EVERYTHING IS PERFECT WHEN YOU’RE A LIAR

EVERYTHING IS PERFECT WHEN YOU’RE A LIAR

Today’s Bargain Price: $2.99

EVERYTHING IS PERFECT WHEN YOU’RE A LIAR

EVERYTHING IS PERFECT WHEN YOU’RE A LIARToday’s Bargain Price: $2.99

Really, it’s okay to spread the word when you find a BEST PRICE EVER on a Barbara Freethy novel!

Don’t Say A Word By Barbara Freethy

Don’t Say A Word

Don’t Say A WordToday’s Bargain Price: $0.99

On Friday we announced that John Hampel’s Glass House 51 is our Thriller of the Week and the sponsor of thousands of great bargains in the thriller, mystery, and suspense categories: over 200 free titles, over 600 quality 99-centers, and thousands more that you can read for free through the Kindle Lending Library if you have Amazon Prime!

Glass House 51 is the insanely amazing adventure—or misadventure—of a lifetime, of one Richard Clayborne, a hard-charging young marketing maverick at gigantic AlphaBanc’s San Francisco branch.

Hyper-ambitious Richard has been offered an intriguing assignment: Get online via NEXSX and make e-time with the lovely, brilliant (and doomed) Chicagoan Christin Darrow. All to set a trap for the reclusive—and very deadly—computer genius, Norman Dunne, aka the Gnome.

Why? Three lovely young women dead in the streets of Chicago. And the Gnome, a former AlphaBanc employee, is the main suspect. But there just might be another AlphaBanc agenda in the works. . . .

Little does clueless Richard know what is in store for him and the innocent Christin: a tangled, twisted journey through the AlphaBanc underground, but by the time he realizes it, they’re in too deep to get out.

Glass House 51 transports us to the future present where information on an individual can be so comprehensive, so insidiously granular and minute, that people can become information “specimens” kept by perverse “collectors” . . . like butterflies in a virtual bottle.

Glass House 51 is humbly dedicated to George Orwell and Aldous Huxley, massive contributors to the collective conscience of our modern age. They saw it coming; they saw it first; they warned us. We learned nothing.

Prologue

It is the back door to the brave new world. A tremendous gateway. Leonard Huxley’s eyes reflect the glow of his heated computer screen as he prowls the soft silicon bowels of AlphaBanc, the largest financial services company in the world, jumping from file to amazing file. This last one is really fabulous, one of a collection of video clips obtained from God knows where, labeled NSXMD71109, depicting an attractive scantily-clad young woman in red high heels holding a glass of wine and traipsing around what appears to be her living room, obviously enjoying herself.

“F-fantastic stuff,” Huxley softly stutters, licking his lips and banging the top of his ancient battered monitor to try to jump these jangling chartreuse and violet images back into a semblance of real colors. Regretfully, he closes the clip and yawns, glances at the time: two a.m. He’s been at it for four hours straight, but he can’t stop now, he’s finding almost too much to comprehend: electronic acres of bank records, credit reports, medical archives, criminal records, phone call listings, video and audio files, all elegantly sorted by social security number, DMV code, surname, maiden name, credit card numbers . . . dozens of primary keys, relentless unending columns of people’s frantic lives—incredible, amazing, and strangely evil. Geoff was absolutely right.

It is even more than Huxley had imagined. Ever since Geoff had hinted to him what was behind the silicon curtain, Huxley had begged him for a way in, an ID and a password. And finally, in the last encrypted email Geoff Robeson had sent, he had attached them. It was the gift of gifts, but the decoded letter, which Huxley feels compelled to open again this late hour, is unsettling:

Leonard: I fear I’m in trouble. I confronted Bergstrom this morning and he was, as I predicted, extremely upset with me. I finally told him that our current activities at AlphaBanc are clearly beyond the pale and that we must reconsider our plans. He was so violently angry that I walked into the door jamb on my way out, something I have never done before. So, I must confess, aware as I am of the magnitude of the dangerous game they are playing, I now fear for my life. Until later, my anarchistic friend.

— Geoff.

Huxley closes the message again, wonders exactly how much trouble his friend might be in. He has never known him to exaggerate, one of the reasons he loves to correspond with him; the man is a straight shooter. So many others out there are frauds and liars but Geoff Robeson is just who he appears to be, a fifty-four-year-old economist at AlphaBanc in Chicago, a caring, intelligent, blind black man, and most importantly, a great friend. And he, Huxley, is pleased to be actually himself online, a poor twenty-year-old computer science dropout who takes great pleasure in trying to refute Robeson’s thoughtful observations of a world that both of them have really never yet seen.

It is only one week later that Huxley wanders by a newspaper vendor on Lincoln Avenue, idly scans the front page of a Chicago Sun-Times and finds: SIGHTLESS MAN PLUNGES 64 FLOORS. The story that follows describes the windows removed for maintenance at One AlphaBanc Center and the firm’s chief economist (described by AlphaBanc employees as seeming to be depressed lately) who must have wandered past the barriers to take the fateful, weightless step.

J-just like that Tarot card, The Fool. Huxley fights back tears, trying not to believe what he reads. He should have tried to do something; he knew that Geoff might be in great danger. He knew of the ruthlessness with which AlphaBanc pursued its objectives, fuel for many encrypted tirades to his blind mentor which just might have persuaded him to take the dangerous steps he had into Karl Bergstrom’s office and thence to an evil free fall . . . the fool.

He begins sobbing softly on the street corner. His great good friend . . . gone. In the end, nothing more than one of AlphaBanc’s pathetic doomed fools. . . .

Chapter One

Richard Clayborne can’t seem to breathe.

Who could do something like this?

The photograph embedded within the email he has opened is vivid and disturbing, centered mutely, outrageously, on his computer screen.

Oh God . . . there must be some mistake, Clayborne thinks as he forces himself to examine more closely the message and the repugnant image. But it is specifically addressed to him alone at alphabanc.us.west and worse yet, contains what seems to be a warning, just for him.

He can’t believe it. Just when everything was beginning to go so well for him again—actually, spectacularly well.

“Richard, don’t you have a meeting right now?”

“What?” Clayborne jumps, exhales hugely, looks up from his monitor.

Mary Petrovic, one of the members of his marketing team, is standing in his office. “Don’t you have a teleconference now with Chicago?”

“Oh! Omigod!” He checks his watch. “You’re right!”

“Are-are you okay, Richard? You look kind of sick—”

“I’m fine, I’m fine . . .” he mutters, quickly clearing the picture before she can see it. He takes a deep breath, momentarily closes his eyes, wishes he could dismiss the image from his mind as easily as it disappeared from the screen.

“Are you sure? You don’t look very—”

“I’m okay!” he nearly shouts, immediately regretting his anger. It’s not her fault he’s upset. He pushes away from his desk and grabs his suit coat. This is definitely not a good omen. The most important meeting of his career—maybe his entire life—and he almost missed it.

Breathing hard, Clayborne blinks in the daylight that assaults him as he hurries down the windowed corridor on the thirty-fifth floor of AlphaBanc West, the San Francisco branch of AlphaBanc Financial Services, the largest banking, consumer credit, and marketing services firm in the world. It’s still hazy this time of the morning, but considerably brighter than the dim staircase he has run up from two floors below, rather than wait for the elevators.

Now I really don’t feel good about this, he thinks as he lopes down the hallway, the disturbing email adding a quantum jolt to the nagging bad feeling he’s had ever since he was offered this special assignment.

“A tiny bit of subterfuge,” was how it had been described to him by Alan Sturgis, AlphaBanc’s senior vice-president of corporate marketing who had flown in from Chicago to personally pitch him on the project. Which immediately impressed Clayborne with just how big a deal this really is to them.

All to catch a Gnome.

“Er, did you say, Gnome?” he had asked Sturgis, sitting across from him in his small office hugging one of the interior walls in AlphaBanc West’s prestigious marketing department.

The chair squeaked as Sturgis leaned back before answering him. He was a big thickset man with a florid face and a balding head surrounded by a reddish scruff of hair on the sides. He panted slightly as he talked, his voluminous dark blue pinstripe suit quaking as he shifted repeatedly in the small chair, trying to get comfortable. “Well, that’s what he calls himself—on the Web. The Gnome. His real name is Norman Dunne. But he takes great pride in being ‘the Gnome,’ believe me. He’s a computer genius, and we know that for a fact because he used to work for us. Not all that long ago, actually.”

“No kidding? Why did he leave?”

Sturgis sighed. “It’s a long story, not worth getting into now, but it certainly hasn’t hurt his efforts to break into our computer systems. He knows every weakness, every flaw. I’m embarrassed to say that he’s recently—hacked, is the appropriate term I’ve been told, into our corporate databases and stolen quite a bit of valuable client information.”

“What did he take?”

“Sorry,” Sturgis smiled at him, “can’t tell you that. It’s classified. But I think you can understand, Richard, how important it is that news of this crime is never made public. AlphaBanc is recognized as an ultra-secure institution, particularly our McCarthy operation, and if word of this got out it could cause us tremendous damage. It would take years and cost us a fortune in PR to regain our customers’ trust.”

Clayborne nodded. He understood. AlphaBanc’s reputation for security is unparalleled in the financial world.

“So, you can see why it’s so important that we track him down before he gets a chance to peddle this information—and stop him before he can do it again. And you can also see why we’re not immediately involving the police in this matter. At least not until we’ve positively located him, when we can be assured of a swift, hopefully, very low-key arrest.”

“I understand. I assume then that he’s . . . hard to find?”

“Oh, yes, exactly,” Sturgis snorted. “That’s the whole point. He’s gone completely underground. Goes by any number of fake identities when he does happen to surface. Even with modern electronic means and our surveillance, er, what we call sentinel, databases, he’s impossible to locate. He knows all the tricks. You see, Richard,” Sturgis leaned heavily over the desktop and lowered his voice, “that’s exactly why we need your help. Instead of us trying to find him, we’re going to get him to come to us. . . .”

As Clayborne rushes onward to his teleconference he reconsiders the assignment: could he possibly back out? It seems unthinkable now; he’s already accepted and this high-visibility meeting with AlphaBanc’s top executives is partially his reward for signing on. How would it look if he just quit? Besides, it’s the opportunity of a lifetime, one he’s been waiting for since he first came here six years ago. He can’t give it all up just because of one errant email.

“Whoa! Richard, watch out, man!” says someone jumping out of his way, a blur in his peripheral vision.

Clayborne stops short, realizes he has almost run into a coworker carrying a stack of printed reports. “Sorry, Stevie, I guess I wasn’t watching—”

“You looked like you were in another world, man.”

“Yeah, got a lot on my mind, I guess. And a teleconference in the library—right now. Gotta run!” he says, still startled by the glimpse he had caught of himself in the corridor windows as they almost collided. Beyond the basic good looks he had inherited from his dynamic father, the supersalesman Bruce Clayborne—square jaw, keen blue eyes and the unruly skein of chestnut hair on top—he looked frazzled. Certainly not the image he wants to project at this meeting.

He shrugs it off, tries to smooth his hair as he sprints into the empty library, buttons his coat and fidgets with the tie he has chosen to wear for the meeting, the two hundred dollar Stefano Ricci, his best, and runs over to the big monitor on the wall. He powers it on and flops down in the red leather chair facing the small camera perched above the unit. He leans forward, picks up a thin keyboard from a side table and logs onto the system. A series of numbers immediately scroll across the screen. He wipes sweat from his forehead and waits for the response from Chicago, world headquarters of AlphaBanc Financial Services, or AFS, as proclaimed by the ubiquitous golden insignia centered on the startup screen of every computer in the enormous AlphaBanc network.

He slowly shakes his head as he glances around the small sumptuous library, its walnut paneling softly illuminated by green glowing banker’s lamps on each table. Here at last. He still can’t believe his luck. At thirty-one he is a senior marketing manager and one of the project leaders of AlphaBanc’s wildly successful “Biggest Best Friend” campaign. Obviously a very good place to be in the organization for in only a few minutes he’s about to meet the big man himself, the one at the top of the gigantic AlphaBanc pyramid of 350,000 employees, Karl Bergstrom.

Hurry up and wait, he thinks as he sees his name added to a long queue on the screen. He pushes his fingers through his hair, wonders if he’s worrying for nothing. Maybe the message was just a hoax, or some kind of sick joke. His part in the scheme is quite simple, anyway, a little harmless online chit-chat with some woman in Chicago, nothing more. Piece of cake.

Of course, he’s got to assume a fake Web identity and make contact through NEXSX, the dubiously popular Internet adult conferencing service—but in terms of the greater good of the mission, really not a big deal. AlphaBanc, he’s sure, has everything worked out.

Or have they?

He wonders again if he should just tell them to get someone else. Or tell them about the ominous email? His stomach tightens; it’s an excruciating decision. He’s worked so long and hard to get to this moment. Of all the possible candidates available to them, they’ve asked him to help them out. No one else.

Maybe it was all the blood. He’s always been squeamish about blood and that photograph of what seemed to be a police crime scene had been virtually drenched in it. Who was that poor young woman? Who could have sent it? The From address, which had seemed real enough, he was sure now was undoubtedly bogus, untraceable, but the brief message that accompanied it seems to have found its mark, him:

This is what they are hiding, Richard. This is what has happened to the others. It might happen again. Think about it.

Chapter Two

In a small northside Chicago apartment, a grimy, smoke-blackened window separates the outside world from the Gnome’s lair, a darkened room crammed to the ceiling with humming computers and networked electronic gear. The window is always closed and shaded, but this particular fall morning it has been propped open in an attempt to refresh the heated atmosphere of the electrified space behind it.

The outside air is quite cool, however, and it is not long before Norman Dunne, a slight, balding man sitting before an array of computer monitors, pulls his worn sweater closer and squints in the unaccustomed brightness. He gets up from his swivel chair and shuts the window, draws the shade. The room darkens once again, lit only by glowing monitors and a multitude of red, green, and gold indicator lights—just the way he likes it.

He turns his attention back to the screens, stops to scrutinize one containing a series of online accounts he has been monitoring. He moves his mouse, clicks, and enters the private realm of a young woman logged onto the NEXSX site. A few moments later he smiles and enlarges a particular window.

She’s wearing red today, and not very much of that.

Dunne licks his lips and taps on the keyboard to more precisely calibrate the screen color.

A study in scarlet. How very lovely.

He grins. He’s touched. She’s choreographed this sweet and minimalist video ballet just for him. The unbelievably beautiful and absolutely unattainable—in the real world—Katrina Radnovsky, has done it for him. Or, actually, for the glib, gorgeous, blue-eyed muscular hunk she thinks he is.

Dunne sighs. Anyway, I’ve got her now.

An amazing catch, and right here in Chicago. Perfect . . . absolutely perfect, muses Dunne as he idly browses the massive amount of data he has gathered on her: email and phone logs, credit card numbers and pins, summaries of her financial transactions, cross-referenced listings of all known family and friends, business associates, suspected lovers, past and present . . . and recently, the lab test results of her latest physical exam. He knows who she talks to, what she says, where she shops, what she buys . . . who she is. But in the end it was she, herself, as it always was, who let him all the way in.

Dunne smiles as he scrolls through her file, thinks that this is a very good specimen indeed. One of the finest in his collection. The only bothersome thing is that she now wants to meet him, in real life.

Damn . . . not again.

He gazes at her incredible image and smiles bitterly. He’s simply too good at being who he is not. Too suave, too convincing. Just too damned good. It’s a thrilling and satisfying game, but it always comes down to this, a looming real-world encounter that the diminutive computer genius simply cannot pull off.

As always, he frets, mutters to himself, wrings his hands. Time’s run out with her. She’s forcing his hand and he’s out of excuses. He’ll have to be cruel, present a challenge. Truth or dare. There’s nothing else he can do.

He sighs again. It’s time now to be someone else, someone much, much better than himself, and she’s expecting him. He reaches toward the keyboard and is suddenly startled by a beeping sound and a message flashing red on his screen—one, actually, that he has been waiting for.

He quickly opens a window on another monitor. Aha.

It seems that some jokers have been repeatedly hacking into the new AVAVISNET air traffic control system at O’Hare airport, one of the world’s busiest, just down the road. He’s been remotely monitoring it since he first suspected intruders, and it appears that they’re in there again.

He chuckles softly. These clowns don’t realize that they’re playing with fire; in a very short time thousands of innocent lives will be in jeopardy. There’s a lesson here that they will have to learn. From the master himself.

Chapter Three

“So the girl will be in danger?”

“Considerably,” says Tobor “Toby” O’Brian, nervously kneading his long pale fingers. “I’m afraid there’s no way to avoid it. But, of course, it’s a relatively small price to pay.”

“And Clayborne, too?”

“Yes, yes . . . him, too. What can I say? It’s such a dangerous game.”

O’Brian, director of information systems at AlphaBanc’s enormous McCarthy complex, is speaking to the senior vice president of finance, Edward Van Arp. They are sitting on very soft, very expensive leather chairs in the offices of Karl Bergstrom, president and CEO of AlphaBanc Financial Services. The long walnut table before them is aligned with floor-to-ceiling windows that enclose three walls of the huge office. From the sixty-fourth floor of One AlphaBanc Center, the view is usually stupendous, with the Hancock building, Water Tower Place, and the broad blue expanse of Lake Michigan to the east, and to the west, the complicated gridworks of metro Chicago, sprawling into the great rolling plains of the Midwest.

Today, however, an unusually cool morning in early September, the upper floors of the building are enclosed in fog, and O’Brian and Van Arp float in a vast Olympian whiteness that seems to insulate them from the rest of the gritty business world that grinds below them, far away.

“Toby, Edward, I’m sorry I kept you waiting.” Bergstrom strides through the open double doors that separate his office from the anteroom of his secretaries. He is a tall athletic man with perfectly trimmed silver hair and icy gray eyes that immediately lock on his fellow executives. “Al Sturgis won’t be able to join us; he had something to take care of in New York.

But the others should be here in a few minutes.”

“Okay, Karl,” says O’Brian. “We’re ready.”

“Good. Let me refuel on java here and we’ll get started,” he says, absently fiddling with his heavy gold cufflinks engraved with the AFS logo. “Darryl’s going to give us some sort of super systems demo, I gather.”

“Oh, what’s that about?” asks Van Arp.

“I’m not really sure. Something that only another propeller-head could love,” says Bergstrom, casting a wicked grin toward O’Brian. “You know anything more about this, Toby?”

“Well, actually I do—”

“All he told me was that it was an alternative solution to our problem with Dunne—and that it would knock my socks off!” Bergstrom continues. “Well, I damn well hope so, because we could use a solution about now,” he adds with a sudden frown as he walks out.

“So what’s going on?” Van Arp asks O’Brian. Van Arp, a shorter, less perfected version of Bergstrom, has thinning gray hair and watery blue eyes, upon which he wears contact lenses enhanced with a slight tint which he thinks no one notices. But everyone does, especially O’Brian, a pale lanky man with a dense thatch of wavy dark brown hair, who is used to keeping a keen eye on his computer systems, alert for the slightest blip, blink, or other incongruity in the cyber-status quo.

“Well,” O’Brian sighs deeply, “Gates thinks that we might be able to get along now without Norman Dunne.”

“You’re kidding. So the plan with the girl, Darrow, and with Clayborne in San Francisco is a no-go?”

“No, not at all. But suppose our little trap doesn’t work? Gates is going to give us a demonstration of some super system penetration—supposedly as good as Dunne’s.”

Van Arp sniffs. “Well, all I’ve heard is that Norman Dunne is a genius, absolutely irreplaceable.”

“Well, yes, that’s my opinion, too.”

“What’s Gates think he’s going to do?”

“I don’t want to spoil the surprise. All I can tell you is that I’m not too thrilled with it; I just hope he can pull it off.”

Van Arp looks intently at O’Brian. “Do you think we could actually go it alone? Without Dunne?”

O’Brian shrugs, intertwines his fingers. “With the extremely critical nature and magnitude of this, er, project, and the time constraints we’ve got, I don’t see how it would be possible. No one has ever been as good as he was at compromising supposedly secure systems. And with his, ah, indiscretions, of late—”

“The killings.”

“Yes. Have you seen the pictures of the crime scenes?”

“No, I always seem to be out of town when—”

“Well, here then,” says O’Brian, reaching down to open a briefcase he has under the table. He brings up a thin folder, pulls out several color photographs, pushes them over to Van Arp. The photo on top depicts a horrific scene, the blood-smeared head and upper torso of what had once been an attractive young woman, her throat viciously slashed open.

“Oh my God . . . oh God . . . so this is what he is doing?”

“Yes. That one is frightful. Incredibly bloody . . . but the ones of the garroting are almost worse, I think . . .”

“Oh Jesus. These are disgusting.” He shoves the photos back at O’Brian. “We’ve got to stop him. Now.”

“Yes, you see, that’s why we’ve got to find him and bring him in as soon as possible.”

“I agree completely. The man’s out of control.”

“And yet,” O’Brian smiles ruefully, “we need him now like we’ve never needed him before.”

Chapter Four

The executives have been joined by Darryl Gates, senior vice president and CIO of AlphaBanc’s formidable information technologies area, and Maury Rhodden, a rumpled little fellow who works for Gates as a senior systems engineer. They are all seated around the end of the long table in Bergstrom’s office watching the CEO fitfully pace around the room before he takes his seat at its head. “Okay, let’s go,” he says. “We might as well get started.”

“Say, Karl, wasn’t Pierre going to be here today?” asks Van Arp.

“Well, he said he was going to try to make it—”

“I’m here, I’m here . . .” calls a voice from across the room.

They all turn to see a tall, thin, somewhat stooped elderly man in a black suit fastidiously close the office doors behind him. He looks up and smiles. “Sorry I’m late.”

“Well, Pierre,” Bergstrom smiles, “you know we couldn’t start without you.”

“Bah!” says Dr. Lefebre, adjusting the steel-rimmed glasses perched upon his long Gallic nose. “Sure, sure you couldn’t . . .” he mumbles as he shuffles over to the table.

Bergstrom stands and pulls a chair out for the old man, helps him get seated. “Okay, now we’re ready,” he says, looking over at his CIO.

“All right, Karl,” says Gates, nervously fingering his new electronic wand, a sleek pencil-size remote unit that controls practically everything in the room. “Before we proceed with our little demonstration I want to report to everyone how things are shaping up with our communications grid.”

Gates points the remote toward the back wall and a large dark panel suddenly illuminates and a color animation sequence commences, of the earth surrounded by a spheroidal grid of silvery satellites.

“Uh, is that the latest model, Darryl?” O’Brian asks.

“Hmm? Oh, yes, this is the 5000 series,” he shrugs, flicking the unit, which sends a red laser pointer to the screen. “So . . . now that Datacomsats 28 and 29 are in orbit, the North American communications network is ninety-two percent complete, with the addition of the northern and southern states of Mexico, including, of course, all of Mexico City. But the infrastructure down there is still pretty feeble, and we mostly consider this a future opportunity. Anyway, this will enable us to bring data into the network nearly instantaneously, without having the two to three day wait we had previously.”

“Was it really that long?” asks Van Arp.

“Sure, sometimes even longer. But with the new mainframe we’ve installed here, we’re able to get almost as much processing power as we had previously, when we relied solely on McCarthy.”

“Oh? I didn’t think there was any comparison,” says Van Arp.

“Well there’s really not,” O’Brian chimes in. “For our statistical modeling routines, there’s nothing, actually, that comes close. For sheer horsepower,” O’Brian smiles, finding it difficult to hide the thrill he gets talking about the gigantic supercomputer installed at his McCarthy complex, “there’s nothing on the planet that can compare to the processing power of—the Source.”

Gates winces at the latest name O’Brian has chosen to call the big machine. But maybe that’s an improvement; it used to be the Magic Mountain.

Karl Bergstrom tilts slowly back in his chair, smiles, says softly, “And we’re actually getting there, Grand Unification,” apparently to himself, although everyone at the table hears him and becomes attentive, as they always do whenever the president speaks.

They all understand that he—and each of them—has a right to be proud. Nearly ten years of concentrated effort finally coming to an end. As if basking in their shared thoughts, Bergstrom relaxes somewhat. At sixty-one, he is showing his age, the long days and nights taking their toll around his eyes, but he is still handsome, tall, deeply tanned; he exudes pure CEO—the only thing, with these looks, at his age, he could possibly be in the world. And this upcoming project with Norman Dunne, he and everyone in the room knows, is going to be the capstone of his career. And yet—as they also all know—if all goes well, no one, other than themselves and a small cadre of expendables, will ever know of it.

“Grand Unification . . . bah!” sputters Pierre Lefebre. “Our petty bastardization of Albert Einstein’s name for his noble concept, his great dream. And we are doing this!”

Everyone turns toward Dr. Lefebre and at the same time stifles a smile. Lefebre is nearly eighty, easily the eldest of their group, and is also indisputably the most intellectual among them.

“Well, Pierre, you were in the meeting when we decided upon this project name. In fact,” Bergstrom smiles cagily, “as I recall, you might have come up with it.”

“Me? I—well, perhaps. But now I see all too clearly the dark side of this thing. And it troubles me, Karl. More so than ever before. Einstein—you know I met him once, many years ago at Princeton, of course you do—searched for universal truth, and we are searching for, for what? Wretched, miserable, little beastly details about people’s lives—trivia! And that is not any sort of truth or enlightenment, no beauty to it, none at all—just the opposite, in fact: ugly, sad minutiae, very sad indeed!”

The room falls silent.

Bergstrom grimaces, shakes his head. “Now, Pierre, you know as well as the rest of us what the fruits of our labors will be. Don’t forget that all those, what you call details, in the aggregations that we will be able to produce for the first time in the history of the world, I might add, are extremely valuable, for marketing, for political polling, for crime prevention and the very honorable fight against terrorism—”

“And for governmental domestic spying, corporate espionage, the tracking of humans like they were just so many inventory items . . . the potential abuses are mind-boggling!” Lefebre snaps back.

Bergstrom sighs. “Pierre, you certainly know how to put everything in perspective.” Bergstrom is really the only one who can lock horns with Lefebre. They are very old friends—Lefebre had been his chief mentor in the firm—and Bergstrom knows that whenever the old man goes on like this it is best to simply change the subject. “Well, I happen to think that it’s quite a noble—and extremely profitable—goal. And of course some parts of the project will be more, ah, enjoyable, than others. Now, has everyone seen the dossier on Christin Darrow? She’s a senior financial analyst in mergers, originally from the Seattle branch. There’s a cutie, hey?”

Everyone perks up immediately, including Dr. Lefebre.

“Oh God, yes. That looker in M&A, good choice.”

“She’s the one, all right.”

“Ed always gets the best ones, anyway.”

Van Arp grins. “Well, I understand she’s essential to the, er, plan . . . unfortunately.”

With the addition of this last word, everyone’s smile dissolves, including Van Arp’s.

Bergstrom picks it up again. “Well, it’s nearly eleven. Are we ready to proceed with this demonstration? Darryl?”

“Karl,” says Gates, “we’ve got Richard Clayborne on the line right now. AlphaBanc West. Maybe we should first—”

“Yes,” sighs Bergstrom. “Let’s get him out of the way. Oh, by the way, Zara is going to be out there with him, with Clayborne. She’s heading up this phase of the project.”

“Oh boy,” someone groans.

Bergstrom grins, “Well, we all know she’s damn good, er, at this sort of thing.”

“Amen,” grunts Van Arp.

Everyone chuckles. Gates points the wand across the room and the second panel illuminates, turning deep blue with the golden AFS logo displayed in its center. After a few seconds the logo vanishes, replaced in the upper left hand corner with the legend: SF ACCESS . . . PLEASE WAIT.

“Hmm,” O’Brian mutters, “the satellite link appears to be a little slow this morning . . .”

Just then, the legend appears: SF INTERLINK – ACTIVE, a quick sequence of numbers, the date and military time, then another blink and a menu of approximately twenty names is displayed. The name: Clayborne, R.W., is blinking in green.

Gates flicks his wand again. The screen goes completely black, then reappears, presenting a smiling well-dressed young man sitting attentively before a large bookcase in what everyone in the room recognizes as the library and conference room of AlphaBanc’s San Francisco branch.

Bergstrom clears his throat and speaks, “Clayborne, how are you today?”

“Fine, sir. Thank you.”

“Good. How’s the weather out there?”

“Oh, cool. Foggy today.”

“Here, too. Now, Richard, I guess you know everyone in this room, except perhaps Dr. Lefebre and—”

“Actually, sir, your side of the video link isn’t up.”

“It isn’t? What—?”

Gates and O’Brian immediately lean over to Bergstrom, Gates tapping the mute button on the wand. “Forgot to mention it, Karl. We thought it might be best that he not see us all together on this end. It’s not exactly a normal piece of business he’s about to undertake. This NEXSX thing.”

“Oh, yes. Well, good idea, then.”

Gates taps the mute button again and nods.

“Clayborne,” says Bergstrom, “can you still hear me?”

“Yes sir.”

“The link is temporarily down here, son. Some technical difficulties.”

“Yes sir, I understand.”

“Now, I am told that, aside from your MBA, you hold an undergraduate degree in psychology from the University of Wisconsin. Is that correct?”

“Yes sir. I developed an interest in marketing, the psychology of it, during my time at Wisconsin and went on to pursue it at Northwestern.”

“So, besides your help in setting up this . . . little scheme to locate Dunne, you also understand, on a psychological level, what we want you to do, communications-wise, with Darrow?”

“Yes sir. I do.”

“And you understand that the young woman might be in some danger. And possibly even yourself?”

“Yes sir, although I was assured that you would be constantly monitoring—”

“Oh yes, yes.” Bergstrom glances over at O’Brian and Gates. “Of course, we’ll be on top of everything, but the man we’re after is a genius, a-a demented genius—and that’s why we have to be so careful.”

“I’ve been briefed, Mr. Bergstrom.”

“Good, good. Well, then I guess that’s all we have here. You are to initiate contact fairly soon now, I am told.”

“Yes sir, I’m ready.”

“Good. Well, we’ll sign off here. Good luck, Clayborne.”

“Thank you, sir. Good-bye.”

The red light below the camera lens in San Francisco blinks out and Clayborne loosens his tie, shakes his head. “Damn this old system!” he mutters. “I didn’t even get to see them . . . but at least they could see me.” Which he considers much more important, but still frustrating. He gently whacks the side of the monitor as he gets up. A piece of junk. There always seems to be some kind of problem with it. He’s about to power it off when he hears Karl Bergstrom’s voice coming through the speakers: “Do you think Clayborne’s in any real danger?”

“Not really. The Gnome only goes after women, you know, lovely young women,” says a voice he thinks might be O’Brian’s. Clayborne looks up at the unit’s camera; the little red light is still out. It appears they can’t see him, and most likely have no idea he is still on the line.

“Like our Miss Darrow.” Bergstrom’s voice is quieter now.

“Yes, our little Miss Christin.”

“Bait. Gnome-bait. Jesus, it’s ugly.”

“Does Clayborne know about the murders?”

“No. They’ve been in the news, of course. Locally, here. Unsolved. No one knows that Dunne is involved but us.”

Oho. Murders, thinks Clayborne. Now the evil message he had received made some sense. That bloody photo of a young woman was the victim of a slasher. Who now apparently seems to be Norman Dunne, the Gnome. A gruesome serial killer? This is what they are hiding from him? He continues to listen.

“So Clayborne knows nothing about them? The murders?”

“That’s right. We only told him that Dunne has stolen some of our data and that he might be dangerous. Not how dangerous. Clayborne’s PERSPROF indicates he might be a person of some integrity. We think he’s presently quite loyal, but we don’t want him to get weird on us. Go outside or something.”

Clayborne’s ears burn. Might be a person of integrity? Well, maybe they’d better take another look at their idiot PERSPROF, which is of course AlphaBanc’s infamous statistically correct personality profile whom every AlphaBanc employee has lurking within their online personnel file. And why would he go “outside?” Where exactly is that?

It’s extremely risky, but in the most daring decision he has made thus far in his carefully cultivated career, he decides to continue eavesdropping. He’s just got to know what’s going on.

We’re excited to announce a brand new Science Fiction Book of the Month here at Kindle Nation, to sponsor all the great bargains on our Science Fiction search pages.

Thousands of Kindle Nation citizens are using our magical search tools to find great reading in the Free, Quality 99-Centers, and Kindle Lending Library categories. Just use these links to search for great Science Fiction titles:

And while you’re looking for your next great read, please don’t overlook our brand new Sci Fi Book of the Month!

by Andrez Bergen

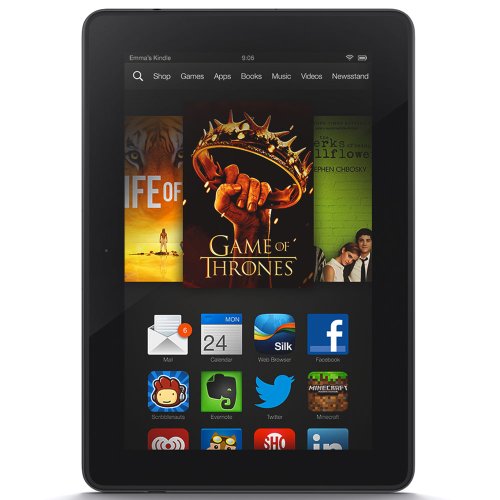

Gift Alert! This could be the last chance before Christmas to save this much on a

Kindle Fire HDX 7″, HDX Display, Wi-Fi, 16 GB

Kindle Fire HDX 7″, HDX Display, Wi-Fi, 16 GB

Kindle Fire HDX 7″, HDX Display, Wi-Fi, 16 GB

Today’s Bargain Price: $183.20

Free Books! Download Now While Still Free

★★★★★

Nine Bestselling Freebies Plus The Best Kindle Deals & Steals

Today’s Kindle Bargain: Deanna Lynn Sletten’s Sara’s Promise (99 Cents)

Deanna Lynn Sletten writes women's fiction and romance novels that dig deeply into the lives of the characters, giving the reader an in-depth look into their hearts and souls. She has also written one middle-grade novel that takes you on the adventure of a lifetime.

Deanna's romance novel, Memories, was a semifinalist in The Kindle Book Review's Best Indie Books of 2012. Her novel, Sara's Promise, was a semifinalist in The Kindle Book Review's Best Indie Books of 2013 and a finalist in the 2013 National Indie Excellence Book Awards.

Deanna is married and has two grown children. When not writing, she enjoys walking the wooded trails around her northern Minnesota home with her beautiful Australian Shepherd or relaxing in the boat on the lake in the summer.

Deanna Lynn Sletten writes women's fiction and romance novels that dig deeply into the lives of the characters, giving the reader an in-depth look into their hearts and souls. She has also written one middle-grade novel that takes you on the adventure of a lifetime.

Deanna's romance novel, Memories, was a semifinalist in The Kindle Book Review's Best Indie Books of 2012. Her novel, Sara's Promise, was a semifinalist in The Kindle Book Review's Best Indie Books of 2013 and a finalist in the 2013 National Indie Excellence Book Awards.

Deanna is married and has two grown children. When not writing, she enjoys walking the wooded trails around her northern Minnesota home with her beautiful Australian Shepherd or relaxing in the boat on the lake in the summer.Prices may change at any moment, so always check the price before you buy! This post is dated Monday, December 9, 2013, and the titles mentioned here may remain free only until midnight PST tonight.

Please note: References to prices on this website refer to prices on the main Amazon.com website for US customers. Prices will vary for readers located outside the US, and even for US customers, prices may change at any time. Always check the price on Amazon before making a purchase.

by Colin F. Barnes

by William Irwin

Behind the cool costumes, special powers, and unflagging determination to fight evil you’ll find fascinating philosophical questions and concerns deep in the hearts and minds of your favorite comic book heroes.

by Oscar Wilde

by Carolyn Marsden

by Elise Logan, Emily Ryan-Davis

by Mark Berent

by Susanne O’Leary

by Katherine Kingsley

“A challenging and fascinating addition to the science/religion dialogue…”

In ETERNITY —

a bold new exploration of age-old questions — one scientist’s odyssey in the laboratory brings illuminating insights into religion.

by Trevelyan

The creation of a zone of Eternity, a space without time, in the laboratory was regarded as so outrageous that almost the entire physics community is in a state of denial about the outcome. Eternity is a prediction of traditional theology, dating as far back as Plato and Saint Augustine. Having a laboratory model enables these philosophical ideas to be tested against experimental reality. The implications for the relationship of a creator God to the creation are profound.

A further shakeup to our understanding of reality was delivered recently, when quantum mechanics was derived from the mathematical principles of information theory. The ancient notion of a universe made from the stuff of ideas suddenly leapt into plausibility. Examining the concepts of the soul, and the puzzle of good and evil, from this perspective brings us to a coherent picture of reality in which science and religion sit as comfortable partners, the two sides of the same coin.

This book is written for a lay readership: despite the profound questions being addressed, no detailed knowledge is assumed beyond a broad familiarity with high-school science. There are however, some who should NOT read this work: they include religious fundamentalists and biblical literalists who deny science, and also those scientifically-minded people who consider religion only applicable to matters science is unable to explain {the “god-of-the-gaps” idea}. Science is now able to offer spectacular illumination of religious and philosophical concepts.

Praise from Amazon readers:

“I very much enjoyed the easy-to-read writing style, which is a little like listening to a good lecture…The science in the book is very well explained and…The book also explores …what the major religious traditions have to say about the big questions of our existence. This is then linked in nicely to the discussion of what science can say about those same questions…”

an excerpt from

Eternity:

God, Soul, New Physics

by Trevelyan

Chapter 1: Overview

Consider the following propositions. Eternity, the theological construct of space without time, can now be produced in the laboratory. The soul, which has a quantifiable, physical nature, is compatible with Eternity. The physics of time proves that a creator God must be outside of time, bringing time into being with the universe, rather than initiating a universe at a particular point in pre-existing space and time.

Are these ideas speculation, fantasy, or science fiction? … No, this is hard-nosed, down-to-earth science: the results of experiments with machines made of metal, glass and electronics.

Ideas which have puzzled the greatest thinkers since the dawn of history are now amenable to analysis, thanks to advances in physical science which are so recent, so inflammatory – regarded by many as so outrageous – that hardly anyone has yet fully understood them. Instead of science demolishing religious philosophy, it suddenly shows that the philosophers were in so many ways on the right track all along, but simply didn’t have the language, let alone the technology, to progress their thinking.

These advances now make explicit three concepts which have traditionally resided in the far reaches of obscurity: Eternity, the soul, and the ultimate nature of reality – the structure lying beneath the waves and particles of subatomic physics. Religious philosophy is changed, focused, clarified by these insights. No longer do we merely speculate, or have to satisfy ourselves with the words of ancient prophets. We have answers.

The journey to this insight is demanding. This book is 78,000 words and spans theology and religion, relativity, quantum mechanics, the neuroscience of the mind and the theory of information. If it were presented like a detective novel – fact after fact, puzzle after puzzle, hoping it all comes together in the end – the challenge to the reader’s stamina would be daunting.

Instead therefore, we will lay out the conclusions up front, painting the picture with only the broadest of brushstrokes. This strategy is regularly employed by historians and philosophers, rendering their weighty tomes accessible to the reader. Such an introduction, with the arguments in skeletal form and no flesh on the bones, cannot be persuasive in any scholarly sense. Rather, it serves to indicate the paths that will be taken and the territory to be covered on the march towards our final goal.

Come with me on this journey. I promise we can explain the physical science without bogging down in algebra, just as we will avoid the impenetrable undergrowth of polysyllabic neologisms which clog the literature of philosophy and theology. Let’s get started…

God is outside of Time

Four centuries before Christ, the Greek philosopher Plato argued that time was created with the universe, rather than the universe being created at an arbitrary point in pre-existing time [Timaeus 37d]. For Plato, time was the moving image of Eternity, and Eternity – a timeless state – was the domain of God.

The Christian theologian of the 5th century, Augustine of Hippo (Saint Augustine), elaborated on this idea in his mighty work Confessions [Book XI]. In Eternity, God could not experience a flow of time. God must be outside of time.

This conclusion, actively debated but broadly accepted by philosophers and theologians down the centuries, was based on logic and reason alone.

Today, we have laboratory data. Any rational conception of a creator, or a process of creation, must be placed outside of time. The proposition does not depend upon any particular religious tradition or conception of deity. It is an experimental result.

When I mention this in conversation, many people become indignant, telling me I am completely insane because we cannot do experiments on God. I have to remind them there are two nouns in the proposition – God and time. We can experiment on time. Once we have the results, we see that any conception of God must place the creator outside the construct of time. Whether you have an anthropomorphic picture of deity, or a highly abstract concept akin to the summation of the mathematical laws running the universe, or anything in between – the conclusion is the same. Even the most committed atheist, looking at the evidence, would concede that the process of creation (even if there is no creator) lies outside of time.

This often takes a moment to digest. Then the response is on occasion quite angry, asserting that time is absolute, marching on unaffected by anything that could be done in a laboratory or by any contrivance of human ingenuity.

I point out that this view is incorrect, and that we have known it is wrong for more than a hundred years.

Time can in fact be speeded up or slowed down simply by climbing a mountain or going down a mine-shaft or taking a ride on a rocket to the International Space Station and back. Clocks precise enough to show these distortions are commonplace pieces of lab gear. The GPS which you use to navigate your car depends on accurate clocks in the satellites. If these were not corrected for the effects of height and speed, the GPS frame would accumulate errors at about 12 kilometers (7 miles) per day. Time is affected by gravity and by movement. This is not high-flown theory: these days, it is simply practical engineering.

Some people – mercifully – are stopped dead in their tracks by this revelation. Others, more secure in their superstitions, look at me pityingly and intone, “Time has NOTHING to do with clocks.”

This jaw-dropper is surprisingly common. But, of course, it couldn’t be more wrong. Everything we know about time, everything we can know, is about clocks. Time is physics; physics is measurement; and clocks are the instruments that measure time. Once we understand the physics of time, a topic we take up in Chapter 2, we come to realize there is nothing more to know about time than a complete understanding of clocks.

Eternity is Timeless

Practically everyone I talk with thinks Eternity means an infinity of time: time without end, time going on forever.

Even dictionaries include this definition. But it is a slip in the meaning of the word, a loss of precision in our language. The original sense was quite different.

Eternity is a concept first developed by philosophers and theologians, long, long ago. We are back with Plato, Aristotle and Augustine.

Visualize a void, without matter, without the created universe. To the theologian, this would be the domain of God, the Creator without His creation. Would it have time?

Philosophers said no. Eternity, they reasoned, must be a timeless state.

In Eternity, there is no change, no process, no cause and effect, no tick of a clock to mark the passing of the hours. Change, in Eternity, is impossible. A clock, therefore, would not tick: hands would not move; mechanisms would not work. In Eternity, time simply does not exist.

For over two thousand years, this concept was merely an abstraction. Now today, in laboratory experiments, we can make a tiny zone of Eternity: we can create a space without time, a space in which clocks freeze.

The story begins with an anomalous result in the laboratory of Professor Gunter Nimtz and colleagues at the University of Cologne back in the 1990s. The picture grew in solidity and detail over succeeding years as lab after lab picked up the idea. Waves crossing barriers which they do not seem to have enough energy to cross – the phenomenon of quantum tunneling – exist in a timeless state inside the barrier.

Bitter controversy grew as the data were seen to challenge one of the most respected deductions of Relativity Theory: the impossibility of signals exceeding the speed of light in a vacuum. This dispute came to dominate the discussion among the physics community.

Far more interesting from a philosophical viewpoint, however, is the laboratory model of Eternity provided by an appropriate configuration of this type of experiment. The model, of course, works only with electromagnetic waves: light, microwaves, radio, etc. But it provides striking results, a practical implementation of what had, for millennia, been seen purely as philosophical speculation.

Today, we can make Eternity in the lab. Study it. Measure it. Understand its physics.

The implications for theology are profound. Eternity is the domain of God. Eternity is the realm of souls. Eternity is the perspective from which God views the world. And now able to test samples of it in the lab, we can bring evidence – rather than mere conjecture – to our contemplation of Eternity. We dissect these ideas in Chapter 5.

The Soul is Physical

The notion of the soul having a physical reality seems an outrageous proposition. To many of us, the defining characteristic of the soul is that it is not physical, that it stands distinct from the mortal flesh of the body. From the dawn of history, a recurring concept in human cultures has been the notion of an abstract essence which encapsulates the individuality, the morality, the thoughts, deeds and worth of a human being.

To pick this idea apart, let us take a less emotive example: an abstraction, which does not at first sight appear physical, but which pairs with a physical object.

The physical object is a book. The hardback version is solid and substantial: drop it on your foot and it hurts. Yet we immediately know there is an immaterial essence to it. As well as the hardback, the same book is available as a paperback, an audio tape, a CD, and even as a Kindle edition, where it is downloaded to your reader as a computer file.

In all these different forms, however, we have the same book, the same story, the same narrative that we could relate verbally around a campfire or recite to the children at bedtime.

This abstract essence – which is preserved across the range of physical forms and is therefore in a sense independent of the physical implementation – is undeniably real. It is well understood in contemporary science and technology. It has a mathematical theory: a set of theorems and rules telling us how it can be transmitted, received, stored, retrieved and measured. This essence is called, of course, information.

In the contemporary world, information technology is ubiquitous. We forget that the underlying science is little more than half a century old, beginning with the work of the American engineer, Claude Shannon, at the Bell Laboratories in 1948. The senior generation alive today grew up in a world where there was no information technology, no mathematics of information, no relevant theory. The word information meant, in that era, simply knowledge, or perhaps data. There was no inkling of the sense we have today, where information is measured in bits and bytes, and everyone understands why it will take longer to download a movie than song. In the youth of our grandparents, the statement that a lengthy novel was about a megabyte would have evoked nothing more than blank stares.

For over two millennia, philosophers and theologians have debated the nature of the soul. Without a theory of information, they have accumulated a vast amount of intellectual baggage, while comprehensively missing the essential insight.

Today, science fiction writers discuss a form of immortality to be achieved by uploading the mind into a virtual reality, or perhaps into a computer-controlled robot. Imagine you were facing untimely death from an incurable disease. In this scenario, you might be saved through high-tech brain scanning, uploading your essence from your biological body into the technological hardware.

Philosophers have taken up this theme as a model for understanding the essence of sentient, conscious beings. In principle – though it lies far beyond our technological reach and would invoke a whole raft of ethical problems – the idea seems a rational possibility. The philosophical value of debating the concept is that it forces us to focus on exactly what it is that we would be preserving by such an intervention.

If the causal structure of your brain’s processing circuitry and memory were faithfully copied in the uploading, you would believe that you were still you. If your friends and family were similarly uploaded, you would react to them in precisely the same way as you did in your previous existence in the real world. Almost everyone who has thought about this idea agrees: you could in principle live on in a robot, or inside a virtual world, exactly as you do in a normal, mortal life.

And what is it that passes along the cable connecting the scanner analyzing your biological brain with the computer driving the robot or implementing the virtual world? It is information: bits and bytes.

Only the most dogged of religious fundamentalists deny the implications of this. The life continuing on in the robot or the virtual reality is not a soulless specter. It is you, just as you were: a moral agent exercising freewill, doing good or evil by choice according to your values and convictions. At the moment of transfer of your life from the real to the virtual, your soul will not depart for heaven or hell, plucked out from the dying body by a peevish God who would have nothing to do with virtual worlds. If God smiled upon us when we invented fire to cook food, metal to make tools and medicines to heal the sick, then surely He will approve when eventually we can free ourselves from the shackles of mortal flesh.

The implication is clear. The essence of your being is information. It is an abstraction, able to be preserved in a variety of different physical forms and therefore having a degree of independence from the material world. Its match to the traditional understanding of the soul is compelling.

Once you have grasped this idea, it seems fairly self-evident. Yet philosophers and theologians, weighted down by the ballast of their 2,400 years of baggage from debating the nature of the soul in an information-theoretic vacuum, have yet to embrace the conception. Information theory is studied by engineers and mathematicians. It is little known among philosophers, even less among theologians.

There is one more step which the physics enables us to take. We can show, in the laboratory, that information is compatible with Eternity. This is a surprising result, because Eternity, being without time, must be without energy. Nevertheless, we can transmit information (in the form of a stream of bits) into the zone of Eternity in our laboratory model – and recover that information intact, on the far side of the zone.

The theological implication is clear: the physics is telling us that information, the stuff of souls, is compatible with Eternity, the domain of God.

We take up these issues in detail in Chapter 6.

The Foundations of Reality

Our attempts to understand nature have for millennia been plagued by dualism: the notion that any complete description of reality must contain pairs of distinct and mutually-irreducible elements.

Plato contrasted forms (ideas, abstractions) with matter (the solid material of the visible world). Aristotle wrestled with several dualities: body and soul, matter and form, the material and the immaterial. The 17th century French philosopher, Rene Descartes, formulated a concept of a mind–body dualism which gave primacy to the mind [Cogito, ergo sum: I think, therefore I am].

Even in the contemporary world, where science ranges from subatomic particles to the far reaches of the cosmos, the dualism between information and matter seems stubbornly irreducible. To describe knowledge – which guides our actions and can be reproduced by students in examinations – merely as the state of trillions of synapses in the brain, seems to miss something essential.

If the material world of matter and energy is all that exists, we lack an adequate picture of the informational domain: the abstract forms of Plato, the mind in psychology, the soul of religion. Knowing the mathematics of information theory does not remove the ache… we remain stuck with the dualism.

The failure to explain the abstract in terms of conceptions rooted solely in the material world, prompts us to toy with the idea of reversing the paradigm. Could the abstract in fact be primary, and the material world be somehow derivative? Can the ancient philosophical position of idealism rescue us from our dilemma?

Common sense rejects such a notion out of hand. How can a solid object, like a table for example, be built from the stuff of ideas?

But quantum mechanics, the spectacularly successful theory which underlies most of the technological innovations of the 20th century, suggests the concept is far more credible than it first appears. The visionary American physicist, John Wheeler, coined the memorably arcane phrase it from bit as shorthand for this view. Instead of thinking of subatomic particles as bundles of waves and energy, we instead see them as packets of bits: information as we are familiar with it in contemporary technology.

Recent work on the theoretical foundations of quantum mechanics, inspired by progress in quantum computing, has taken a dramatic step towards validation of this idea. Quantum theory – which had always lacked a sound conceptual foundation, being essentially a rag-bag of math plucked out of the air to match experimental results – can now be derived from a compact set of logical postulates. The deeper foundation lying beneath quantum mechanics turns out to be information theory.

Dualism has been with us for more than 2000 years. Abstractions like ideas, knowledge and mathematics seem to exist in a different plane from the mundane reality of matter and energy, space and time. But now, suddenly, our picture turns around. It is not ideas and the soul which are chimeras, illusions we create in our endless search for meaning. Reality itself is the illusion. Atoms and molecules, tables and chairs, stars and galaxies are all a construct of the one deeper reality: information itself – the stuff of souls.

The Measure of Good and Evil

Armed with insight into the nature of the mind, the soul and even matter itself, we are ready to make a leap of inductive logic and clarify the previously intractable problem of good and evil.

No longer must we retreat to moral relativism or seek refuge in the dogmatism of revealed religion. With souls and the material world composed of the same physical essence, good and evil snap into focus as constructive or destructive influences, which can be measured by the change in the information content of minds, souls and entire cultures.

Such a measure is absolute. It is not subject to arbitrary reversal in the various moral frameworks of different ethnic and religious groups, but instead enables good and evil to be unambiguously identified.

Many readers will find the concept of justifying moral absolutism on the basis of mathematics even more challenging than the physicality of the soul, or the realization that we can learn about Eternity and God in the laboratory rather than from the pages of a Bible. Hang on for a bumpy ride!

The Task

Let me be explicit about what this book will do, and what it won’t do.

Being neither a shrill denunciation of the simplistic ideas of ancient prophets, nor a rearguard action defending religion against the encroachments of science, this work instead applies advances in modern physics to age-old questions about the ultimate nature of reality, the relationship of a creator to the creation, and the physical nature of the abstract essence of human life, traditionally called the soul.

The book is written for a general audience: readers with a curiosity about religion and science, but with no specialist training in either discipline. Like the popular magazines New Scientist and Scientific American, we will assume a broad familiarity with science at high-school level, without demanding recall of any specific detail. Because the book covers such a wide range of topics, from relativity and quantum mechanics to neuroscience and theology, readers with specialist knowledge in some areas may still gain useful insights in others if they are prepared to skim quickly over material they find too elementary.

We will take as a given the principle that religious thought has something to offer on our path to a comprehensive appreciation of reality, life, purpose, morality and meaning. Science is very good at answering the kinds of questions that science asks: matters arising from the empirical domain of observation, experiment and theoretical interpretation. It is not so good at addressing the subjectivist domain of meaning and moral value: matters for philosophy, ethics and religion.

Recognizing this dichotomy, however, does not mean that we reject the parallels between scientific and religious modes of thought, parallels which the British priest and physicist, John Polkinghorne (recipient of the 2002 Templeton Prize), has explored in his many books. Indeed, it is only by utilizing both modes of thought that we gain well-rounded insight.

Many of the popular books on the science-religion dialog are authored by physicists. Not surprisingly, their major concern is cosmology. They seek a mechanism by which the universe can be self-starting, at the same time as so incredibly bio-friendly that life was certain to evolve on wet rocky planets, without needing a creator God to fine-tune the environment by purposeful adjustment of physical constants. The latest fashion is to invoke speculative ideas from String Theory to postulate a multitude of “something from nothing” universes [Stephen Hawking: The Grand Design, 2010; Lawrence M Krauss: A Universe from Nothing, 2012].

But as Paul Davies [Templeton Prize winner, 1995, and best-selling author of over 20 books including The Mind of God, 1992] points out, this idea comes with a lot of baggage. It needs a pre-existing space to host a multitude of Big Bangs, and over-arching physical laws to trigger the bangs and populate the emerging universes with fields and forces to produce matter and make things happen. Where did all this elaborate machinery come from? Many would see this as no more than pushing an intelligent choice by a Creator a step or two further back.

We will need to take note of this debate if we are to provide a well-rounded picture of present-day science. But the major focus of the book you are reading is not so much on the origin of our universe, as on what it is ultimately made from. Matter and energy, particles and waves, simply don’t cut it as a complete description of reality. If we limit ourselves to such a materialist picture, we have to relegate abstractions like information (knowledge and ideas) to subordinate status as “emergent properties” of systems. The abstract realm of mathematical theorems and physical laws has to stand apart from the world of matter and energy. A better formulation comes from reversing the paradigm, from placing information at the foundation of the hierarchy.

The final thesis developed at the conclusion of this book is admittedly a leap: a leap of scientific induction. Threads from philosophy, neuroscience, information theory and quantum physics all converge on a conceptual formulation which unifies the physics of the material universe with the abstract world of ideas. Everything – from waves and particles, matter and energy, to the laws of physics and the intricacies of mathematical theorems – are of a single essence.

The validity of the thesis is not demonstrated by a single proof, a dramatic experiment, or progress in any one field of science. Rather, the strength of the idea comes from the convergence of plausible ideas and tentative advances from a number of widely separated fields.

Putting this range of material together into a coherent whole has been a daunting task. Your author’s qualification for this assignment is as a generalist, working from the perspective of fifty years teaching experience. While trapped on the treadmill of university life, my lecturing ranged over basic medical science, clinical skills and applied physics. Since retiring from full-time employment, my research activities have shifted from cellular biophysics to the foundations of Relativity.

The stimulus for tackling this book was my work on the highly technical topic of evanescent fields. It convinced me we had a laboratory model for the theological concept of Eternity, a space without time. The physics community has totally missed this implication, seeing the experimental data from several laboratories as a challenge to the sacred cow of Special Relativity. The results, in fact, do not invalidate relativity, though you need a fairly sophisticated understanding to see why that is so, and to appreciate what they really mean. The important message turns out to be more theological than physical. And since physics journals will not publish anything that smacks of religion, a book was my only option.

Chapter List:

2: Time, God and Relativity

3: The History of Religion

4: Religion in the Modern World

5: Eternity

6: Information, the Essence of the Soul

7: Reality and the Quantum

Chapter 8: Conclusions

The dialog between science and religion is by no means new and a steady stream of books continues to be published on the theme. For a brief review of the state of scholarship on many of the issues, the multi-author compendium, A Science and Religion Primer (2009) edited by HA Campbell and H Looy, is available in a Kindle edition and has much to recommend it. The curious fact, however, is that such works are universally an exposition of problems, with hardly ever a firm conclusion being delivered on any topic.

The book you have just labored through is unusual in that it reaches a significant number of conclusions. These follow from pursuing the logic of advances in physical science: advances which are too controversial for physicists to have absorbed their impact and too recent for philosophers and theologians, by and large, even to be aware of their existence.

The nature of the material dictates that these discussions are confined to plausibility arguments, rather than anything approaching proof. The strength of the conclusions stems from the convergence of several threads of evidence towards a common theme.

The recent insights into the foundations of quantum mechanics reveal information as the fundamental essence of reality, abolishing the dualism of mind and matter. Information is the substratum of space, time, matter and energy. We can make a convincing case for its being the essence of the soul, and the measure of good and evil. Consciousness, a longstanding mystery, can now be seen as an inevitable consequence of information processing within the brain, the hardware implementing the mind. Physics, at every level from the sub-atomic to the cosmological, can be seen as information processing: even suggesting that the cosmos as a whole is conscious.

Physical science began to have an impact upon religious thought early in the 20th century, when Special Relativity demolished our naturalistic conceptions of space and time. Simultaneity – a universal “now” – was invalidated. A creator God who remains involved with the ongoing evolution of His creation cannot have a human perspective on space and time, tied as such a perspective must be to a single inertial frame of reference.

The recent laboratory demonstration of space without time demands that a construct which originated in theology and philosophy – Eternity – be considered as a realistic option in physics. In particular, it must impact on our efforts to understand the origins of our universe. The quantum mechanical solution to the problem of the singularity at the origin of the Big Bang [Hartle-Hawking state] is harmonious with the emergence of our familiar 3+1 dimensional space-time from a timeless space. This places a traditional theological conception on a describable physical footing: a creator God, residing in Eternity and therefore without beginning or end, can initiate a universe of finite age, and in the process create time.

Recognizing information as the ultimate essence of reality not only abolishes dualism in the Platonic and Cartesian senses, but brings physical reasoning to the discussion of concepts which were traditionally viewed in terms far removed from fundamental physics: the soul, consciousness, and good versus evil.

Few authors have had the courage to debate the physicality of the soul. Many dodge the issue entirely by assuming that a defining characteristic of the soul is that it is non-physical, thereby immediately precluding the application of scientific thought-forms to the problem. In fact, the physical nature of the soul is fairly self-evident: it is information.

Information has no mass or energy, but is physically measurable. Experiment shows that information is compatible with Eternity: it can be transmitted into a timeless zone and recovered, intact. This provides another thread of physical plausibility for a religious concept: souls are compatible with Eternity, the timeless domain of God.

The notion of life recorded in a book is a powerful analogy to Eternity. A book does not change: in that sense it is eternal, and yet it records time sequences. The Holographic Principle, applied to the cosmological horizon, shows that the information in our universe maps onto a 2-dimensional surface – like a single page of a book. With a third spatial dimension mapping successive time slices in the evolution of our universe, we add pages. A Book of Eternity, itself timeless, could contain the entire history of our space-time.

The realization that information lies at the core of our being prompts the formulation of a hypothesis about the nature of good and evil. This gives a physical basis for a concept which had previously been seen only in terms of concordance with cultural norms or with the canons of revealed religion. The measure – the information content of individual minds and the culture as a whole – is absolute. Cultural relativism is thereby demolished. An evil practice – evil because it is destructive – can no longer be justified because it is “culturally appropriate.”

The moral absolutism introduced by this physical metric will be condemned in the most furious terms by vested interests, particularly the “intellectuals” who defend the indefensible. The metric is not a construct of Western ideological supremacy, or Christian parochialism, but simply mathematical physics. It happens to match the intuitive concepts of good and evil very well indeed.

Cultural relativists and social theorists will burn the midnight oil in an effort to demolish the dangerous notion of an absolute basis for right and wrong, good and evil. Do not be distracted by counter-examples which reveal only imperfections in the logic of language. Your visceral revulsion at the abuse of women and children, at the persecution of minorities and wholesale denial of civil rights by oppressive regimes, is not merely intolerance of differences or distrust of alien ways of life. Rather it is the biological manifestation of a principle lying at the very foundations of physical existence.

In our search for God, the most harmonious accommodation between scientific and religious views is the theological construct of pantheism (or panentheism). If God is in everything, surely we can search for Him in the foundations of physics, rather than confining our inquiry to scripture based on the ancient and manifestly inadequate worldview of long-dead prophets.

Our efforts to find a Cosmic Consciousness, the transcendent Mind represented in the belief systems of almost all human cultures, can be guided by analysis of our own human consciousness. The postulate that consciousness is an inevitable manifestation of information processing is elevated from plausible hypothesis to intellectually compelling concept by the insight that information lies at the foundations of reality. I think, therefore I am, becomes I process information, therefore I am conscious.

And since the elementary workings of the universe, quantum physics, can be viewed as information processing, it follows that all large networks of causally connected events are conscious – including the universe as a whole.

When we, as sentient beings, stand in awe of the wonder of nature, we have an overwhelming sense of a Presence, a conscious awareness on a cosmic scale. We now understand such a consciousness is implicit in the growing inventory of information and its processing at all levels from subatomic particles to the large-scale structure of the cosmos. This, surely, is the physical basis of the universal instinct upon which we build our religious beliefs.

Traditional religion insists that we cannot look to Nature for enlightenment, but must seek it exclusively within the revelations of scripture.

Yet science shows us a universe of subtlety, intricacy and beauty, rich in purpose. And if we have the courage to look beyond the simplistic views thundered from pulpits and the primitive conceptions of ancient prophets, to analyze reality with minds enlightened by knowledge and reason, we see God right before us. Not as a glorious king on a golden throne aloof from the travails of humanity. Not as a remote, abstract force, a ruler of mathematical laws from which Nature evolves, indifferent to our sufferings. But as a transcendent Mind, interwoven with all of reality. This is the God of science, the pantheistic God, the God who suffers with us.

Sir James Jeans was correct in his visionary concept that the universe is not a grand machine, but rather it is a majestic thought. The laws of physics are not separate from the matter they govern. At the end of the explanatory chain, laws and matter are of the same essence. Rather than being an emergent property, information is the ultimate substrate of reality, out of which emerge matter and energy, space and time.

Our universe is made from the stuff of souls.

We are but a thought in the mind of God.

… Continued…

Download the entire book now to continue reading on Kindle!