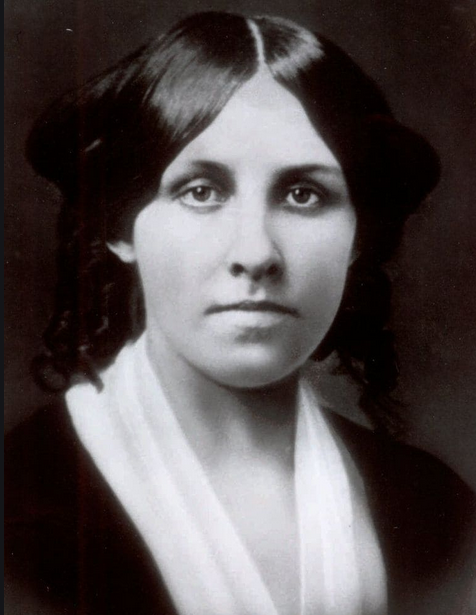

Louisa May Alcott’s forgotten thrillers are revolutionary examples of early feminism. Stephanie Sylverne from CrimeReads has the story… Support our news coverage by subscribing to our Kindle Nation Daily Digest. Joining is free right now!

Louisa May Alcott is having a moment. Another film adaptation of Little Women hits theaters this winter (a BBC production aired on PBS Masterpiece only a year ago), two separate Little Women-themed cookbooks were released in October, and a new essay collection, March Sisters, featuring work from Kate Bolik, Jenny Zhang, Carmen Maria Machado, and Jane Smiley, published just this past summer, attests to the novel’s enduring legacy.

Generations of scholars have examined Alcott’s personal life (Civil War nurse, “spinster,” possibly a lesbian), discussed ad nauseum her family’s radical political activism (her father was not only a transcendentalist and an abolitionist, but believed in absolute equality of all races); and marveled at her childhood milieu, surrounded by people like Emerson and Thoreau and her mother’s friends, Lucretia Mott and the Grimke sisters, as well as meeting Frederick Douglass and his wife. But far less attention is paid to her sensationalist “blood and thunder tales”—pulpy thrillers she wrote early in her career, often using the pseudonym A.M. Barnard.

This was the work Alcott was passionate about before the financial needs of her family forced her into writing what she called “moral pap for the young.”

“I think my natural ambition is for the lurid style,” she said in an interview. “I indulge in gorgeous fancies and wish that I dared inscribe them upon my pages and set them before the public. How should I dare interfere with the proper grayness of Old Concord? The dear old town has never known a startling hue since the redcoats were there. Far be it from me to inject an inharmonious color into the natural tint. And what would my own father think of me … No, my dear, I shall always be a wretched victim to the respectable traditions of Concord.”

Once Little Women catapulted her to fame in 1868, there was no going back to those “gorgeous fancies,” even anonymously. She wrote “moral pap” for the money, and the rest was left behind. Even if she wanted to continue, her time was taken up with her publisher’s requests and the demands of chronic illness (some believe she suffered the after-effects of mercury treatment; some believe she had lupus).

Read full post on CrimeReads