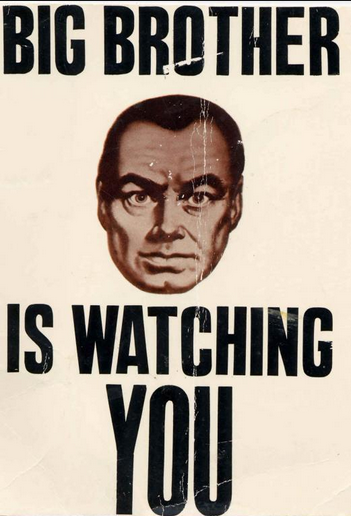

Dorian Lynskey from LitFub on how the message of a book can change Radically Over Time: “Everybody wanted Orwell’s ghost on their side.”

On November 2, 1950, Hugh Gaitskell, Chancellor of the Exchequer for Britain’s Labour government, accused his opponents in the Conservative Party of “what the late George Orwell in his book, which honourable members may or may not have read, entitled ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ called ‘doublespeak.’” Orwell’s final novel had been out for 17 months and Gaitskell was confident that at least some of his fellow MPs had already read it. Many had, including former prime minister Winston Churchill, who told a colleague that it was “a very remarkable book.” Propelled by the unexpected success of Orwell’s anti-Stalinist fable Animal Farm, published four years earlier, 1984 landed in the world with a bang and it has been exploding ever since.

The most notable thing about Gaitskell’s statement, however, is that doublespeak doesn’t appear in the novel: he was misremembering the concept of doublethink. Nonetheless, it entered the political lexicon during the 1950s, alongside Big Brother, Newspeak, the Thought Police, Orwellian, and so on, and those words have never gone away. In fact, the novel is more famous for its language than its characters or plot. By pinning down the political phenomena of the 1930s and 40s with dramatic, futuristic terminology, the ailing author secured cultural immortality.

Journalists are magpies for novelty, especially shiny semantic baubles that they can use to brighten up political prose. References to popular works of fiction tend to tarnish into clichés, like Game of Thrones analogies now, but Orwell’s neologisms have retained their luster for 70 years because they have entered that small, exclusive zone that lies beyond cliché: the place where words become so embedded in the language that they are no longer read as references. Such words as thoughtcrime, unperson, and memory hole require no explanation. Twenty years ago, the creators of the television show Big Brother attempted to deny any relationship to Orwell’s character, as if the concept of an invisible, all-seeing authority figure with that name were as authorless as a folk song. (Lawyers for Orwell’s copyright-holders lucratively disagreed.)

Search Twitter for phrases from 1984, and you’ll find that they are rarely qualified by a mention of “the late George Orwell.” You will also find that some of them appear in contexts that bear little resemblance to the author’s original definitions. Orwell’s Thought Police, for example, were based on the Stalinist practice of persecuting citizens for things they hadn’t yet said or done. It’s unlikely that he would have enjoyed seeing the term applied to a twitter-storm following a contentious remark.

More an essayist than a novelist, much though he wished otherwise, Orwell thought the message of 1984 was obvious: it was a satirical attack on the totalitarianism of Stalin and Hitler, and on the potential for totalitarian thought to take root in democracies. Just weeks after publication, however, he felt compelled to issue two clarifying statements to the press after reading reviews which interpreted the book as a condemnation of all forms of socialism, including the Labour Party, of which he was supporter.

Orwell’s publisher Fredric Warburg concluded that the statements “didn’t do two pennorth of good.” Readers continued to see what they wanted to see.