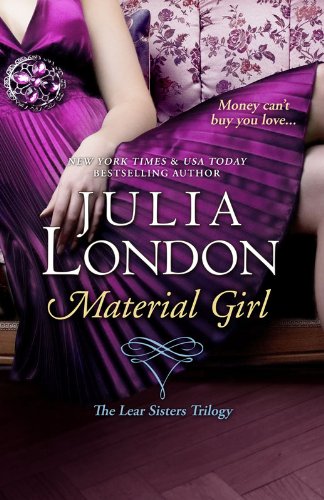

It was humiliating enough to have been brought in at all, much less wearing handcuffs. But then they took all of her belongings, including her belt, made her spread her legs so a female guard could pat her down, and when she was completely traumatized, they took her picture, fingerprinted her, and told her to quit whining; she was not going to see the sheriff, she was going to see a judge. Okay, she had said then, fully contrite for her folly, I give, let me out.

They said they would-if and when a judge said so.

And then they showed her the holding cell into which they had managed to defy physics and force at least a dozen women. Robin’s bathroom was bigger than that cell. It was a nightmare, a bona fide, unmistakable nightmare, complete with bodies under the benches and scary monster-type-looking humans, and she had no one to blame but herself. And damn it, Robin could not stop shivering-they had turned the air-conditioning on to a full-metal-jacket high, undoubtedly to keep the stench down. How long she sat there, she had no idea, and wouldn’t have been the least surprised if days had passed, maybe even weeks, until the door was at last pushed open and a guard came waddling in. “All right, ladies-time to go. You know the drill, everyone on their feet!”

Well, no, she didn’t know the drill, but Robin surged to her feet nonetheless, crowding with the others to get out of that stuffy little room.

They were lead to an open area with chairs and a bank of phones along one wall and told to make their calls. Robin went to a phone, picked up the receiver, grimaced at the greasy feel of it and debated who to call. Oh, hi, this is Robin, and I’m in jail. . . . Her attorney? Seemed logical, but no-she was also Evan’s attorney. Mia? Right. She didn’t answer the phone before noon.

Lucy? Well, sure, if she wanted it spread all over Houston. Kelly, Mariah, Linda, Susan-God, no! Her CPA? He’d probably have a heart attack.

That left only one viable option.

Grimacing, Robin dialed her grandparent’s number, praying to high heaven they hadn’t gone off on some trailer trip. Grandma answered the phone on the first ring. “Hel-lo-oh!” she sang.

“Grandma, it’s me,” she said low.

“Oh, hi, honey!” Grandma said cheerfully. “What are you up to?”

“Grandma, now don’t freak out, okay? I need you to come pick me up. Or get a lawyer-not my lawyer, but . . . oh hell, I’m not really sure what I need you to do-”

“A lawyer!” Grandma gasped. “Why on earth would you need a lawyer? And what is all that racket?”

“It’s a really long and stupid story Grandma, but . . . okay, listen, I’m sort of in a bind. You shouldn’t panic or anything, because like I said, it’s reallyreally stupid-”

“Where are you, Robbie?” Grandma asked, her voice going shrill.

There was no good way to say it. Robin forced a laugh. “You won’t believe this, Grandma!

Ha haaaa, I’m . . . I’m . . . in jail.

They probably heard her grandmother’s shriek throughout the entire retirement community. “Jail!” she cried out. “Jail? Oh no, not jail! Elmer! Robbie is in jaaaail!”

Robin heard the receiver on her grandmother’s end bounce on the phone table. “Grandma!” she cried into the phone.

“Robbie, is that you?”

Thank God, Grandpa! “Yes, yes, it’s me, Grandpa! Is Grandma all right?”

“Are you really in jail?”

“Yes, I-”

“Oh yeah? What’d you do?”

“I didn’t really do-”

“Drugs?”

“Grandpa! Of course it wasn’t drugs!”

“Well then, what? Murder?” He chuckled appreciatively at his own jest. Robin stared at the phone cradle in front of her. Why hadn’t she realized before this crucial moment that her grandparents were insane? “Oh dear, it wasn’t murder, was it?” he asked, his voice suddenly anxious.

“Of course not!” she cried. “It’s too long to explain now, but Grandpa, please come get me. This place is horrible! Everyone smells, and who knows why they are here, and the guards are just . . . just mean, and I have no idea how long they will hold me or anything, but please, please come get me,” she said, feeling suddenly and dangerously close to tears.

“Well, of course we’ll come get you, Robbie-girl! You just hold tight. We’re gonna come get you.”

“Thanks, Grandpa,” she whispered tearfully, and heard him shout at Grandma to hurry up as the phone clicked off.

Feeling a little better having called in the cavalry, Robin endured another interminable wait until they were led, single file, into another long room where a judge’s bench was elevated above the rows of wooden benches. They formed two groups, men and women on opposite sides of the room. Now Robin was feeling particularly slimy. The last seventy-two hours had been a personal trip through hell, and all she wanted was out-she had never felt so alone or so vulnerable or so insane in her life. What sort of moron picked a fight with a cop?

She shivered. They waited. She wondered what time it was, had that slow and thick feeling of having flown through too many time zones on a long transatlantic flight. When at last the judge did arrive, Robin was surprised; the diminutive African American probably didn’t reach five feet.

The bailiff announced Judge Vaneta Jobe and told them all to rise. Judge Jobe climbed up onto her big black high-back leather chair, and with her head barely visible, and her feet probably swinging a foot above ground, let her gaze travel the crowd. “All right then,” she said, slipping on a pair of round, silver-framed glasses. “Listen up, everyone. Y’all have some rights you’ll need to know about. . .” She proceeded to inform them, in a booming voice that belied her size, of their rights and the different types of bonds available to them. Then she announced she would bring them forward to hear the charges being made against them, and when she had finished her speech, she asked, “Is that just clear as mud? Let’s begin, Mr. Peeples.”

The bailiff picked up a sheet and squinted at it. “Rodney Trace.”

A man from the third row of benches stood and came forward, his head hung low. When he approached the bench, Judge Jobe glared down at him. “Seems like you gone and done a stupid thing, Mr. Trace. How many times are you gonna be stupid? Until you kill someone? Or until they send you down to the farm?”

Rodney Trace shrugged.

Judge Jobe sighed. “Bail set at twenty-five thousand dollars. Who’s next on our hit parade, Mr. Peeples?”

Horrified, Robin watched as Judge Jobe and a long string of people who alternately tried to argue their charge or took whatever bond she set with a shrug. She was beginning to feel less and less optimistic about what would happen to her, and started like a jumping bean when the bailiff finally called her name. She hurried forward, clasped her hands tightly in front of her and tried very hard not to shiver.

The judge leaned over the bench to have a better look at her, shaking her head. “Urn, um, um . . . don’t know what’s got into you, girlfriend,” she said, and picked up a manila folder. “Do you think this town belongs to you?”

Was she supposed to answer that? Robin glanced uneasily at the bailiff. “Uh . . . no,” she stammered. “No, of course not.”

“Then why were you so nasty to Officer Denton?”

“I, uh . . . I d-didn’t know that I was.”

The judge peered over the tops of her round glasses at Robin. “You trying to tell me that you didn’t know you were mouthing off to him? Or that you were being nasty? Or that by refusing to give him your name, or provide your license, or proof of insurance, that you were being disrespectful? Is that the way you do people, Ms. Lear?”

“No. . .”

“No?”

“Uh, yes . . . well, no,” Robin stuttered.

The judge snorted, looked at the bailiff. “Ms. Lear got herself an attitude problem, Mr. Peeples. That superior attitude got her into a little bit of trouble, didn’t it?”

“It sure did, Your Honor.”

“I’m surprised Ms. Lear managed to make it this long before someone knocked her down a notch or two.” The judge tossed the file down and bestowed a fierce frown on Robin that sent another shiver down her spine. “You need to wake up and smell the coffee! How many of your fine and fancy friends get themselves thrown in jail for talking trash?”

“I don’t know any,” Robin answered truthfully.

“Maybe that’s cause they don’t go around thinking they’re better than everyone else. If you’re gonna walk around thinking you are, you’re gonna keep making trouble for yourself, do you understand me?”

“I don’t think I’m better-”

“I said, do you understand me?” Judge Jobe demanded.

“Yes, ma’am,” Robin answered softly.

“I’m gonna accept your plea of guilty for driving without a license or insurance and fine you seven hundred fifty dollars for wasting my time.”

Robin blinked. When, exactly, had she pled guilty?

“Now follow the deputy here, and try not to be annoying,” the judge said and handed the deputy a piece of paper. He pointed toward the door; Robin walked, head down.

And found herself waiting in another large room after she had received her personal property, which consisted of a belt, a Cartier watch, an emerald ring, and a half-empty purse, in which, fortunately, there had been a lone credit card in the side pocket. The very helpful deputies also gave her a paper with the location of her car and pointed to the window where she would pay her fine along with everyone else in Houston.

Robin made the mistake of asking the clerk when she could pay, which earned her a reprimand to be seated while the clerk and her friend chatted away as if they had nothing else to do. Dejected, exhausted, and feeling terribly low, Robin sat, wondering if it were possible to get a bazooka in here to break up their little coffee klatch. Her head ached, her back ached, even her butt ached from sitting for so many hours on rock-hard benches like the one on which she was sitting now. She felt grimy, her mouth tasted rank, and her stomach was in knots. All she wanted to do was go home and burrow under the covers of her bed for the next five months.

She waited.

Until someone sat hard next to her, jostling her almost off the bench, that she realized she must have been drifting on the edge of sleep. With a jump, Robin blinked, looked to her left. A man with impossibly broad shoulders had fallen onto the bench next to her. He was wearing a weathered leather jacket and faded jeans, had a crop of thick dark brown hair, and when he turned to look at Robin, he smiled and said with a wink, “Hey.”

“Get real,” she muttered, and scooched over.

“Oh come on, it can’t be that bad,” he remarked, as if they were sitting in a park somewhere.

“What would you know?”

“Okay, so I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to bump into you. Truce?”

She really was not in the mood to make friends just now. With her hand, she gestured for him to move. “Just . . . please go away.”

“Believe me, lady, I’d love to oblige you,” he said, his voice less friendly, “but in case you haven’t noticed, it’s pretty crowded in here.”

“You can find another seat.”

“Maybe you’d like to find another seat. I’ve been waiting two hours.”

Only two hours? How did he get out so fast? That infuriated Robin-she had to wait all night, and this dude was out in two hours? “I was here first,” she pointed out.

“Ah,” he said, nodding. “Clearly, I misunderstood.” But instead of moving, he just settled in.

Robin glared at him. “What do you think you are doing?”

“Like I said, the room is full, so unless you can produce a deed or something that proves you own this bench, I’m not going anywhere.”

“Great,” Robin snapped, and abruptly stood up.

“Nice talking to you, Miss Congeniality,” he said as she started to push her way down the row.

Three or four seats down, she glared at two Hispanic men who, after exchanging a wary glance with one another, moved to make a seat for her.

She squished in between them like a sardine, then glanced down the row just as the jailbird got up and sauntered off. Bastard! But Lord . . . what a saunter that bastard had! Even in her dejected, repulsed, and generally miserable state, Robin could not help noticing how fine he was in his ancient denim jeans and briefly wondered what he might have done to land himself in hell.

He suddenly turned and caught her staring at his backside and flashed her a lopsided, knew-it smile. Robin frowned deeply, turned her attention forward, and did not look again. Except once. Maybe twice. By the time they finally called her name, she had definitely lost sight of him and was in such a hurry to get out of that stinking hellhole that she almost collided with him when she turned from the window, clutching her freedom on a receipt marked PAID.

“Oh man. Well, hello again, Sunshine,” he drawled.

“Jesus!” she exclaimed, holding the hand with the receipt over her flailing heart as she glared up at him. “Can’t you take a hint?”

“Hey, Queenie, I’m just waiting in line like everyone else.”

“Uh-huh, right,” Robin responded irritably and wondered for a split second why men thought women were so ignorant of their motives.

The man all but choked. He stared down at her, his copper-brown eyes wide with surprise. And then he laughed. Laughed. Laughed so roundly, as if that was so hilariously preposterous, that several heads turned in their direction. But he didn’t seem to care-he leaned forward, bent his head until his mouth was just an inch or two from her cheek, and said, “Sunshine, you’re cute” -he paused, lingered there for a tiny moment, his breath warm on her face, so close that she could smell his cheap (but not altogether unpleasant) cologne- “but no way are you that cute. And you’re mean.” He straightened up and calmly stepped around her to the payment window.

Okay. Well. She was now officially in hell. Some . . . jail guy . . . had just dissed her, and it was so unbearably humiliating that Robin beat a hasty retreat out the double glass doors, into the lobby of the processing center, clutching her purse and her receipts like a mad escapee, frantically searching the milling crowd for her grandparents.

Fortunately, her mother’s parents were easy to spot. There was her grandfather, who had the distinct misfortune to have been named Elmer, and the even greater misfortune, in his declining years, of actually resembling Elmer. He was round and squat with hugely enormous feet typically encased in white Easy Spirits, which heralded his arrival a good city block before him. And in fact, it was Mr. Fudd’s shoes Robin saw in the lobby before she saw him.

Her grandmother, Lil, was the physical opposite of Elmer. She was tall and reed thin, and wore big pink-rimmed octagonal glasses that covered her cheeks and eyebrows and made her eyes look like big blue stop signs. She also wore Easy Spirits. The taupe ones.

Grandma spotted Robin and came hurrying like a squirrel across the lobby, darting in and around people in her haste to get to her granddaughter. “Robbie!” she exclaimed, and grabbed her in a bear hold, nearly squeezing the breath from her. “Oh my God, sweet pea! What has happened!”

“Robbie-girl, you all right?” Grandpa asked, rescuing her from Grandma’s grip.

“I’m fine,” Robin insisted. “It’s really so stupid. I’ll tell you all about it in the car, but please, let’s just get out of here,” she urged, ushering them in the direction of the door.

Grandpa had scored a prime parking spot into which he had maneuvered his Ford Excursion, an SUV the size of a small condo. Robin gratefully crawled into the cavernous backseat.

“Buckle in, hon. Now, are we going to hear what you did?” Grandma insisted, fastening her seat belt.

Best to get it over. “I got stopped for speeding-”

“Speeding! Where?” Grandpa insisted.

“On six-ten-”

“Well now, six-ten, that’s just a death trap.”

“-And I guess I sort of mouthed off a little. I mean, I wasn’t doing any faster than anyone else, and I told the cop so.”

“That’s my girl!” Grandpa said proudly as he coasted out of the parking lot.

“So he asked me for my license and registration, but the thing is, I had left them on my desk at work-by the way, Grandpa, I need to go by my office and get my wallet, okay? Anyway, I didn’t have my license or registration, and suddenly I’m a criminal! So the cop told me to step out of the car, and . . . well, I just thought . . . I just thought that he was overreacting and I shouldn’t have to step out of the car.”

“Well, he should have taken your word for it!” Grandma said with an indignant nod of her head. “Surely when you told him your name he ran some sort of check or whatever they do in their cars to make sure you weren’t lying!”

Robin squirmed.

Grandma swiveled sharply to look at her. “Well?” demanded Grandma. “Didn’t he?”

Robin sighed, leaned her head against a headrest covered with a pink baby T-shirt. “I was really tired and really cranky, and I didn’t exactly tell him who I was. I just sort of thought it wasn’t his business. So he arrested me.”

Grandpa gave a shout of laughter, but Grandma threw a hand over her mouth and stared at Robin in horror for a moment. “Can they do that?”

“Apparently,” she answered dryly. “He arrested me for failure to identify myself, driving without a license, and driving without insurance.

“Oh my goodness, what does this mean?” Grandma asked.

Robin grimaced at her grandmother’s look of shock, and turned away, to the window, where cars were swerving from behind Grandpa and whizzing past as he pushed the SUV up to sixty. “It means they slapped me with a Class C misdemeanor, took seven hundred fifty dollars for their trouble, and told me to go home.”

“Did you see any murderers in there?” Grandpa asked.

“Elmer! This is no joking matter!”

“I didn’t think that was joking!”

“Grandpa, don’t forget to go by my office, okay?”

Grandpa acknowledged her request by putting his blinker on a good two or three miles before their exit.

“Well, you can’t work today,” Grandma said in a huff. “You don’t want everyone knowing why you were late-Aaron wouldn’t like that at all.”

Honestly, Robin didn’t know anymore. Maybe Dad would think she deserved to be publicly humiliated. “I just need to get my things and a couple of files, that’s all. Maybe Grandpa can go in for me,” Robin said absently.

“I just can’t believe you have been arrested,” Grandma said and shook her head again.

Too exhausted to think, Robin stared out the window, felt her eyelids growing heavy. The next thing she heard was Grandpa, saying, “Uh-oh. Looks like a fire.”

Robin opened her eyes and glanced out the front windshield. As her mind began to grasp that they were on the street of her office, she suddenly grabbed the back of Grandpa’s seat. “Oh my God!” she cried. It couldn’t be. Couldn’t be! Robin quickly counted the floors of her office building and felt her heart sink to her toes. Oh yes, it could be, and it was. The LTI offices were on fire. Her office was on fire.

In front of her, Grandpa shook his head. “Some fool probably left a cigarette burning or a computer on or something like that,” he opined, disgusted.

Left something on . . . the suggestion was suddenly clawing at Robin’s throat, choking her. The coffeepot.

She had left the coffeepot on.