the courtyard who stole clothes pins from the neighbors, came in looking for a match to light her cigarette, which the Polacks thought scandalous, but not enough to make them leave. A Mrs. Barnes, from across the street, who’d never said boo to anyone at Yucky D, came over with a gift. Ermel tossed it onto the bed and concentrated on getting into the new dress.

The visitors surrounded the bassinets, paid their respects to the babies, and then followed like hound dogs when Ermel sashayed into the kitchen wearing the black and white dress. She stopped next to Gurty, who sat at the kitchen table, and held a sleeve out to her visitors. “It’s a gift from the duchess,” she said. “You may touch it if you want.” The Polack ladies wiped their hands on their aprons and held their breaths as they ran the shiny fabric between their sausage fingers. “It’s satin. Made from silk,” explained Ermel. “And looky here at the bow. It feels like velvet.” Mrs. Barnes, too dignified to fawn but too curious to abstain, touched the fabric also. Only Vera, who loudly puffed a cigarette in the back, ignored the offer.

“It’s by Lucile,” said Ermel.

“Oh yes. Lucile,” said Mrs. Barnes. Mrs. Krawiec looked confused and whispered into Mrs. Duda’s ear. She got a jab in the ribs by way of a response.

Ermel had never commanded such attention in her short and unspectacular life. She withdrew the sleeve and watched everyone’s eyes follow the simple movement with rapturous attention. She danced around the kitchen like a ballerina, watching their facial expressions rise and fall with every bend of the knee. She watched as they hypnotically shuffled toward her like moths to the fire, following, turning, inching closer, until they had her deliciously cornered.

From the table, Gurty coughed up a chuckle, but no one else made a peep. The Polack ladies didn’t want to barge forward when Mrs. Barnes, their social better, might want the privilege. Vera seemed content to look on like a hungry spider. Finally Ermel said, “Are you just gonna stand there staring or are you gonna talk?” And then the flood gates opened. “What does the duchess sound like?” “Does she have an accent?” “What do you talk about?” “Does she like kielbasa?” “What type of perfume does she wear?” “Does she like dumplings?” “Where’s the duke?” “Does she have a villa in Italy?” Ermel answered all the questions in a manner befitting the owner of an evening dress by Lucile.

And then Vera Snyder spoke. “Ya know why she keeps coming around, don’t ya?”

“I think she wants me to be her friend…since I’m famous and all.”

“She wants your babies. That’s what she wants,” said Vera.

The other ladies gasped.

“Don’t be stupid,” said Ermel.

“How many people have come two days in a row?” asked Vera.

“I don’t know. A few.”

“And how many have come three days in a row?”

“I got better things to do than count my visitors, in case you ain’t noticed.”

“None. That’s how many. I seen every buggy and motorcar that come through here.”

“That don’t prove nothin’. If she ain’t my friend, how come she give me this deluxe dress?”

“Because she knows it’ll unscrew your head, and you’ll start dancin’ around like a fool instead of keeping track of your babies.”

“You’re just jealous ‘cause my best friend is a duchess.”

“If she’s such a friend, how come she don’t never come in your house?”

The other ladies acknowledged Vera’s point with a quiet murmur. Ermel looked at her feet. “I’ll bet you five dollars,” continued Vera, “she won’t never come in here ‘till the day she takes your babies.” She reached over Gurty’s shoulder, snuffed out her cigarette in the ashtray on the table, and walked away. “Let me know,” she said as she swung open the front door, “I could use the money.”

Nobody showed up Ermel Railer, especially not the likes of Vera Snyder. The next day, when the chauffeur once again knocked upon her door, Ermel locked Gurty, who wasn’t fit for company, in her bedroom and went out to invite the duchess in to see the babies. She said they were sleeping and couldn’t be brought to the motorcar. The duchess politely declined and drove off. Still determined, Ermel went out that very day and bought teacups and a lace table cloth and pastries from the fancy bakery on Center Street. This finery proved to be no temptation whatsoever to the duchess. After the third try, when Ermel pushed too hard, the duchess stopped coming altogether.

Ermel knew envy. She knew the choking kind that turns its victim into a big talker who bristles and puffs but still goes to bed feeling small. She had no taste for hope or contentment or thankfulness, so she slurped a resentful gruel that numbed her heart and leached her soul. Yes, Ermel knew envy like a prisoner knows handcuffs, but for a few blessed days she’d felt the freedom of handcuffs removed when she, Ermel Railer, had been the big somebody; when the fawning, licking eyes had been glued to her instead of the other way around. She’d been the one with the duchess, and the dress, dishing out jealousy and serving up discontent like a flashy soda jerk. And she liked it, loved it, and now that it was gone, she felt devastated. Ermel fell hard off her pedestal and landed right back where she’d started: envious and small.

Fortunately, she’d married into a family that had been producing champion enviers for a century. In her hour of need, when she had the bile, but not the throat to deliver it, her husband stepped in to pick up the slack.

“You know what’s the difference between them hoity-toitys up on the hill and us down here? I’m asking you! Do you know?” hollered Jeb. “They’re better cheaters and liars! That’s it. And that duchess lady is worse than most ‘cause she went out and got herself an extra coat of paint to cover up her cheatin’ and lyin’. That’s what her title is, a cover up!”

And then he howled about the Newfields, calling them the biggest cheaters and liars of all.

“And if she’s a real duchess then I’m the King of Siam and my ass is Prince Charming! Anybody can get a title—it ain’t no harder than puttin’ down your name on a legal document—but most people don’t do it ‘cause they know it ain’t right. Why do you think nobody ain’t never seen the duke? ‘Cause he don’t exist, that’s why!”

And then he wailed about the hatchet job done to his family name and how no royal title on earth could repair it.

“And that motorcar ain’t hers neither. My friend up at the tannery told me so. It belongs to a motorcar salesman in Santa Marcela. She drives it during the day and he drives her at night, if you know what I mean.”

And then he drove himself crazy talking about the Newfields.

Jeb did a proper job on the duchess and made Ermel proud. Of course he got something out of the deal too. Up at the Wagon Wheel Tavern nobody listened to his stories anymore, unless he bought them a drink. Now he had someone who did it for free. As long as he took a break every now and then to commiserate with Ermel and complain about the stuck up duchess, she let him pontificate as he pleased. For a while she even laughed in the right spots, thought of cuss words when he ran low, and clucked her tongue when the shame of the Newfields called for it. That’s how it went for three days running, like it used to be before they got married, almost blissful.

Too bad Ermel’s hour of need didn’t last a week, maybe the bliss could’ve taken root, but she had a house full of babies and needed to figure things out, like how to pile as much work as possible onto Gurty without killing her. Besides, what good ever came out of Jeb’s tired old stories? They sounded daring, but he never got anything out of them, and now, after three days, all Ermel got was a headache. So she stopped listening, and Jeb went searching for an audience back up at the Wagon Wheel Tavern. Ermel could live with that. It was a routine she knew—even though they’d only been married seven months. He’d drink and argue and try to make loud speeches. He might get kicked out and have to try his luck at the bar across the street, or he might make it to closing time. After midnight he’d stagger home, barge in like a hurricane, and make another speech. And then the next day he’d do it all over again, unless the money ran out, in which case he’d go to his uncle’s in Santa Marcela to make a few bucks.

But this time it didn’t happen like that. This time Jeb came home earlier than usual and slipped through the front door like a cool summer breeze. Humming a happy tune, he moseyed up to the table where Ermel and Gurty had just started dinner, reached into his overall pocket, and pulled out a bottle of store-bought gin. He put it on the table with a wink. Ermel liked store-bought gin but usually got stuck with the rotgut sour mash from Jeb’s uncle.

“What’s the occasion?” she asked.

Jeb stared at her, started to say something, stared some more, and then said, “We’re celebrating our good fortune.” He swung his leg over a chair and sat down.

“If you’re talking about the money in the envelopes, there ain’t nothing to celebrate ‘cause you’ve spent every last dollar of it.”

“I ain’t talking about that. I’m talking about true good fortune, the good fortune of powerful friends in powerful places.”

“And what friend might that be?” asked Ermel suspiciously.

With raised eyebrows and a knowing smile, Jeb said, “We shall see.” He put a big piece of cornbread on a plate, covered it with sausage gravy, and picked up a fork.

“We shall see is right,” said Ermel, as she snatched away his plate. “What friend are you talking about?”

“The one that got me a job that pays ten dollars a day.”

“Ten dollars? For doin’ what?”

“Drivin’ a truck half day.”

“Some drunk in a bar says he’ll pay ten dollars for a half day’s work and you believe him?” snorted Ermel, followed by a bigger snort from Gurty.

Jeb tossed an envelope onto the table and said, “That’s for the first two weeks. Paid in advance. Cash.” He grabbed the plate from Ermel and dug in.

Gurty reached for the envelope, but Ermel beat her to it. After a quick count, she said, “There’s a hundred dollars in here!”

“Just like I told you.”

“What are you gonna to do with it?”

“I’ll tell you what I’m gonna do. You’re goin’ up town tomorrow and spend every penny on yourself. You’re gonna buy jewelry and perfume and all the other whatnots. And when you run out of things to buy in Prospect Park, I’m takin’ you over to Santa Marcela.”

“Really?”

“It’s a celebration, ain’t it?”

With brown gravy dribbling down his chin, he smiled and chewed enthusiastically.

After dinner, Gurty ran from one fussy baby to another while Jeb and Ermel sat at the kitchen table and downed big glasses of gin-lemonade. When that ran out, they poured rotgut whisky and talked loudly about the big motorcar they’d buy, and the big house—maybe even a big house at the base of the hill. Why not? It’d been done before. After all, they were the famous Railers who owned the newest set of identical triplets in the country, maybe even the world.

While Ermel might’ve been a simple, dirt-poor sixteen year-old, she possessed the suspicious nature of a purse-clutching old lady. Gin-lemonade and rotgut whisky applied to an unsuspicious mind can smooth the jagged edges of apprehension down to harmless nubs. On a mind like Ermel’s, it didn’t work. Even at the height of their boisterous revelry, when numb lips impaired speech and floating brains turned rational thoughts into bobbing apples, those jagged edges called out to her. Why had Jeb forked over the money? He never did that. The rent got paid only when the landlord parked his motorcar outside their front door and caught Jeb off guard. Ermel kept food on the table only because she foraged his overalls for loose change and the odd dollar. Now he was tossing around packets of money and telling her to spend it all on herself. And who was this powerful friend that passed out high paying jobs to the likes of Jeb Railer? Too many jagged edges.

In her quest against these suspicious happenings, Ermel had a secret weapon: Jeb’s big mouth. He knew how to talk, and more often than not, talked himself into trouble. She just needed to wait.

And sure enough, after a while his head tipped to the side, and the words started running wild. He raised his glass and hollered, “Here’s to the duchess! I take back half the stuff I never said about her!”

Ermel put the brakes on her spinning head.

“It just goes to show you can’t judge a cook by its cover…a cook by its…a…you know what I mean,” he said.

“What are you saying, Jeb?”

“I’m…er…saying what I’m saying. What do you think I’m saying?”

“Jeb, what are you saying about the duchess?”

“Oh yeah, the duchess. She must want kids real bad.”

Ermel sat up straight and said, “You better not be talking about my kids, Jeb Railer.”

He tried to likewise straighten himself up and meet her glare. “Well maybe I am, and maybe I ain’t.” He leaned forward and studied her face. “Your mouth is wadded up like a horse’s butthole. That means you’re mad. But I got a secret that will make you happy…and then the horse’s butt will go away. Come here and I’ll tell you…but you can’t tell no one ‘cause the man said so. Come here.” She leaned in close and he said, “We’re gettin’ three thousand dollars for ‘em.” And then he sat back and beamed like a man with a gold mine.

The horse’s butt didn’t go away.

“You snivelin’ son of a bitch! You sold my babies to that…that two faced, stuck-up duchess!”

~~~

Nobody ever accused Jeb of having any sort of a military bearing, but on the night when Ermel figured out his little scheme, he would’ve made a terrific soldier. With his wife bearing down like a frothing charger, instead of indulging his appetite for drunken combat, he fortified his wobbly legs with sheer gumption and quickly affected a strategic retreat. He saved himself. He saved the day. He saved the cause. Then again, maybe it hadn’t been anything quite so noble. Maybe it had been the power of money. Like a rat following its nose to the dumpster, maybe the smell of money raised Jeb up and safely guided him through the alcoholic fog and away from his raging wife. It didn’t matter though because it ended with the same results: he had indeed saved the cause and would fight again.

And lose repeatedly.

First, when Ermel had calmed enough for Jeb to risk proximity, he attacked with love. With a bowed head and a lump in his throat, he offered up his own tender heart to be cracked like a melon. Didn’t his little girls deserve the best? Didn’t they deserve fancy dresses and shiny leather shoes and nannies and maids and…and…banjo lessons and all the other whatnots that went part and parcel with being rich? Yes they did, and he’d be a darned sorry father if he didn’t give it to them. Yes, it was true he’d never recover from the loss, but he had to do it because he loved them that much, and, he knew, Ermel loved them that much too. They had to let their babies go to the duchess.

This argument didn’t go anywhere, but it seemed like a good place to start.

Next he tried greed. Everyone is greedy. It’s like hair, everyone has it to some extent, and Ermel’s endowment fell on the bushy side of the scale. Besides the money from the new job, he’d agreed to a thousand dollars for each baby. Now the lawyer, a serious, frowning man named Mortimer Pugh, said buying and selling babies went against the law so the thousand dollars had to be what he called a “one time re-imbursement of expenses material to the birth and sustenance of each adoptee up to the point of adoption.” Let him call it what he wanted, it still added up to three thousand dollars. Jeb begged Ermel to think about all the things she might do with that kind of money. Responding with a hateful glare and the brevity of a corpse, she told him she’d never sell to the duchess. Jeb pressed on, dangling the dream house in her face, the dream house at the base of the hill that three thousand dollars might just buy, the dream house that might just turn her into a lady…unless, of course, she liked being white trash. Ermel threw a plate at his head.

Jeb threatened and screamed. He put a big dent in the wash tub and almost broke his foot. Each and every time Ermel stared him down and backed him out of the house, where he trudged up to the Wagon Wheel to convalesce, or sometimes strategize with Mortimer Pugh.

Only a few lousy signatures stood between Jeb Railer and more money than he’d seen in a lifetime. A few squiggles of ink. That’s it. It’s one thing when the money sits in a vault underground, or behind the cold stare of armed guards, but when your own spiteful wife is the one slamming the door in your face, that’s more than a man can take. He’d have been the first to admit the sinfulness of it, but murder even crossed his mind, or at least a sturdy coma. He also thought about forgery, but didn’t see a way past Pugh, who said things had to be done up proper.

But what about lying? Husbands lie to their wives on occasion. They have to, unless they like walking around in an apron. Wives think faster and scheme better, so husbands lie. It levels the playing field. So Jeb changed his strategy.

“It’s too bad,” he said one day, with a sigh, “‘cause I guess the duchess really did like you after all.” Maybe Ermel told him to shut up, maybe she didn’t. Jeb concentrated on dangling the worm and didn’t really care. The fish won’t bite if it doesn’t see the worm. “I’m to blame more than anyone I suppose, the way I turned you against her, but how was I to know she wasn’t a phony like all the rest?”

She ignored him.

“Yep. I done wrong and knew it for certain today when I give the lawyer your answer. Instead of getting mad, he said it was a shame things didn’t work out ‘cause the duchess missed her get-togethers with you and wanted to invite you up to her mansion for tea—after all the adoption business got settled.”

“You’re a liar Jeb Railer,” said Ermel.

And then a faint smile crept across her mouth, and she tilted her head almost imperceptibly to the side. She’d seen the worm.

“That’s probably why she give you the dress…to get you started with all that fashion stuff—so’s you fit in with the ladies on the hill.”

No response.

“Wouldn’t that be somethin’? Picked up for tea with the duchess in that fancy motorcar and delivered up the hill in style? I can see the smoke comin’ outta Vera Snyder’s ears right now.”

“It ain’t gonna work, Jeb.”

“What are you talkin’ about?”

“You know what I’m talkin’ about.”

“I’m just makin’ conversation. Last I heard that weren’t no sin.”

“Well you can just give it up.”

“Fine.”

“Fine.”

“Fine….But it ain’t a hard thing to prove. All you gotta do is ask the lawyer. Do you got somethin’ against that?”

No response.

“You should ask him. The duchess said every word I just told you, and he’ll tell you himself—and them fellas ain’t allowed to lie or they get what you call de-burred.”

“De-burred. You don’t know what you’re talkin’ about…. What else did he say—not that I believe a word of it?”

“Nothin’. The duchess likes you and wants to invite you to a tea party. That’s it.”

“Jeb Railer you won’t get away with it if you’re lyin’ to me! You know that don’t you?”

Jeb did get away with it, at least long enough to get Mortimer Pugh into his house, up to his kitchen table, and sitting face to face with Ermel. And it turned out the lawyer knew a thing or two about lying himself, hard as it is to believe, given his noble profession and all.

A bad liar presses too hard and spit-shines the lie until it blinds. A good one throws it out like yesterday’s news and shrugs at the wonder of it. A bad liar hovers over a syrupy-sweet concoction of impossible dreams. A good one boils the dream in a sludge of boredom or contempt or, in Mortimer Pugh’s case, frustration. He bemoaned the time wasted by the duchess planning a tea party when she had important business matters to tend to. Then he asked forgiveness for speaking out of turn. When pressed on the issue by Jeb, on account of his wife’s unbelief, the lawyer made a show of irritation as he dug around in his leather bag and produced a personal invitation from the duchess. He handed it to Ermel and then drummed his fingers and looked impatiently at his pocket watch. Ermel tugged on the lavender ribbon that bound the folded, cream-colored card. Inside, she read:

The Duchess of Sarlione wishes to extend her cordial invitation to a tea party on Monday, the second of October at one o’clock in the afternoon at Toomington Hall. RSVP Toomington Hall.

“It ain’t no good. The second of October has come and gone,” said Ermel.

“Yes, it’s my understanding that the duchess had expected a speedy arrangement with you—based upon your friendship—after which I was to present this invitation. Unfortunately the arrangements have not been speedy.”

“Is she plannin’ another one?”

“It’s my understanding that she thinks of nothing else.”

Jeb watched the smile creep across Ermel’s face.

“Er…Mrs. Railer, may I have the invitation back please, as it is expired…and no doubt the duchess has a new one for you…provided there are no further delays.”

The next day a motorcar picked up Jeb and Ermel and drove them to Mortimer Pugh’s office in Santa Marcela where they sat in high-back leather chairs around a giant table and signed papers. A notary sat at the end, ramrod straight, and clicked his teeth twice each time he placed a new page on his stack of papers. He acted finicky and precise, like a champion librarian.

After two of the three sets of documents had been signed, Ermel excused herself to the powder room. The men stood as she left and then sat back down with smiles all around. Everything looked good. The lawyer had tamed the wild pony without her even knowing it; the notary proudly hovered over his parchment kingdom; and Jeb had a pile of money coming his way. One more little push and it would be over. They leaned back in their executive chairs and waited. But Ermel didn’t come back. Not after five minutes. Not after fifteen. Jeb went to investigate. Through a locked door she told him to go back and wait. “And keep your mouth shut,” she added. Not wanting to raise her ire at this critical juncture, he meekly followed orders. After thirty minutes the notary started processing the documents that had already been signed, which took about five minutes, and then said he had to go. Pugh talked him back into his seat with a promise of future business and a direct order for Jeb to go get his wife, even if he had to drag her back to the meeting. Jeb knew better than that, so he begged instead.

“Is everybody good and mad?” asked Ermel.

“Yes.”

“Mad enough to quit the whole thing?”

“Yes.”

“Good. Now go back and keep your mouth shut.”

When Jeb returned empty handed, the notary packed his bag and announced his departure, future business or no future business. That’s when Ermel entered the room, looking innocent and refreshed. And what did they say? Nothing. She’d been in the powder room, and they were men who knew better than to talk about such things. So they picked up where they left off, this time without the smiles. The notary clicked his teeth faster than ever, slapped each page down with barely a glance, and in five minutes had the job done.

Now the time had come to arrange handing over the babies, a topic Ermel had been cleverly avoiding. Jeb knew she didn’t mind giving up a few signatures, but she’d never give up anything that mattered until she got something in return, something more than fancy words and an old invitation to a tea party. What she didn’t understand, though, was that the duchess had already been to court, and the adoption had been set. All that remained was what Pugh called, “a properly executed Consent to Adopt,” the same Consent to Adopt that Ermel had just signed. She didn’t have a bargaining chip. She had someone else’s property and it couldn’t be bargained with at all. She’d signed over the babies and nothing but a knock on the door kept her from knowing it.

Of course Mortimer Pugh had a dozen different ways to take the babies from Ermel. A phone call to the sheriff, a mention of his client’s name, and he could have the babies tucked away at Toomington Hall by that very afternoon. But since Pugh didn’t want to make a nasty scene at Yucky D that might cost him business on the hill, he insisted on playing Ermel for one more round.

After the notary left, the lawyer made his horseshoe frown look something like a smile and said, “Now let’s turn to more pleasant matters. The duchess is hoping that you’ll deliver the babies yourself, Mrs. Railer, that way she can personally deliver your invitation to the tea party—a tea party, I might add, which is being given in your honor, and will be attended by only the best people from the hill. You are very fortunate, I must say, to have made such a friend as the duchess. Shall we say day after tomorrow then? Of course she’ll send her motorcar for you. Is that agreeable?”

~~~

Ermel had less than two days to get ready for the biggest day of her life. She spent a good part of that time telling her story up and down Pine Street. She didn’t doubt that some of the neighbors might turn out to see her off, maybe even wave their hankies as she drove by. She also tried putting a shine on Jeb’s social graces but eventually realized two days wasn’t long enough—or two years—so she made him promise not to pick his teeth with a pocketknife or say the word “reckon.” She also did some shopping for a particular item.

On the appointed day, at the appointed hour in the afternoon, Ermel watched out the window as the gleaming Rolls Royce pulled up to Yucky D, not just to the street in front, but into the actual courtyard, next to the outhouses. It’s safe to say this had never happened before. The Chauffer, just as starched as before, knocked on the door, announced his presence, and offered to be of service. Ermel put him to work loading bags and travel bassinets into the motorcar. After this he held open the motorcar door as Jeb approached wearing a top hat and tails and britches that needed lengthening. Not used to the duds or the motorcar, it took some doing getting him loaded into the back seat.

And now the moment had arrived. Ermel emerged. Actually the bow of her giant hat appeared first, jutting through the doorway like an ocean liner cresting a wave. But sure enough, there was Ermel too, underneath the ocean liner. She struck a pose of dignity and substance and strolled solemnly toward the Rolls Royce. A cry of “yoo-hoo, yoo-hoo” interrupted the silent procession. The Polack ladies, locked arm in arm on a nearby porch, called and waved to her. Ermel stopped, looked at them as if she’d never made their acquaintance, and nodded her head oh so slightly. Then, in case they’d missed it, she stroked the white ermine stole that draped her shoulders, the special item she’d bought for herself. It had taken a fifty dollar down payment and a six month payment plan, but she had to have it because in her new world a lady needed more than fancy hats and high button boots. She looked across the courtyard at Vera Snyder’s house and saw the curtain move. Across the street she didn’t see any well-wishers but saw plenty of eyes glued to windows. With a quick look back at Vera Snyder’s, she caught her staring like all the rest. Poor, unfortunate little people, too jealous to come out and send her off properly. With a hand extended to the chauffer, she slid into her seat with impeccable grace.

At Ermel’s command, the Rolls took a lengthy, circuitous route to the base of the hill, giving her many pleasant opportunities to get stared at by people on the street. It would have been more pleasant had she been able to watch them stare, but that didn’t seem right, so she captured as much of their envy as possible by looking out the sides of her eyes and stealing occasional glances.

And then the motorcar turned left on Center Street and started climbing the hill.

Ermel watched manicured hedges and expansive lawns sail past her window, and the higher the motorcar climbed, the more manicured and expansive they became. She saw long driveways at the base of the hill give way to long, meandering driveways, which gave way to driveways that meandered farther than the eye could see. She counted chimneys. Three chimneys, three chimneys, three chimneys, four, five chimneys, five chimneys, five chimneys, more. Her eyes rolled from rooftop to rooftop, hopscotching across the tops of the modest mansions, frolicking at length across the tops of the fairyland estates. And then the motorcar stopped in front of a giant wrought iron gate. They had arrived at Toomington Hall. The top of the hill. Almost the very top.

Next to Sunny Slope Manor, Toomington Hall was the most famous mansion on the hill. Only those two sat on the north side of Sunrise Way, with Sunny Slope crowning the top, and Toomington off to the side. Every other house in town sat below, like servants. Toomington also shared a Queen Anne architectural style with its fancy neighbor, a fact which the Chamber of Commerce trumpeted in their brochure: “When gazing to the top of our fair town, you will be inspired not by flat-roofed moderns that mingle politely with the mountainside, but by two majestic Victorians towering audaciously and piercing the blue sky with their razor sharp peaks.”

An old man in a blue uniform came out of the gate house, nodded to the chauffer, and pulled on a metal bar sticking out of the ground. From inside the gatehouse came a loud clank and a buzzing, whirring sound. The giant gate started opening. In the middle it had a fancy brass plaque with the letter “T” on it. Ermel’s eyes followed the brass plaque as it moved from right to left. Then the engine revved and the motorcar began the final climb to the top.

Jeb stared out the window with an open mouth. Ermel jabbed him with an elbow and then took inventory of herself. Holding a pocket mirror to her face, she turned to the left, almost hitting Jeb with the ocean liner, turned to the right, smiled, squinted, and rubbed a blotch of lipstick off her tooth. She tucked the mirror back into her black handbag and turned her attention to the ermine stole, gently, evenly running her hands over the top until all the hairs pointed obediently in the right direction. She looked at her gown, at her boots, at the babies. She told Jeb to wipe their faces with his hanky. She was ready.

The multiple peaks of Toomington Hall’s roof rose and fell above the trees that lined the driveway. Every few seconds, when the landscaping allowed, bigger sections of the mansion broke into view. Fleeting glimpses of a sunburst carved into a gable, of fancy wood siding shaped like fish scales, of a porch big enough to get lost in, brought Ermel to the edge of her seat. She cleared her throat and took a deep breath. Then the motorcar entered a clearing, and she realized she hadn’t been admiring Toomington Hall at all. Those grand peaks had belonged to Sunny Slope Manor, which now towered before her very eyes. She lowered her gaze—and her expectations—and found Toomington Hall in the shadow of its neighbor. Funny how a twenty room mansion could look so small. No matter. She didn’t come to worship Sunny Slope. Everyone did that. She’d come as the specially invited guest of a duchess. Besides, if everything went well, the Newfields might just invite her to Sunny Slope as well.

She grabbed Jeb’s arm and looked into his eyes for reassurance. He looked out the window. She looked out the window too and saw two motorcars parked up by the house, a big one and a small one, both plain and humble, not the motorcars of a duchess. A group of men stood around the motorcars. Ermel stared intently and got a good look at everything when the Rolls turned into the circular drive in front of the house. The big motorcar especially caught her attention. Topless, it had long bench seats facing each other in the back and the words “Police Squad” painted on the side rail that enclosed the seats. All but one of the men, of which there were six or eight, wore police uniforms and shiny badges. When they came to a stop, the policemen spread out and surrounded the Rolls. Ermel looked at Jeb and said, “You dirty dog.”

“Ermel, it ain’t like that. I can explain.”

“Shut up.”

They’d arrived but nobody moved. The chauffeur sat like a stone in the front seat, and the policemen outside stood motionless, alternating their stares between Ermel’s face and their shoes. Some commotion up on the front porch caught everyone’s attention. Mortimer Pugh and three women had just come out of the house and were now scrambling down the steps. Ermel looked at Pugh’s disagreeable face. He didn’t bother trying to crank that big frown of his into something more pleasant. No need. He had her right where he wanted.

He flung open Ermel’s door and said, “This is Mrs. Vigfusson, the nanny, and her assistants. They will be taking the babies now.”

Ermel looked away from Pugh, held her head high, and said, “I think not Mr. Pugh. That ain’t what we agreed to.”

“And what agreement is that Mrs. Railer? Is it in writing? Can you show it to me?”

She didn’t answer.

“This is Sheriff Fowler, Mrs. Railer,” said Pugh, pointing to the man without the uniform. “If you don’t honor our agreement, the sheriff and his deputies will make you honor it. And then I’ll sue you for breach of contract. You’ll lose the re-imbursement money, and, though your husband’s new job is in no way related to the adoption agreement, I wouldn’t be surprised if that disappeared too. You have a lot to gain Mrs. Railer…if you cooperate.”

“Ermel, please. These people ain’t for us anyway,” said Jeb.

“Shut up Jeb! You’re a liar! And so are you Mr. Pugh. And not no accidental one neither, but a rotten one that lies on purpose.” She turned away and stuck her nose back into the air.

“Obstinate little tramp!” huffed Mrs. Vigfusson, who then marched around the motor car and opened Jeb’s door.

“No! No!” said Ermel. “I’ll give them to you! Just give me a minute.” She looked at the three bassinets by her feet. “Hand me that one, Jeb,” she said, pointing to the one farthest away. Jeb picked up the bassinet and started to give it to Mrs. Vigfusson.

“Not to her you idiot!” said Ermel.

Jeb passed it to Ermel, who passed it to Pugh, who passed it to one of the assistants, who walked briskly away and into the house.

“That’s a good girl, Mrs. Railer, a very wise decision,” said Pugh.

“That one next,” said Ermel quietly, pointing to a bassinet.

“Very good Mrs. Railer, very good,” said Pugh, as he handed the bassinet to the other assistant. He then turned and held out his hands for the last baby.

“That’s all Mr. Pugh. That’s all the duchess is getting.”

“Come Mrs. Railer. You know that isn’t our agreement.”

“And what agreement is that, Mr. Pugh? Is it in writing? Can you show it to me?”

Pugh dropped his head and sighed. “Do you know what irrevocable relinquishment means Mrs. Railer? It means that once you say ‘yes,’ and sign the papers, you can’t change your mind and say ‘no.’”

“That’s fine Mr. Pugh, just so long as you can show me in writin’ where I said ‘yes’ in the first place.”

“Sheriff Fowler, I’m afraid your assistance is needed over here,” said Pugh.

The sheriff, an older man with a sagging stomach and two chins, stepped up to the car door. He looked down at Ermel, and she looked up at him. He cleared his throat a few times and said, “Mrs. Railer, you don’t want to go and make a scene. Just think about it for a second. If you make a scene, and there’s a scuffle, the baby might get hurt. You don’t want that now do you?”

“No sheriff, I don’t, and I’m ready to give over the baby just as soon as Mr. Pugh proves that I agreed to it. That ain’t so difficult. It’s all put down on paper, ain’t it?”

“Yes it is, and I’ve seen the papers. Everything is in order.”

“I want to see them too.”

“Mrs. Railer, I’m only going to warn you—”

“No, no, sheriff. If she wants to see it, I’ll show it to her. It will only take a moment.”

Pugh walked briskly back toward the house, leaving behind the fading sound of gravel crunching beneath his feet. The sheriff backed a step away from the motorcar and looked around at nothing. The policemen went back to shoe watching. After a minute, the crunching gravel returned and Pugh stood with a document in his outstretched hand. Ermel took it from him and flipped through the pages.

“Sheriff Fowler, can you help me please?” said Ermel. “What did I write at the bottom of this page?”

“Your name, just like Mr. Pugh said.”

“That’s right. I put my name, and I give my signature, quite a few times if you care to look. That’s for baby Judith. Now look here. What’s that say?”

“‘Ermel Sue Railer.’”

“That’s right. I give my signature all over the place for baby Abigail. Ain’t that so?”

“Yes, Mrs. Railer.”

“Now tell me sheriff, what’s it say right there?”

The sheriff glanced at the document, started to say something, then bent forward and looked again. He stood up straight and looked at Mr. Pugh.

“I know you can read it sheriff ‘cause I wrote as clear as can be. What’s it say?”

The sheriff didn’t say a word.

“‘I say no.’ That’s what it says,” said Ermel. “And here, where it says to give my signature, I said ‘no’ again. If you count ‘em all up I said ‘no’ six times and never once said ‘yes.’”

Jeb groaned. The young cops standing around the motorcar looked at each other. Mrs. Vigfusson hissed something under her breath and ran into the house.

“Give me that,” said Pugh, as he leaned in and grabbed the document from Ermel. “I saw you sign it with my own eyes.” He flipped quickly from page to page.

“No, Mr. Pugh. You saw me sign the other ones, but when I come back from the powder room, you and that tight-ass clerk stopped payin’ attention. I coulda done a finger painting if I’d had the hankerin’.”

“This is deceit! We had a verbal agreement, and that proves your deceit! Your own husband is a witness to that agreement. Jeb, are you just going to sit there and lose everything you worked for. Stand up and take charge! Get control of your wife before it’s too late!”

“Him?” said Ermel with a laugh. “It was too late the day he was born. Now you run along and tell the duchess she ain’t gettin’ Dorthea, the one with the pale blue eyes. She’ll especially want to know that.”

From inside the house came the unmistakable sounds of distress. Mr. Pugh’s head jerked up as he tried to make out the words. After some garbled emotional whispering and hissing, everyone heard, “…didn’t sign the papers? How can that even be possible? That’s his job. You go and tell him to get me that baby, like he promised. And tell the sheriff to do his job!” A few moments later, Mrs. Vigfusson came scampering down the porch steps.

Pugh turned back to Ermel and said, “Let’s just stop for a moment. We can work this out. I just know we can. We’ve come so far, there was bound to be a little hitch along the way. Isn’t that so?” He laughed nervously. “Let me have a word with the duchess. She really is quite fond of you, and I know she’ll want to make you happy. Can we do that? Can we just take a breath for moment? Sure we can. Of course we can. I’ll be right back.” He turned and dashed into the house.

“Sheriff,” said Mrs. Vigfusson, “Her Grace wants you—”

“I heard.”

The sheriff leaned over and poked his head into the motorcar. He cleared his throat a few times before saying, “I hope you know what you’re doin’ girl, cause it ain’t real smart messin’ with these people. They get their way. That’s the way it works. They get their way.”

“But they can’t take her from me if I said no. Can they?”

The sheriff looked up at the stern-faced nanny, back down at Ermel, cleared his throat repeatedly, and said, “No, not today anyway, but like I said, I sure hope you know what you’re doin’.”

Jeb held his head in his hands and moaned. Mrs. Vigfusson ran back into the house, hissing all the way. Pugh dashed out of the house, the opposite direction, and passed her on the way.

“Ok, ok,” said Pugh with a red, wet face. “It’s my fault. My fault completely. I misunderstood Her Grace’s instructions. But it’s all fixed now. Mrs. Railer, the duchess of Sarlione wishes to extend to you her most cordial invitation to a tea party.”

Ermel watched him strain to make his solemn jowls look jovial.

“It’s all prepared, as we speak, in honor of you, Mrs. Ermel Sue Railer. Just like you wanted.”

“We’re leaving now, Mr. Pugh. I’m not interested in that woman’s tea party, and you can tell her so. Driver, take us home.”

“No! Driver! Stay where you are! You’re not going anywhere Mrs. Railer until you hand over that baby!”

“Sheriff, will you be so kind as to inform Mr. Pugh that he can’t have my baby and he can’t make us stay here neither.”

Pugh looked at the sheriff with pleading eyes.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Pugh. The court order says you need a proper agreement. You saw it yourself. That ain’t proper. As it stands today, I can’t make her give up the baby. You work things out in court, and I’ll take care of it, but not the way things stand today. Driver, take these people home.”

“I’m warning you,” said Pugh, “if you leave without handing over that baby, I’ll take everything from you! I’ll take everything!”

Ermel smiled, looked him in the eye, and said, “But you won’t get the thing you want most, now will you? Dorthea belongs to me.” Then she closed her door and told Jeb to close his. As the motorcar rolled down the hill, she lowered her window and said, “Remember, Mr. Pugh, nobody shows up Ermel Railer. Not a two-bit lawyer and not even a duchess.”

Chapter 2

Within days of the baby exchange, every adult in town, up the hill and down, had heard the story. It made its way around the grapevine a few times before coalescing into a tale about the ignorant white trash wife of Jeb Railer who’d insulted a duchess and selfishly condemned her own child to a lifetime of misery. Babies Judith and Abigail had been spared; good fortune had prevailed, and they’d won a reprieve. Dorthea, on the other hand, had won the Railer surname and all the shame that came with it.

It didn’t end with that, though, because in that one day, without a word or an action of her own, Dorthea not only became a Railer irrevocably, but became the most pathetic and pitiable Railer of them all. She had literally made it to the threshold of a miraculous redemption only to have it snatched away at the last second in a freakish turn of events. For the rest of her life she’d lug not only a sorry name, but a pathetic story as well. That story would make her known to most everyone in Prospect Park: “There goes the rejected triplet. It hurts to even look at her”; “That’s her! I can tell by the eyes. And to think, she could’ve had everything”; “My goodness! The spitting image of her sisters, except, of course, they don’t live like animals.”

There is no denying that babies are born into bad circumstances every day of the year, but, seeing Dorthea’s life from beginning to end, a person still has to wonder how these things worked. How come one daughter of a mean alcoholic grows up to be temperate and well-adjusted while another turns out dissipated and troubled? Why does one grown son of a prostitute feed the poor and help the needy while his brother stalks the shadows, indulging dark impulses? Dorthea could’ve played a part in one of these enigmas had she turned out differently. She could’ve been good water from a bad well and left everyone scratching their heads. It could’ve happened, but nobody expected it. They expected Dorthea to turn out like all the others in her family. But what about a third possibility? What about the possibility that she’d turn out much worse?

Better or worse didn’t matter in the early years, though. If anyone had cared to look, they