Netflix and Martin Scorsese are making their biggest bets ever on the confessions of a mafia “hitman.” The guy probably made it all up. Bill Tonelli from Slate reports on the lies of The Irishman… Support our news coverage by subscribing to our Kindle Nation Daily Digest. Joining is free right now!

Assuming you were alive in April 1972 and old enough to cross the street by yourself, you could take credit for the spectacular murder of mobster Crazy Joe Gallo—gunned down during his own birthday party at Umberto’s Clam House in Little Italy—and nobody could prove you didn’t do it.

Of course, anyone who knows anything about New York City organized crime can tell you who was behind it: The murder was payback for an equally brazen shooting—in broad daylight, in midtown Manhattan—of mob boss Joseph A. Colombo Sr. a year earlier, an attack Gallo supposedly ordered (though even that no one can say with absolute certainty, since the shooter was shot dead on the spot). But no one has ever been arrested or charged in Crazy Joe’s killing, and so technically it’s still unsolved.

The same is true about the disappearance, in July 1975, of Teamsters’ union legend Jimmy Hoffa. He had made some lethal enemies in the mob. After serving a prison term, he persisted in trying to regain control of the union even after he was warned, over and over, to back off. The last time anybody saw him, he was standing outside a restaurant in the suburbs of Detroit, waiting to be driven to what he believed would be a peace meeting. The FBI and investigative reporters have devoted decades of effort to solving the mystery, but all we have is guesswork and theories. So if you want to step up now and say you whacked him, be my guest.

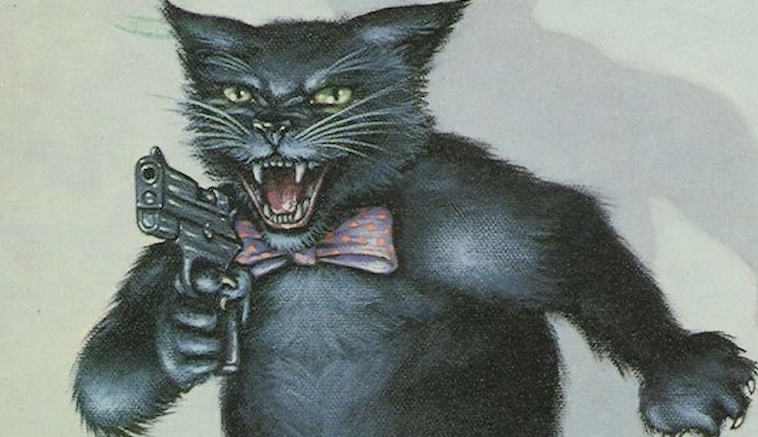

That’s the thing about these gangland slayings: When done properly, you’re not supposed to know who did them. They’re planned and carried out to surprise the victim and confound the authorities. Eyewitnesses, if there are any, prove reluctant to speak up. And nobody ever confesses, unless it’s to win easy treatment from law enforcement in exchange for ratting on other, more important mobsters. Those cases often turn into the ultimate public confessional—the as-told-to, every-gory-detail, my-life-in-crime book deal. Followed by—if you’re a really lucky lowlife—the movie version that fixes your place forever in the gangster hall of fame.

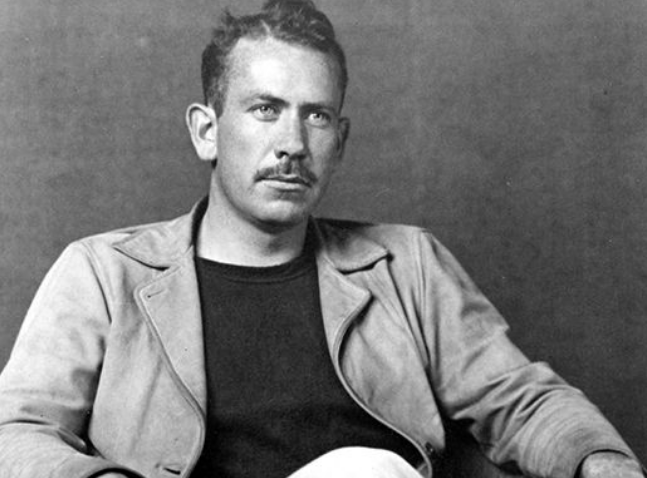

And then there’s the strange case of Frank Sheeran.

Only if you had been paying close attention to the exploits of the South Philadelphia mafia back in its glory days (the second half of the 20th century) might you have noticed Sheeran’s existence. Even there he was a second-stringer—a local Teamsters union official, meaning he was completely crooked, who hung around with mobsters, especially Russell Bufalino, a boss from backwater Scranton, Pennsylvania. Sheeran was Irish, which limited any Cosa Nostra career ambitions he might have had, and so he seemed to be just a 6-foot-4, 250-pound gorilla with a dream. He died in obscurity, in a nursing home, in 2003.

Then, six months later, a small publishing house in Hanover, New Hampshire, unleashed a shocker titled I Heard You Paint Houses. It was written by Charles Brandt, a medical malpractice lawyer who had helped Sheeran win early parole from prison, due to poor health, at age 71. Starting not long after that, Brandt wrote, Sheeran, nearing the end of his life, began confessing incredible secrets he had kept for decades, revealing that—far from being a bit player—he was actually the unseen figure behind some of the biggest mafia murders of all time.

Frank Sheeran said he killed Jimmy Hoffa.

He said he killed Joey Gallo, too.

And he said he did some other really bad things nearly as incredible.

Most amazingly, Sheeran did all that without ever being arrested, charged, or even suspected of those crimes by any law enforcement agency, even though officials were presumably watching him for most of his adult life. To call him the Forrest Gump of organized crime scarcely does him justice. In all the history of the mafia in America or anywhere else, really, nobody even comes close.

Now, though, Frank Sheeran is finally going to get his due.

When it premieres at the New York Film Festival in September before a fall release, The Irishman (as the tale has been retitled) will immediately enter mob movie Valhalla: Martin Scorsese directing, Robert De Niro as Sheeran, Al Pacino as Hoffa, and Joe Pesci as Bufalino, all together for the first (and probably last) time. Sheeran is a part that De Niro has reportedly wanted to play since Brandt’s book came to his attention over a decade ago. The actor has been nursing it along ever since, finally getting Netflix to put up a reported $160 million. This will be Scorsese’s most expensive film ever, in part because of the extensive digital manipulation required to allow De Niro, who turns 76 this month, to play Sheeran from his prime hoodlum years until his death at age 83.

All in all, an astounding saga. Almost too good to be true.

No, let’s say it: too good to be true.

I’m telling you, he’s full of shit!” This is a retired contemporary of Sheeran’s, a fellow Irishman from Philadelphia named John Carlyle Berkery, who allegedly headed the city’s Irish mob for 20 years and had many close mafia connections. Berkery is a local legend, one of the few figures of that era still alive, not incarcerated, and in full possession of his wits. “Frank Sheeran never killed a fly,” he says. “The only things he ever killed were countless jugs of red wine. You could tell how drunk he was by the color of his teeth: pink, just started; dark purple, stiff.”

“It’s baloney, beyond belief,” agrees John Tamm, a former FBI agent on the Philadelphia field office’s labor squad who investigated Sheeran and once arrested him. “Frank Sheeran was a full-time criminal, but I don’t know of anybody he personally ever killed, no.”

Not a single person I spoke with who knew Sheeran from Philly—and I interviewed cops and criminals and prosecutors and reporters—could remember even a suspicion that he had ever killed anyone.

Certainly, his first noteworthy mischief held no promise of underworld greatness. In 1964, at the somewhat advanced age of 43, Sheeran was charged with beating a non-union truck driver with a lug wrench—about what you’d expect from a Teamster goon. Sheeran was later twice indicted in the murders of union rivals. But in neither case did the government or anyone else accuse him of touching a trigger, only of hiring the hit men who did his dirty work for him. When Sheeran was finally convicted of something, it was for cheating his own union members. Not exactly the kind of crime that gets you invited to Don Corleone’s daughter’s wedding.

But none of Sheeran’s nonlethal past mattered or even came up once the book came out. Though Publishers Weekly called it “long on sensational claims and short on credibility,” the credulous world welcomed a solution to the mystery of Jimmy Hoffa’s whereabouts and a chance to read tales of other famous mobster mayhem. Even the New York Times’ reviewer wrote, “It promises to clear up the mystery of Hoffa’s demise, and appears to do so.” The book appeared on the Times’ extended bestseller list and has sold over 185,000 copies, according to its publisher. Charles Brandt, the former chief deputy attorney general of the state of Delaware, was, at 62, the author of a hot property.

Read full post on Slate

![Permanent Record by [Snowden, Edward]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51p%2BvSl%2B4qL.jpg)