44 rave reviews!

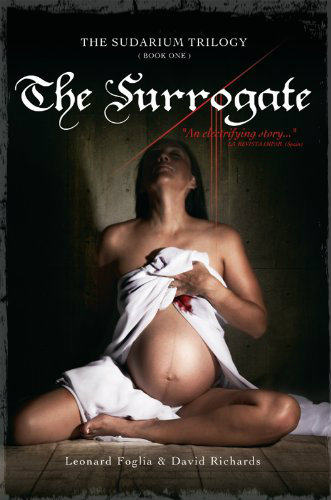

A shocking murder from the past exposes present-day secrets that rock a small town in Pennsylvania in this juicy mystery that’s fascinating readers with its parallel storylines.

A great read for only 99 cents!

1 Ragged Ridge Road

by Leonard Foglia, David Richards

The once-glorious mansion needs repair, but everything about it — the chestnut moldings, the soaring foyer, the grand staircase and twenty-two rooms — filled Carol Roblins with hope from the moment she saw it. Maybe a fresh start would improve the relationship with Blake and their learning-disabled son, Sammy, giving their crumbling marriage one last chance. But before they can resolve their tensions, Blake leaves for a military assignment in Europe.

Alone with Sammy in their new home, Carol delves into her restoration, fired by a dream of opening a bed and breakfast. As she recovers long-lost blueprints and researches the mansion’s history, she learns it was once home to a storybook couple and a shocking murder.

Praise from reviewers and readers:

“Tasty enough to tempt you into wanting…more” – The New York Times

Absolutely brilliant

:…Each chapter is either in the present or in the past and the way time slides back and forth is just way,way, way cool…Kept me turning page after page after page.”

an excerpt from

1 Ragged Ridge Road

by Leonard Foglia & David Richards

and published here with their permission

One

At first, the snow came gently—in dry, feathery flakes that slid off the gabled roof and floated down the chimneys. Those that collected on the windowsills or lodged in the corners of the windowpanes didn’t remain there long, before the wind picked them up and set them on their downward drift again. In a few hours, it would become one of those hard, icy storms that the community held accountable every winter for at least two broken legs and countless twisted ankles. For now, it settled over the slopes surrounding the mansion like gossamer silk—silent, graceful, and deceptive.

Not even the hatch marks of the chickadees marred the perfect whiteness. Their jerky movements amused her, whenever she caught sight of them hopscotching across the lawn. They reminded her of tin windup toys. But it was growing dark and they seemed to have disappeared under the bushes or beneath the front porch. She couldn’t tell. Although the chandeliers in the house cast oblong sheets of light onto the yard, what was bright and cheerful indoors turned grayish and opaque when mixed with the snow.

She sighed contentedly. Christmas was her favorite holiday, and not just for the gifts, which all her life had been extravagant and were likely to be so again this year, judging from the mounds of packages at the base of the Christmas tree. She welcomed the peacefulness of snowy nights that sealed up the mansion in a cocoon and the good spirits that overtook tile butler, cantankerous as he was the rest of the year.

Her husband had spotted the perfectly shaped tree on the northwest corner of the property. It had taken three workmen to chop it down, drag it out of the woods, and maneuver it through the front door without scratching the chestnut woodwork. Nearly ten feet tall, it sat in the large, open stairwell and filled the whole house with a fresh forest scent. The maid and the kitchen help had spent several days hanging the delicate crystal ornaments and draping the garlands of cranberries and popped corn, so that on swag drooped lower than the next and no ornament detracted from its neighbor. Later this evening, they would light the tapers that stood like sentinels at the tip of each branch.

How unfortunate it all had to come down by twelfth night, she thought as she climbed the wide staircase that wound around the tree and led to her bedroom on the second floor, then corkscrewed up another flight to the servants’ quarters and the attic under the gables. If she had her way, the Christmas decorations would never be packed away. From the parlor, she heard the strains of “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen.” Someone was at the player piano, pumping the pedals vigorously. The notes came in loud, blustery gusts. A ragtag choir of carolers from town would be making the rounds before long. From past experience, she knew that a few of them, emboldened by the gin in their back-pocket flasks, would be more than a match for the huffings and puffings of the mechanical piano.

Her fingers went instinctively to her neck. Tonight she would wear the necklace. Her guests would ooh and aah—the women envious of so many fine diamonds and sapphires, the men drawn to the pale décolletage that showed them off so well. She relished the attention in advance, knowing that as soon as the holidays were over, the jewelry would go back into her husband’s vault at the bank.

Once she reached the second floor, she glided down the long hall, entered her bedroom, and shut the heavy door. A freshly stoked fire in the fireplace threw reddish yellow shadows over the room and made the brass fender and fireplace tools shine like antique gold. Two small lamps, reflected in the mirror behind them, formed circular pools of light on the dressing table. The thick velvet curtains had been drawn against the chill by the maid, who was waiting in the kitchen for the bell that would summon her back upstairs to dress her mistress for the evening’s festivities.

The woman sat down before the mirror, removed the necklace from its case, and held it up to her cheek. Glints of silver and blue danced across the ceiling. She studied her image in the mirror, allowing a smile to break across her face. How could she not be happy? All the dreams she secretly harbored for the new year were about to come true. Voices from the living room, accompanying the music, washed up against the bedroom door: “Oh, tidings of comfort and joy, comfort and joy . . .” She hummed along with them.

A burst of wind rustling the curtains cut her reveries short. She turned to look and noticed a thin dusting of snow on the floor. The window must have blown open while she was daydreaming. She parted the curtains and checked. No, the latch was shut tight. Then something moved in the pane, a dark reflection that caused her to whirl around.

On the far side of the bedroom stood a figure in a heavy blue topcoat. A knit cap was pulled down over the eyebrows, and a checkered scarf was wound tightly around the lower half of the face. All she could make out were the eyes, which were red and watery. The gloved hands gripped the brass poker from the fireplace set.

‘Who are you? What are you doing here?” she asked indignantly.

The figure was silent.

“Didn’t you hear me? Who are you?”

The only response was a long, protracted moan. Louder, it would have been a growl.

“Get out of here immediately or I will have my husband throw you out.” Even as she spoke, she sensed the idleness of her threat. If her husband had returned home from the bank, she hadn’t heard him. With that infernal player piano making such a racket, who could hear anything? She backed up and reached for the button to call the maid. In an instant, the figure was upon her, the poker raised high like a hatchet. But it wasn’t the weapon, flashing in the firelight, that made her body go weak and dried out her mouth. It was the look of pure malevolence in the eyes,

“Oh, my God, please don’t—”

The poker came down with a furious thwack, carving a deep gash in her forehead. The next blow sent her sprawling at the foot of the bed. Short gasps of pain escaped her lips, them little bubbles of purple blood. The person was bellowing at her now, ‘Whore, filthy whore . . . you’ve got everything . . . I’m not going to let you . . .” The words entered her consciousness like broken fragments of sounds, shards cutting the inside of her head. They had no more meaning to her than the gruntings of animals.

What was happening? Where was her husband? Why this savage fury?

She curled herself into a ball as the merciless beating continued. After a moment, she saw black. Then felt nothing.

In the parlor, the player piano fell silent.

The only sound the woman might have heard, had she been alive to hear it, was the flap-flap-flap of the music roll, turning on itself.

Two

Carol Roblins loved the mansion at first sight when she and Blake drove by it that late-October afternoon. They were living in three cramped rooms on the army base at the time, the latest in a long line of temporary quarters that stretched from Georgia to southern California and now to rural Pennsylvania. Sundays, they took to exploring the towns in the area in the hope of finding a home more to their liking. At the very least, a bigger one. And this was surely the biggest one in Fayette.

The Kennedy mansion, it was still called, although the original owner, a local banker, according to the real estate agent, had died in the 1920s and his descendants no longer resided in the state. Three stories tall, it sat on a sturdy foundation of Pennsylvania fieldstone. The stucco walls were of a color and texture that reminded Carol of yellow cake. A wide veranda wrapped around the front and one side, terminating in a screened-in gazebo that was strategically situated to catch the breeze.

Summers, the windows had been hooded by green canvas awnings, but all that remained were the corroded metal awning frames, and then only some of the windows could lay claim to that bit of architectural coquetry. The canvas had long since rotted and blown away. On the sharply pitched roof, the fieldstone made a reappearance in the form of two stolid chimneys capped with little tin roofs of their own.

In all the mansion was grand from a distance, shabby up close. During the Depression, it had stood empty, a monument to the kinds of quick, flashy fortunes that had been prevalent a decade earlier. Then, after World War II, it had been turned into an apartment house, and the real decline had begun. The spacious rooms had been carved up, doors had been walled over, and fireplaces bricked up. Closets were made into kitchenettes, introducing smoke and cooking grease into parts of the house that had smelled only of cedar and rose-petal sachets before.

Still, Carol knew a potential beauty when she saw it. Although the years of neglect had taken their toll, the damage was not irreversible. The grand staircase was missing some spindles from the banister, and the treads and risers were badly scuffed. But the wood was fine-grained chestnut, something you just didn’t see these days, and could easily be brought back to its original luster. The folding mahogany doors that used to divide the living room and the dining room had been stored in the basement. Poking around in the gloom, she and Blake even came upon a couple of chandeliers, entwined in a corner like bejeweled spiders, that must have hung in the main rooms.

When they returned to the foyer, Carol immediately went to the staircase again and ran her hand lovingly along the banister. Just the feel of the aged wood was enough to set her dreaming. This glorious place could actually be theirs. Far from being put off by its tumbledown condition, she found herself thinking that it would give her something to do, besides taking care of Sammy. Not that she wasn’t devoted to her son. Sammy came first and always would. But the notion of having a house to take care of, too—this house—lodged in her head and wouldn’t leave.

Part of her acknowledged how old-fashioned she was being. Well, theirs was an old-fashioned marriage, wasn’t it? Blake went to work; she stayed home. He was the man of the family; she, the woman. They operated on a clear, if antiquated, division of the sexes and an even clearer delineation of duties.

Her head tilted back, she turned around slowly and gazed up into the open stairwell, marveling at what seemed to be a stained-glass, octagonal skylight. Decades of filth had dulled the colors, and a thick layer of dead leaves blocked out any sunlight. But her guess was right: three flights up, the original skylight was still intact. Flowers and ribbons made for an elegant pattern. Or maybe the ribbons were letters. From the distance, Carol couldn’t tell.

Blake could see the excitement in her eyes and felt an unexpected surge of tenderness for her. Her emotions had always been so transparent, unlike his. He’d loved that about her once. Perhaps he still did, deep down. Then, the tenderness abated.

The hard truth was that, more and more, he felt as if they were going through the motions of married life, making empty gestures and small talk and gliding over what really mattered. He wondered if all married couples had that sensation after a while. If they did, the guys on the base never talked about it. Blake certainly wasn’t one to bring up the subject. He’d buried himself in his job, instead. At least that was paying off. The rumors of his advancement had been growing louder lately.

“What do you think, Blake?” Carol said, determined to keep her tone neutral. Her excitement was palpable anyway.

“Is this really the answer?” he asked himself. He looked at his wife, then diverted his gaze. She hadn’t changed much in the fifteen years they’d been married. There were a few lines on her forehead, some wrinkles around the eyes, but nothing that makeup didn’t easily cover, when she bothered with makeup, which wasn’t often. She was still as slender as she was the day they had first started going out. Her blond hair had darkened since then, enough so that Carol periodically felt compelled to “help it out a little,” but she hadn’t attended to that recently, either.

All told, she was a much prettier woman than she allowed herself to be. He couldn’t remember the last time she’d really dressed up and shown off her figure. He speculated that it must have been the spring party at the officers’ club, but he had no image of her to go with his memories of that event. It seemed to him that she was more intent these days on being Sammy’s mother than his wife.

Suddenly, he was aware of the silence and realized she was waiting for an answer. “It’s awfully big,” he replied. “I’m sure we can find some place smaller. More manageable.”

“But no place is going to be this special. We deserve something special.”

He wanted to say, “No kidding,” but suppressed the urge. “You need money for special, Carol. A lot of money. Do you have the slightest idea how involved a renovation would be? And you know how much they’ve got me working now. When am I going to find the time to redo a house?”

“I’ll do it. This could be my project. Please?”

“And Sammy?”

“What about him? He’s not a baby, Blake. He could help. It would be good for him.”

She was pushing and it made him nervous. He raked his fingers through his hair a couple of times, as he always did when he needed to calm himself. It was thick and black, with a sheen that was actually the beginnings of gray. He was wearing a plaid shirt and a tan golf jacket, but even when he was in civvies, the brush cut was a dead giveaway that he belonged to the military.

Carol recognized the nervous gesture and it occurred to her that she had never seen him with his hair grown out. It had always been short. Even in his childhood pictures. If there was any wave to it, she would be the last to know.

“The whole idea is crazy,” he said, less assertively than before. He was weakening. Carol took him by the arm and walked him back into the living room. “Just look at those beautiful bay windows. They’re just like the ones we had on Thatcher Avenue. Think how much fun we had fixing up that place.”

“Thatcher Avenue was a one-bedroom apartment. This is a twenty-two-room house.”

“So, it will take us a little longer, that’s all.”

“Like the rest of our lives.”

She wasn’t going to back down. Of course, it would take time, but she could picture them rehabilitating the old mansion, working side by side, cementing their marriage along with the driveway. Sammy would have the woods and the fields to explore, and the stream that cut through them, its waters as pure and chilly as icicles.

“You always said Sammy needed a yard to play in.”

“A yard. Not his own forest. I can just see him wandering off and getting lost.”

“Blake, be serious. I really want this.”

Two days later, he gave in. It was the ridiculously low price that clinched it. Apparently, their potential beauty was, in the view of most, if not all, of the prospective buyers, a white elephant. When word got around the town of Fayette that the Roblinses had signed on the dotted line, there was general amazement and some outright laughter, while Mr. Beldman, the pharmacist, noted dryly that he didn’t want to be present when they got their first heating bill.

Blake blew his stack when it came. But then, he blew his stack about so many things that winter that Carol wondered if he wasn’t having his midlife crisis ten years early. His feelings for the mansion had never matched hers, and he seemed to resent it that he had allowed himself to be swayed by her arguments. It soon became apparent to her that the renovation wasn’t going to be the wonderful collaborative venture she had envisioned. He was not merely used to order. He thrived on it. It was what had attracted him to the military in the first place, why he had risen through the ranks to captain with such ease. And the mansion was in a perpetual state of disorder.

They appropriated the old library on the ground floor for their bedroom. A cozy office, which opened off the library, made the perfect bedroom for Sammy. Hard as they tried, however, they couldn’t keep the clutter and the dust, generated by the renovation, out of either room. There was unwanted symbolism in that, if either had chosen to recognize it. Blake grew testy and Carol’s optimism started sounding forced, probably because it was. Somebody had to keep up the family’s spirits, though.

Even she had a brief sinking feeling when part of the entryway wall crumbled on her. She was patching a large crack when the old plaster fell away in large, dry chunks. Before she knew it, she was staring at a sizable hole. Her attempts to contain the damage only made it worse. By the time Blake arrived home, she was up to her ankles in debris, and a cloud of chalky dust hung in the air.

Blake stood in the front doorway, refusing to enter. He had put on his formal dress uniform for some official ceremony that day and the polish on his black shoes gleamed like wet tar.

“What the devil is going on here?” he barked.

Carol tried to inject a little lightness into the situation. “What does it look like? I’m tearing down a wall. Bob Vila has nothing on me now.”

“Except common sense.”

“It’s just plaster, Blake.”

Angrily, he kicked a slab of plaster with the toe of his shoe. “Biggest mistake I ever made,” he muttered. “I never should have bought this place.”

‘We, Blake. We bought this place. Remember?” It infuriated her when he talked like that. As if she didn’t exist. He turned abruptly and started down the front steps.

“Where are you going?”

“I’m going around to the back door because I’m not about to track through that mess. Unless, of course, you want to get this uniform cleaned and pressed again. If we have any money left over, after pouring it all into this dump, that is.”

Carol chased after him, the conciliatory expression on her face at odds with the smears of plaster war paint on her cheeks. “You’re exaggerating, Blake. This place is going to be absolutely beautiful when we’re done. You’ll see.”

“Get real, Carol.” He stomped off toward the back of the house.

Carol took a few deep breaths, then mumbled to herself, “Loosen up, Blake.”

“Get real” had always been his response to her flights of enthusiasm, even when they were young. “Loosen up” was her usual retort. Although both commands were uttered in fun, they served nonetheless to define the fundamental difference in their temperaments. Blake was solid, reliable, a human bulwark. (His square shoulders were one of the first things she had noticed about him.) She was so much more impulsive.

For a long time, she believed their personalities to be mutually enhancing. Her imagination, her curiosity, her sense of adventure, made life more interesting for him, just as his dependability, his pragmatism (although she didn’t like the word itself), made life saner and safer for her. It was a perfect fit. Of course, relationships were more complicated than that, but as capsule analyses went, that one struck her as accurate enough. Until they began to change.

Marriage and motherhood grounded her, and while her romantic side never withered away, she learned to give it less expression, knowing how easily it was mocked and eventually telling herself that it belonged to another, simpler period in her life, like the portable pink-and-white vinyl record player she’d prized in high school. Little by little, Blake’s dependability hardened into a kind of inflexibility. Rigor, even. “Get real” lost its playfulness. So did “loosen up.” What had started out as good-natured gibes evolved into veiled criticisms. The perfect fit wasn’t so perfect, after all.

Mid-February, the promotion Blake had long been angling for came through. Carol knew how much it meant to him. He would be assistant army attaché at the American embassy in Bonn, a posting that was bound to expand his contacts. If he performed well—and here Blake took care to quote his commanding officer exactly—he could expect “a career-enhancing billet at the Pentagon in the not very distant future.” Carol tried to get excited for him, but the thought of packing up again and leaving a spot that had fired up her dormant imagination dampened her enthusiasm.

“What about the house?” she asked, trying not to sound too disappointed.

“What about it?”

“I don’t want to sell it and move again.”

“We won’t have to.”

“How can we afford to keep it? Who’ll rent it in this state? One peek at this kitchen . . .” She let the sentence trail off with a vague gesture at the surroundings. The old fashioned kitchen appliances and the chipped linoleum floor put it better than she could.

“I . . . uh . . . I . . . thought . . . uh . . .” He stopped. As a child, he had stammered badly, but he had gotten over the habit in high school when he learned not to rush his thoughts. One of the few occasions Carol had heard him succumb to the stammer was at his mother’s wake, and it had been painful to hear. She hoped he was just fumbling for the right words this time.

He sounded them slowly. “I . . . uh . . . well . . . I thought that I would go alone.”

Instantly, Carol realized what was happening. The long, festering discontent was about to surface. In fact, it just had. It was out. Spoken. There could be no pretending otherwise. “Oh” was all she could manage.

“It’s only a temporary position.” he rationalized. “A year at most. You know how fast things can change over there. Why uproot Sammy one more time? The year will be over before any of us knows it.”

He rocked awkwardly on his feet and cleared his throat before adding, “We need the time apart, Carol. To figure out where we stand with each other.”

She couldn’t bring herself to face him. “Where do we stand, Blake?”

“I don’t know.”

“And so you’re going to run away to the other side of the world. Is that it?”

“I’m not running away. This is work. My career. It’s important to me.”

“More important than your family?”

“Look at me. Are you happy?”

The question caught her unaware and her heart contracted. She was incapable of giving him an easy answer. Sure, she was occasionally disappointed in their lives together, as was he. But did that qualify as unhappiness? Or was it a sign of carelessness, of inattention, on one another’s part? And when had disappointment become grounds for a separation, anyway?

As she sank to a kitchen chair, her tears began to flow, slowly at first. But the more she tried to bring them under control, the faster they came, and before long she was sobbing audibly. Blake paced back and forth, confining his steps to the worn patch of linoleum in front of the sink. Displays of emotion made him acutely uncomfortable. Pacing was how he coped.

“I’m sorry. I can’t help it,” she apologized, but that only made her sob all the more.

He came up behind her and placed his hand on her shoulder. She reached up and clutched it, and they stayed that way for several minutes, not saying anything, until Carol’s crying subsided. Then she released her grasp, went to the sink, and splashed some cold water on her face.

“I must be a sight.” Why was she always the one to cry, never Blake?

He held out his handkerchief, but she rejected it with a shake of the head.

“Have you given any consideration to Sammy?” she asked, the faintest trace of accusation creeping into the question.

“He spends so much time with you, he probably won’t even notice I’m gone.”

“How can you say that? The boy worships you.”

“That so? You could have fooled me.”

“He just doesn’t express himself like other kids. You know that. You keep expecting him to wake up one morning and have this animated conversation at breakfast with you about the Yankees. That’s never going to happen. You’ve got to stop waiting for him to come to you and take the trouble to enter his world. That is, if you want a relationship with your son.”

They’d been over this ground so often in the past she could hear Blake’s response before he uttered it.

“You coddle him too much.”

“Please, let’s not have that discussion again. What are we going to tell him? Or rather, what are you going to tell him? Because I’m not handling this one. Sammy’s going to have to hear this from you,”

They talked late into the night—sorting out their relationship and how it had come to this impasse. Once they got beyond the anger and the accusations, they actually addressed some problems that should have been tackled long ago. Simple things such as how Carol felt about moving every couple of years. (She had never liked it.) Or why Blake was so reluctant to express his emotions. (He considered it a weakness.) Little was resolved, but the rift no longer struck Carol as this fearsome chasm, ready to swallow them up. She could see its shape and its depths—and its perils—more clearly, and that consoled her. Sad as it was to think how long they had been drifting apart, somewhere in the back of her consciousness was a spark of relief that the truth had finally been acknowledged.

By the early-morning hours, they were talked out and exhausted. Resigned to Blake’s leaving, Carol had convinced herself it was just another army assignment, not a trial separation. Blake was no longer feeling such hangdog guilt. They even allowed themselves to look back on better days. Carol laughed out loud when Blake recalled the first time she had prepared her special apple-cinnamon soufflé. They had been married only a few weeks and she had slipped out of bed at sunrise, hoping to surprise him with her culinary skills. She had put the two soufflés in the oven and then tiptoed back into the bedroom. Blake had reached out for her and they had started to kiss. The kissing got out of control and one thing led to another. Not until their desire was appeased and they lay spent and contented on the bed did they smell smoke coming from the kitchen.

The soufflés were ruined. Carol was distraught, even though Blake assured her that their time in bed was better than any soufflé could ever be. He was finally able to calm her down only by picking the few edible pieces out of the charred pan and proclaiming them delicious. The episode had given birth to a long-running joke: “Do you want sex or a soufflé this morning? Because you can’t have both.”

Sex usually won out in those early years.

The day Blake left for Germany, it snowed, and then the snow turned to slush. Carol had decided to make the departure into a going-away party, mostly for Sammy’s sake, and she’d gone to the trouble of preparing three of the famous soufflés. But the festive mood soured when Sammy stayed in his room and refused to come out for breakfast.

Blake went in to fetch him. Seated by the window, Sammy was absorbed in the task of polishing a small silver object. It was typical of his son, thought Blake, to be lost in his own world. But did it have to be today of all days? He tried to stifle his annoyance.

“Hey, buddy. Don’t you want some breakfast?”

“No.”

“Aren’t you hungry?”

“No.”

“Mom made our favorite soufflés.” Sammy said nothing and continued diligently to rub the silver object. Blake saw that it was a spoon. “Where did you get that. Son?”

“Found it.”

“Where?”

“Outside.”

“Do you like it here, Sammy?”

“Yes.”

“Well, so does your mom. That’s why I’m going abroad alone. So you guys don’t have to move again. I’ll get my work done as soon as possible and then I’ll come back. That way, we can keep the house. Do you understand that?”

Sammy raised his head. The expression on his face was blank. Blake wondered if his son believed him.

“Besides. I couldn’t take you, even if I wanted to.”

“Why?”

Blake leaned down and whispered conspiratorially in Sammy’s ear, ”I’m going on a secret mission.”

Sammy perked up. “What’s the secret?”

“Well, it wouldn’t be a secret if I told you now, would it? But you know what we’re going to do?”

“What?”

“We’ll have a special code, you and I.”

“What’s that?”

“That’s something that no one else understands. Just us. I’ll call you every week, and if I say, ‘The weather was good this week,’ you’ll know I’m okay and the mission is going well.”

“That’s silly.” Sammy giggled.

“Well, what should the code words be, then?”

Sammy mulled over the question seriously. Then he held up the object in his lap. “Shiny spoon.”

“Shiny spoon?”

“Yes. If you’re all right, say ‘shiny spoon.’ ”

“Okay, it’s a deal.”

“And if you’re not all right . . .” Sammy thought long and hard before chirping brightly, “Say ‘shiny knife.’ “

After breakfast, Carol hugged Blake on the veranda and babbled something ridiculous like “Take care of yourself.” Sammy ran down the steps and waved until the car that had come to pick Blake up had rounded the bend in the road and disappeared from sight. As she turned to go back inside, Carol looked up at the house. It was a big, old mess, she thought, but it was her big, old mess. In the few months they had lived there, she had a stronger feeling of belonging than she had experienced anyplace else. Even if things were never repaired with Blake, in some strange way she couldn’t articulate, she felt that she’d come home at last.

Three

The sergeant had seen his share of dead people—those claimed by accidents or disease or old age—but he’d had few dealings with murder victims in his carrier. A vagabond knifed in a drunken brawl, a farmer who had drowned his wife—that was about it. They had been tawdry killings and attracted little attention.

The woman who lay at the foot of the canopied bed belonged to another class. She had elegance, wealth, breeding. The bedroom alone attested to that. He recalled tipping his hat to her when they had passed on main Street and had trouble reconciling that image with the body that lay on the floor. She looked like a smashed china doll—fragments of her beauty floating in a pool of crimson blood. He felt the nausea rising in his throat, swallowed hard, and turned away.

He could see that the murderer had escaped by a side window, which was still open and gave on to the roof of the veranda. One of the red velvet curtains had been partially torn form its rod, and snow was blowing into the room. Faint footprints were discernible on the roof, but the storm was filling them in fast. The sergeant knew they would be completely covered over before they could provide any significant clues.

“It’s gone.” The maid, visibly shaken, hovered in the doorway. “I don’t see it. It’s gone,” she repeated shrilly. The sergeant had immediately put the bedroom off-limits to the staff of the mansion, but in the maid’s case, it was an unnecessary precaution. Her eyes were round with terror and she had no intention of venturing any closer to the dead body.

“What’s gone?” The sergeant cast his eyes about the room, not certain what she was referring to.

“The necklace. The necklace she was going to wear tonight. There’s the box.” The maid pointed to an empty velvet jewelry box on the dressing table. “Someone’s taken it.” She crossed herself several times and began chanting “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death,” Over and over. The litany sounded like whimpering to the sergeant and aggravated his nerves.

“Where is Mr. Kennedy?” he snapped. “Does he know what’s happened yet?”

He turned back to the maid, not really expecting an answer. She had buried her head in the neck of the butler, who was attempting to comfort her and remain stoic, although the grisly sight of his mistress’s battered body upset him no less deeply. Suddenly, a flurry of activity could be heard below. The forensic specialist—or the mousy gentlemen who fulfilled that function on the small police force—a photographer, and half a dozen other officers had arrived on the scene.

“He was here,” the butler spoke up. ‘Then he left.”

“Left?”

“Yes.”

“Where the hell did he go?”

“I don’t know,” the butler replied, sounding more stupid than he would have liked.

A jolt of energy coursed through the sergeant. He bolted out of the bedroom and started for the grand staircase. ‘What kind of a car was he driving?” he called back to the butler and maid, who were following after him.

“No car. He was on foot,” the butler said.

“He didn’t even bother to take his overcoat,” added the maid, who had regained some of her composure. “He just left. We couldn’t stop him.”

“Which way did he go?” barked the sergeant as he reached the foyer. The butler gestured toward the front door. The sergeant promptly ordered two young officers into the night to see if they could spot any traces of the man’s flight. With the snow coming down harder and harder, it seemed unlikely. He cursed to himself. The irritating “Holy Mary, Mother of God” had resumed. He cursed again. The investigation was not off to a promising start.

Within the hour, the mansion was swarming with policemen and detectives who had been Summoned from Harrisburg. The upper floors of the mansion were cordonned off, and the help, less terrified now than dazed, collected in the kitchen. The cook had brewed a large pot of coffee, but nobody was drinking it.

Some officers, at a loss at what to do, milled about the living and dining rooms, trying to look purposeful but mostly taking in the furnishings. There had been a lot of talk in the town when the mansion had gone up. Now they were getting a chance to see for themselves how bankers lived.

In the dining room, on a long table covered with antique lace, heavy silver and crystal glasses caught the light from the chandelier and sparkled. Chafing dishes on the cherry sideboard suggested the generous amounts of food that would be served later in the evening. Or would have been. Boughs of pine trees adorned the mantelpieces, adding to the fragrance of the stately Christmas tree in the foyer. It was festive, opulent, lifeless.

A spanking new 1928 Ford, driven by a well-dressed man, chugged into the driveway. Next to him sat a woman in a sable coat. Packages were piled up on the backseat.

“Oh, my god, the guests,” the maid wailed. ‘What are we going to do?”

“How many are you expecting?”

“About fifty.”

The sergeant singled out a chubby-faced officer barely in his twenties, standing in the foyer, one of the few men who had chosen not to go upstairs and view the corpse. “Billy,” he ordered. “Don’t let anyone up here. Block off the end of the road.”

‘What do I tell them?”

The sergeant felt a great weariness come over his body. A murder like this was terrible enough, but that it should happen now, during the season of peace and goodwill, made it doubly awful to him. ‘Tell them,” he said with a wry nod of the head, “that Christmas has been canceled this year.”

Outside, there was a stomping of boots on the veranda, then the front door opened. A frostbitten policeman stumbled in, out of breath, shaking snow from his cap. “We found him.”

The house went silent.

“You found who?” the sergeant asked.

“Charles Kennedy. The husband. We found him.”

… Continued…

Download the entire book now to continue reading on Kindle!

LEONARD FOGLIA is a theater and opera director as well as librettist. His work has been seen on Broadway, across the country, as well as internationally.

He directed the original Broadway productions of MASTER CLASS, THURGOOD and THE PEOPLE IN THE PICTURE as well as the revivals of WAIT UNTIL DARK and ON GOLDEN POND.

Off Broadway he directed Anna Deavere Smith's LET ME DOWN EASY as well as the national tour and ONE TOUCH OF VENUS at Encores!

His opera credits include the premiers of three operas by Jake Heggie - MOBY DICK (Dallas Opera), THREE DECEMBERS and THE END OF THE AFFAIR (both Houston grand Opera). His production of Heggie's DEAD MAN WALKING has been seen across the country.

As a librettist his opera CRUZAR LA CARA DE LA LUNA (To Cross the Face of the Moon) with music by Pepe Martinez had it's premier at Houston Grand Opera in 2010 and was performed at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris in the fall of 2011.

LEONARD FOGLIA is a theater and opera director as well as librettist. His work has been seen on Broadway, across the country, as well as internationally.

He directed the original Broadway productions of MASTER CLASS, THURGOOD and THE PEOPLE IN THE PICTURE as well as the revivals of WAIT UNTIL DARK and ON GOLDEN POND.

Off Broadway he directed Anna Deavere Smith's LET ME DOWN EASY as well as the national tour and ONE TOUCH OF VENUS at Encores!

His opera credits include the premiers of three operas by Jake Heggie - MOBY DICK (Dallas Opera), THREE DECEMBERS and THE END OF THE AFFAIR (both Houston grand Opera). His production of Heggie's DEAD MAN WALKING has been seen across the country.

As a librettist his opera CRUZAR LA CARA DE LA LUNA (To Cross the Face of the Moon) with music by Pepe Martinez had it's premier at Houston Grand Opera in 2010 and was performed at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris in the fall of 2011.