First, a tip of the hat to Edukindle creator Will DeLamater and Kindle Formatting author Joshua Tallent for creating the Kindlepedia tool discussed here and for Kindle Chronicles podcaster Len Edgerly for bringing it to my attention by featuring it on his program recently, and to old friend, author, teacher, fellow traveler and classmate of Len’s and mine Ned Stuckey-French for getting my thoughts percolating about the pedagogical possibilities here.

I can’t imagine that there is a single Kindle owner anywhere in the world who is not already familiar with Wikipedia, the online crowd-sourced encyclopedia with over 13 million collaboratively written articles, about 2.9 million of them in English. In addition to the fact that it is the 7th most popular website in the world according to Alexa, Wikipedia is a very high-profile part of the Kindle experience already, since it is featured as a prominent channel for any user-initiated Kindle search along with Google, the Kindle Store, the Kindle’s onboard dictionary and its library of ebooks and other documents:

The opportunity for readers to move quickly and easily — using the Kindle’s absolutely free wireless 3G web browser — between content on their Kindles and the kindof supplemental references and information that they will find on Wikipedia is bound to enrich the educational usefulness of the Kindle, and not just for college students. My 11-year-old son moves seamlessly between his life and Wikipedia explanations of the few remaining things he does not understand, and I am learning more slowly to do the same. By leaving the door constantly cracked between any content that we are reading and Wikipedia’s rich universe of information and content, the Kindle offers astonishing potential for us to place the words that we read in the kinds of rich historical and cultural contexts that makes them more vivid than they could ever be in a traditional book, no matter how much we may love print on paper.

The opportunity for readers to move quickly and easily — using the Kindle’s absolutely free wireless 3G web browser — between content on their Kindles and the kindof supplemental references and information that they will find on Wikipedia is bound to enrich the educational usefulness of the Kindle, and not just for college students. My 11-year-old son moves seamlessly between his life and Wikipedia explanations of the few remaining things he does not understand, and I am learning more slowly to do the same. By leaving the door constantly cracked between any content that we are reading and Wikipedia’s rich universe of information and content, the Kindle offers astonishing potential for us to place the words that we read in the kinds of rich historical and cultural contexts that makes them more vivid than they could ever be in a traditional book, no matter how much we may love print on paper.

But Wikipedia is more than just a place to visit for a few seconds here and there in the margins of one’s reading experiences. The rich and extensive content to be found there is worthy of reading time all its own, and offers inquisitive readers an opportunity to move organically — or whimsically, for that matter — across dozens or hundreds or thousands of “articles” in ways that allow the construction of remarkable aedifices of personal knowledge and contextual understanding. Thomas Wolfe may have arrived at Harvard in 1920 with the dream of reading every volume in the university’s Harry Elkins Widener Library, but I cannot help but think that he might have enjoyed his self-education more, begun it earlier, and avoided the constant need to wash the dust from his hands if his times had allowed him access to a Kindle with an always-on Wikipedia connection.

Now, Edukindle creator Will DeLamater and Kindle Formatting author Joshua Tallent have collaborated on an extremely useful and elegant new application, called Kindlepedia, that allows Kindle readers to create a Kindle “book” within a few seconds from any Wikipedia listing and  transfer (download) it to a Kindle either via USB or Whispernet for offline reading and research at one’s leisure. Not surprisingly, given Joshua’s virtuosity with Kindle formatting issues, the resulting Wikipedia-based “book” arrives on a Kindle in an elegantly formatted, easy-to-read state, with external web links intact so that a reader is never more than a click away from extending one’s research even further, including references beyond Wikipedia. Here are the steps, and just for fun I’ll use the Wikipedia article on one of my favorite underappreciated baseball players, Bernie Carbo:

transfer (download) it to a Kindle either via USB or Whispernet for offline reading and research at one’s leisure. Not surprisingly, given Joshua’s virtuosity with Kindle formatting issues, the resulting Wikipedia-based “book” arrives on a Kindle in an elegantly formatted, easy-to-read state, with external web links intact so that a reader is never more than a click away from extending one’s research even further, including references beyond Wikipedia. Here are the steps, and just for fun I’ll use the Wikipedia article on one of my favorite underappreciated baseball players, Bernie Carbo:

- On your computer, go to the Kindlepedia page on the Edukindle website at http://www.edukindle.com/downloads/kindlepedia/. (No need to try to do this Kindlepedia procedure directly from your Kindle; I have already tried and it does not work).

- Type in the URL of the Wikipedia entry from which you wish to make a Kindle “book” in the entry field in the center of the screen or, if you are relatively certain that a brief keyword or phrase will produce the desired article, you can try that:

Click on the “Create Kindle Book” button, and within a few seconds you will see a new screen with these buttons in the center of the display:

Click on the “Create Kindle Book” button, and within a few seconds you will see a new screen with these buttons in the center of the display:

Click on the “download” button and note from your computer’s dialogue box (or a quick file search, for, in this case “Bernie_Carbo.mobi”) the location to which the downloaded file is being be served on your computer.

Click on the “download” button and note from your computer’s dialogue box (or a quick file search, for, in this case “Bernie_Carbo.mobi”) the location to which the downloaded file is being be served on your computer.- Transfer this “Bernie_Carbo.mobi” file to your Kindle either by sending it as an attachment to your @kindle.com email address (in which case Amazon will charge you 15 cents per megabyte rounded up and send the converted file to your Kindle via Whispernet) or, for free, by connecting your Kindle to your computer via USB, copying the saved file from your computer to the “documents” folder in your Kindle’s main directory via Finder, My Computer, or whatever file management program you use with your computer, and using the “Eject” Kindle command to disconnect the Kindle from your computer.

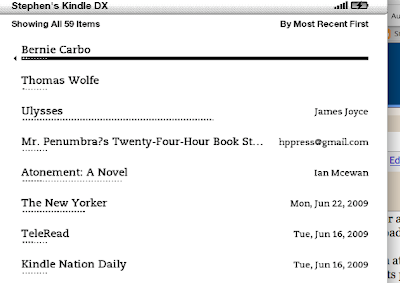

- You should now find the Kindle-formatted “Bernie Carbo” book at the top of your Kindle’s Home screen if your Home display is organized to show all documents, most recent first:

As with any other Kindle book, click on “Bernie Carbo” and begin reading or let your Kindle read the content aloud to you. While reading, you’ll be able to click on any live web link such as the Baseball-Reference link shown here

As with any other Kindle book, click on “Bernie Carbo” and begin reading or let your Kindle read the content aloud to you. While reading, you’ll be able to click on any live web link such as the Baseball-Reference link shown here

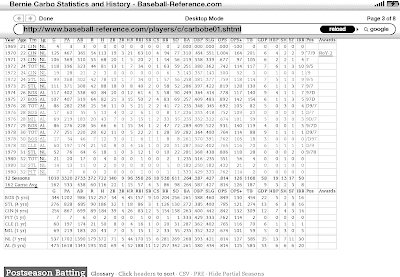

to extend your research to, say, viewing Carbo’s lifetime stats:

to extend your research to, say, viewing Carbo’s lifetime stats: Okay, if you are thinking that this great new research tool is going to curse you with an unmanageably long list or catalog of “books” on your Kindle, let’s revisit a Kindle Nation piece from March 9 (which referenced a Kindle Chronicles podcast from March 6) on A Brilliant Way To Apply Tags To Organize Your Kindle Content:

Okay, if you are thinking that this great new research tool is going to curse you with an unmanageably long list or catalog of “books” on your Kindle, let’s revisit a Kindle Nation piece from March 9 (which referenced a Kindle Chronicles podcast from March 6) on A Brilliant Way To Apply Tags To Organize Your Kindle Content:

Amazon’s failure to provide user-defined content management folders or labels is one of the major disappointments offsetting the many improvements that we have seen with the Kindle 2, but a Kindle owner named Larry Goss has developed an elegant work-around system that allows him to “tag” any title on his Kindle. To hear his approach, check out the March 6 edition of Len Edgerly’s Kindle Chronicles podcast. Larry’s idea is detailed in the show comments section a little over two-thirds of the way into the podcast. The gist of it is that you can use any Kindle’s annotation feature to “tag” your content by genre, status, or any other qualifier as long as you create “words” that would not otherwise be found in your documents. For example, I might create two tags for science fiction novels on my Kindle, and thus annotate the first page of each either with SWSCIFIREAD or SWSCIFINEW, to signify Stephen Windwalker’s science fiction novels read or unread. Once the annotation is saved, books with a particular tag will display in the search results whenever you enter that tag. Yes, it is a work-around, but I hope you will agree that it is brilliant in its elegant, workable simplicity, and join me in thanking Larry and Len.

For my purposes, I just create a tag, er, annotation, at the beginning of each of these Wikipedia-based books. The first four letters are always “swkp” for “Stephen Windwalker Kindlepedia” and subsequent letters are the briefest and most simple tag for the content, so that for the Carbo content, I simply open the file on my Kindle, choose “Add a Note or Highlight” from the Menu, type in “swkp carbo,” and click on “save note” at the bottom of the dialogue box. Then I will find the content anytime by typing in “swkp carbo,” whereas typing in “swkp” will show me all my Wikipedia-based content and typing in “carbo” will show me all Carbo references on my Kindle. Fortunately, if I forget some of my own tags, I can also access them by selecting opening the “My Clippings” file on my Home screen.