Whether it’s John Milton or Danielle Steel, who decides which books are great? Livia Gershon from Jstor analyzes what makes a “great book”… Support our news coverage by subscribing to our Kindle Nation Daily Digest. Joining is free right now!

Do you feel guilty picking up a romance novel or a comic book when you still haven’t finished Paradise Lost? You might trace your anxiety to the development of the concept of “Great Books” which, the historian Tim Lacy explains, occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. At that time, Lacy writes, U.S. universities were turning into something different from the longstanding European model of higher education. Rather than focusing on “mental discipline” and classic Greek and Latin texts, students often specialized in particular disciplines designed to prepare them for professional careers. Modern science was becoming more central to universities, and students had more chances to pick elective courses.

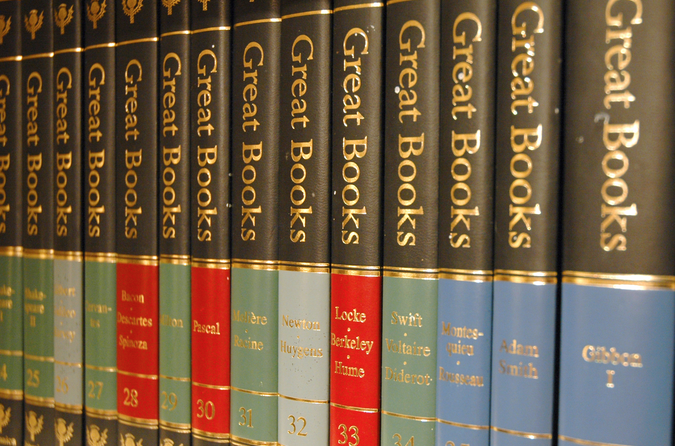

In the face of these pressures, some men and women of letters demanded a different kind of education. They sought out what the British critic Matthew Arnold called the chance to engage “the best which has been thought and said in the world.” Lacy writes that this wasn’t just an elite phenomenon. In the U.S. and in Britain, a growing publishing industry and new public libraries put more books than ever within reach of the reading public. To figure out what to read, people browsed newspaper reviews and lists of the “hundred best books.” Publishers met the demand with series like the Harvard Classics’ “Five-Foot Shelf of Books.”

Lacy writes that intellectual elites who compiled these lists and collections sometimes had a commercial motive but, for the most part, really hoped to foster a “democratic culture.” That was partly a utopian dream—that a nation of readers would be classless and fully self-governing—and partly a reaction to sociopolitical problems. Some intellectuals worried that a society previously unified by a religious worldview was fracturing. To Arnold, religion was shrinking from an engagement with the world involving “all the human faculties” into a mere matter of moral judgments, leaving a space for “culture” to fill.

Read full post on Jstor