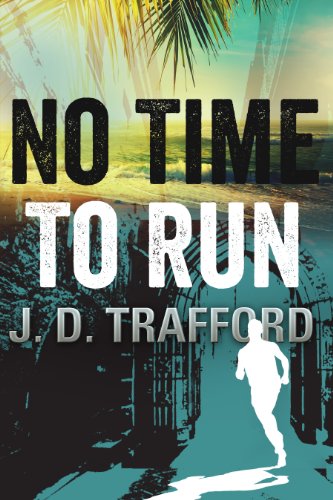

A “writer of merit” —Mystery Scene Magazine

Like John Grisham and D.W. Buffa, award-winning author J.D. Trafford created a smart legal thriller that keeps the reader turning pages.

Michael Collins burned his suits and ties in a beautiful bonfire before leaving New York and taking up residence at Hut No. 7 in a run-down Mexican resort. He dropped-out, giving up a future of billable hours and big law firm paychecks. But, there are millions of dollars missing from a client’s account and a lot of people who want Michael Collins to come back. When his girlfriend is accused of murder, he knows that there really isn’t much choice.

And here, for your reading pleasure, is our free excerpt:

CHAPTER ONE

Inches away, Kermit Guillardo’s breakfast of hard-boiled eggs, marijuana, and salsa rode heavy on his breath. “Rough night?” A small piece of egg dangled from Kermit’s nest of a beard.

“Can you give me a minute here?” Michael pushed the empty Corona bottles away from his body, closed his eyes, and laid his head back onto the sand. It was a temporary respite from the Caribbean sun and a world-class hangover.

“Tin bird leaves in just a few ticks of the clock, mi amigo.” Kermit’s head bobbled. His swaying gray dreadlocks mirrored the thoughts kicking around inside. “Next flight won’t be ‘til late, so you better rise and shine, maybe fetch yourself a clean shirt.”

Michael didn’t respond. His mouth was dry, and a dozen tiny screws were inching their way into the deeper portions of his brain.

“Andie called, again.” Kermit put his hands on his hips. “She’s freaked out, man, very freaked out. Cops like won’t talk to her, so she’s just stirring in jail wondering what’s goin’ on an’ all.”

“What’d you tell her?”

“Told her you were flying out first thing. Didn’t tell her you were passed out on the beach, though.”

“I appreciate that.” Michael sat up.

“No problemo, mi amigo.” Kermit brushed away the compliment. “I’ve found that ignorance is often the key ingredient of a well-settled mind.” He nodded, agreeing with himself, then his expression turned serious. “You really a lawyer? I know you said you were and all, but… people say a whole lot of things down here.”

“I was.” Michael touched the small scar on his cheek. “And, I guess I still am.”

Kermit nodded as his mind worked through the information. Finally, he said, “You don’t look like a lawyer.”

“Well I clean up pretty good. You’d be surprised.”

With that, Kermit smiled wide. “I bet you do.” He leaned over and offered Michael his hand. Michael took it. “You know Andie’s like a sister to me.” Kermit pulled Michael to his feet.

“I know.”

“Tendin’ bar here and taking care of this little resort is the only job I’ve ever managed to keep, not that Andie couldn’t have fired my ass like a million times by now…” Kermit’s voice drifted away with the thought, and then circled back. “She didn’t do what they say she did, man, not my Andie.”

“I know she didn’t.”

“You gonna straighten it out?”

Michael started to answer, and then stopped. He had only been a lawyer six years before the “incident” that caused his premature retirement from the practice of law, but he had been asked that question hundreds of times by clients. Usually the answer was a hedge. He knew not to commit― the cops won, even when they shouldn’t, and there were some problems that even the best lawyer in the world couldn’t fix― but, this time was different. It wasn’t a client. It was Andie, a woman who had stopped him just short of the edge. A woman he loved.

“I’m going to bring her back.” Michael looked Kermit in the eye. His voice was steady, although everything else inside churned. “Whatever it takes.”

CHAPTER TWO

He had sworn that he would never practice law again. Michael John Collins had quit his job. His Brooks Brothers’ suits and silly striped ties were burned in a glorious back-alley bonfire, and he had given away just about everything else he owned. He had dropped out, and remained dropped out, living in the beautiful mess of shacks and huts, about an hour south of Cancun, that comprised the Sunset Resort & Hostel.

Listed in The Lonely Planet guidebook under “budget accommodations,” the Sunset promised and delivered: “An eclectic clientele of backpackers, hippies, and retirees that is a little more than a half mile down the road from the big chains, but a million miles away in every other sense.”

It was just what Michael had needed. He couldn’t really say whether he had fallen in love with Andie first, and then signed the over-priced lease agreement, or vice versa. But, either way, he had been an easy mark. Hut No. 7 at the Sunset Resort & Hostel had become his home, more than any place else he had ever lived.

As Michael finished gathering his toiletries and a change of clothes, he picked up the framed picture of his namesake. Growing up, his mother had hung three photographs above the dining room table in their small Boston apartment. The first picture was of Pope John Paul II. Next to it, there was a picture of President John F. Kennedy. And, the third, and most important, was a black and white photograph of the Irish revolutionary, Michael John Collins.

Michael had been named after him, and, when he was little, he would pretend that the revolutionary leader was his real father. The photograph was taken shortly before the Easter Rebellion against the British in 1916. The revolutionary was young at the time, in his mid-twenties, but the look on his face was hard and determined with a glint of mischief.

Michael didn’t believe in politicians. And, his belief in religion came and went depending on the day, but the Irish revolutionary was a constant. He had kept the photograph after his mother had died of lung cancer during his senior year of high school. The picture gave him comfort, a thin tether to the past and loose guide for the future.

He wrapped the photograph in a few shirts and placed it into his bag, ready to do battle once again.

They were getting close, Michael thought. His two worlds, past and present, were coming together. Andie was somehow caught between. As he closed his knapsack, Michael looked around Hut No. 7 and wondered whether he would ever be back.

“You coming?” Kermit stuck his head through the open door. “We gotta shake a leg and head toward the mighty coastal metropolis of Cancun, my man. Tick-tock, tick-tock, tickity-tickity-tock.”

Michael turned toward Kermit. “I’m coming.” He threw his knapsack over his shoulder, and took a last look at his sparse living quarters before walking out the door.

“You seem a little gray, dude, like a long piece of putty brought to life by a bolt of lightning and a crazy-daisy scientist or two.” Kermit reached into his pocket and removed a small plastic bag. As they walked past the Sunset’s communal bathrooms, he held the baggie in front of Michael’s face. “Me thinks you need a little somethin’ somethin’ to sooth your troubled mind.”

Michael looked at the bag filled with a cocktail of recreational drugs, and then pushed it away. “You a dealer now?”

“No, man,” Kermit said. “Dealers sell, I, on the other hand, give.”

“That’s deep.” Michael walked past the Sunset’s cantina and main office, and then to Kermit’s rusted cherry El Camino. He placed his knapsack in the back, and began to open the passenger side door.

“Hold on there young man.” Kermit stopped Michael by grabbing hold of his shirt. “The doctor does not simply dismiss patients without providing some care.” He retrieved two light blue pills from his baggie, and stuffed them into the front pocket of Michael’s rumpled shirt. “Dos magic pills.”

Michael looked down at his pocket and wondered what the jail sentence was for possession of two valium without a prescription. Then, he got in and closed the door as Kermit walked around the front to the driver’s side.

“Senor Collins. Senor Collins.”

Michael looked and saw two young boys running toward them as the half car/half truck roared to life. Their names were Raul and Pace, the star midfielder and the star striker for the school soccer team. Michael was their coach.

“Senor Collins, wait.”

“We have to go, mi amigo.” Kermit shifted the El Camino into gear. “Time’s wasting.”

Michael raised his hand. “Hold on a minute.” He rolled down the window, and leaned outside. “Aren’t you two supposed to be in school?”

The boys stopped short of the passenger side door. “Heard you were leaving.” Raul avoided the question.

“Wanted to say good-bye,” Pace said.

“I’ll be back.” Michael tried to sound convincing.

“You are going to help Senorita Larone?”

“I hope so.” Michael reached into his back pocket and removed his wallet. “I’m not sure how long I’m going to be gone, but I need to hire you two for a very important job.”

The boys looked at each other. The smiles were gone. It was all business.

“This fellow over here,” Michael nodded toward Kermit, “is going to need a little help running this place. Do you think you two can come over here after school and do what needs to be done?”

Raul and Pace nodded without hesitation.

“But you have to go to school and study hard. If I learn that you’ve been skipping, again, then that’s it. No second chances. Agreed?”

They nodded.

“All right.” Michael handed the boys a small stack of pesos. “Be good.” Michael then turned toward Kermit and tapped the dashboard. “Let’s go.”

CHAPTER THREE

Inside the airport, Michael’s nerves had grown worse. What little confidence he had shown Kermit that morning was in retreat as he made his way through one line, down a corridor, and then through another.

Everything was lit-up by the bright artificial glow of fluorescent bulbs. The light bounced off of the polished floors and tiled walls, giving the airport a disorienting hum. Parents and kids, honeymooners, and college trust fund babies hustled from check-in to security, and then to the gate.

Michael’s low-grade headache turned up a notch. The dozen tiny screws had joined forces. They were now working as one, drilling deeper into his head.

After getting his ticket and seat assignment, Michael floated along in the stream of passengers until he found a gift shop. He bought a pre-paid calling card, and then looked for a bank of pay phones.

Michael had what could loosely be described as a plan, but thinking about it turned the screws tighter and forced his stomach into a remarkable gymnastic routine.

He eventually found a payphone. Michael hesitated at first, and then picked up the receiver.

Following the instructions on the back of the calling card, Michael took a deep breath, and then punched-in a series of numbers. He paused, and then finished dialing. A long time had passed since he had last called, and, if asked, he probably couldn’t say the specific numbers out loud, but his fingers remembered.

“Wabash, Kramer & Moore.”

The woman who answered was professional with an edge of perkiness. It was a style that was pounded into all of the receptionists at the firm: be nice, not chatty; be quick, but act like you care.

“Lowell Moore,” Michael said. The screws turned, again.

“One moment.” A new series of pauses and clicks ensued, and then finally another ring and a click.

“This is Lowell Moore’s Office.”

“Hello,” Michael said. “Is this Patty?” Patty Bernice was Lowell Moore’s longtime legal assistant. She was a short round woman who was considered by most associates in the firm to be a living saint. She took the blame for mishaps that weren’t her fault, and often placed a blank yellow post-it note on the side of her computer screen as a warning to all associates and paralegals that Lowell was in one of his “moods.”

“Who is this?”

“Michael.” He took a deep breath. “Michael John Collins.”

Another pause, longer this time. “Michael Collins,” Patty said. “It’s been a while.”

“It has, too long to be out of touch.” He lied. “Is Lowell around? I know he’s busy, but I’m calling from an airport in Mexico and it’s pretty important.”

“I think so,” Patty said. “Let me see if he’s available.”

There was a click as Michael was put on hold. He hadn’t thought about what he would do if Lowell pushed his call into voicemail. He just assumed that the conversation would happen, but, the longer he was on hold, Michael began to wonder.

Minutes passed, and then Michael heard his flight number being called over the public address system. Pre-boarding had begun.

“Come on,” Michael said under his breath. He looked at his watch, and started to fidget, then, finally, a familiar voice.

“Mister Collins.” Lowell spoke with far too much drama. “A surprise. How are you? Good to hear from you.”

“Good to talk to you too, sir.” Michael’s voice was higher now, and each word was distinct and clear. It was his bright-young-associate-voice, and it shocked Michael how fast it came back to him. “Listen, Lowell, I know you are busy so I’ll get to the point. I have a friend who’s in some trouble up there, and I was wondering if one of the investigators at the firm could check it out.”

There was silence.

Michael sensed the wheels turning in Lowell’s head. Lowell Horatio Moore was the only one of the three named partners still working at Wabash, Kramer & Moore. Tommy Wabash died of a heart attack at age forty-seven. In the end, the 5’9 son of protestant missionaries weighed in at a remarkable 287 pounds. Jonathan Kramer “retired” after a murky and rarely discussed incident involving a female summer associate, his sailboat, enough cocaine to jack-up an elephant, and inflatable water toys.

“An investigator,” Lowell said. “I don’t know.” The firm’s on-book investigators, meaning investigators that were officially on the Wabash, Kramer & Moore payroll, were billed out at $275 per hour. The off-book investigators were paid at least four times that much, depending on the information or task assigned to them. The off-book investigators were usually former FBI or cops. They weren’t afraid to conduct business in ethical gray areas and that risk was rewarded. Most of the firm’s cases were won or lost based upon what they found.

Michael knew his request would divert one of those precious billing machines from the paying clients with nothing in return, so he had to give Lowell something.

“I’m thinking about coming back.” Michael said it with such earnestness that he almost convinced himself. “I’m not sure, but I thought maybe I could get set-up in the visiting attorney’s office, do any extra work that you might have, and then handle this case for my friend, kind of a pro bono deal to get me back into the swing of things.”

Lowell was silent, again, thinking through Michael’s offer.

The turn-over at the 1,500 attorney law firm of Wabash, Kramer & Moore was incredibly high. It bled senior-level associates. Either they burned-out and became high school teachers or went someplace else with a vague hope of having a life and seeing the spouse and kids, assuming the spouse and kids hadn’t already left them.

“Sure you’re up for that?” It was Lowell’s attempt to sound concerned about Michael’s welfare, but he couldn’t disguise the excitement. His young protégé might be back.

“It’s been over two years,” Michael said. “I think it might be time.”

Lowell thought for a moment. “Are you here, now?”

“No, I’m at the airport.” Michael looked at the line of passengers winding through a series of ropes, and disappearing through the gate assigned to his flight. “My plane’s about to take-off.”

Lowell asked for Michael’s flight information, and then told Michael that he was going to send a car for him when he arrived. “You can stay in my guesthouse.”

“You don’t have to do that.”

“I wouldn’t have it any other way.” Lowell continued, everything was a negotiation. “And what was the name of that friend of yours?”

“Andie Larone,” Michael said. “She was arrested yesterday. Don’t have many details because Andie doesn’t know much herself.” Michael felt his stomach flip. “When she asked for an attorney, the cops stopped talking to her. That’s why I need the investigator.”

“We can talk more about that when you get here.”

Michael said good-bye, and just managed to get out a quick “thank you” before the chips, beer, and tequila from the previous night crept upwards.

CHAPTER FOUR

Michael’s ears popped at 28,000 feet. Noise filled his head. He was swimming in sounds— the rattling coffee cart, the coughing man in aisle 8, the snoring woman in aisle 17, and, of course, the bing-bing of the seat belt warning light turning on and off, off and on.

Michael raised his small plastic cup and rattled the remaining cubes of ice. The stewardess noticed him, gave a nod, and then worked the beverage cart back. With each step she smiled, then snapped a wad of gum, smiled, and then snapped, again.

“Another Rum and Coke.” Michael handed her the cup.

“Just enough Coke to make it brown?” she asked with a southern lilt.

“A very light tan.” Michael opened his wallet and removed a few bills.

“This one’s taken care of, sweetie.” Her smile maintained, but Michael continued to hold out the money, expecting the stewardess to take it. “It’s all paid for,” she said, again. “That gentleman in the back already gave me the money.” Smile, snap. “Said he was a friend of yours and figured you’d be a little parched.”

Michael turned, and scanned the seats behind him with a lump in his throat. “Which man?”

The stewardess looked, initially maintaining her chew of the gum and perky demeanor, but the smile faded. “Now that’s a weird ‘un,” she said; snap with no smile this time. “I don’t see him no more.” She shrugged her shoulders, handed Michael his drink, and then continued down the aisle with her cart.

The smile and snap returned after just a few steps, but for Michael everything became a little tighter. His seat became smaller. The row in front of him became closer. The ceiling dropped a foot, and the other passengers crowded in.

He got up and walked down the aisle. Michael looked for someone, although he didn’t know who. Up the aisle, and then back again. Nothing.

Michael returned to his seat. A weight pressed down on his chest.

He reached into his knapsack, and removed the red envelope from the bottom of the bag. He stared at the large block lettering on the front of the envelope. It was addressed to him: Michael John Collins, Esq.

He had received the envelope two weeks earlier. It had been a lazy day, sunny and typical. After a morning of Hemingway and an afternoon of poems by Ferlingheti, Michael wandered back to Hut No. 7 to wash up and change clothes for dinner with Andie. A new Italian restaurant had opened up on Avenida Juarez in Playa del Carmen, and, although it was hard for Michael to believe, he was actually excited to taste something made without avocados, lime, or cilantro.

Michael hadn’t seen it at first. The envelope was on his pillow, and it wasn’t until he came out of the bathroom a second time that the envelope caught his attention.

Initially he thought it was from Andie or maybe even left by Kermit as some type of joke. Then, he opened the envelope and thought otherwise.

It was the beginning of the end.

The front of the card was a picture of the New York City skyline. Inside, there was no signature or note, only the pre-printed message:

MISSING YOU IN THE BIG APPLE

HOPE TO SEE YOU SOON

Michael looked up from the card as the memory merged into the present. He put the card back inside the envelope, and then scanned the plane, again, for a familiar face. After craning his neck for long enough to make the people sitting around him nervous, Michael set the card down. He reached into his pocket and removed Kermit’s two magic blue pills.

He popped them into his mouth with a chase of Rum and Coke. His ears popped, again, and Michael’s head filled back up with sound. He closed his eyes and decided to keep them closed until the captain announced their descent into La Guardia airport.

###

When the plane touched down in New York, Michael waited for all of the people that sat behind him to exit first. He watched as each person wobbled down the aisle, hoping for a moment of recognition that never came.

Eventually, the smile-snap stewardess approached to inquire if there was something wrong. “No,” Michael said. “I’m going.” He picked up his knapsack, climbed out of his seat, and walked toward the exit.

As he stepped from the plane onto the enclosed walkway leading to the terminal, cold winter air rushed through a narrow crack. He must have shaken, because the stewardess laughed.

“Might need to think about buying a jacket,” she said.

Michael turned, couldn’t think of anything witty to say, and so he turned back, continuing up the walkway.

With each step, the muscles in Michael’s body became more tense. Nothing felt natural, and Michael had to remind himself to breathe. One foot in front of the other, he told himself, keep moving.

Michael stepped into the terminal. He half-expected to be rushed by thugs brandishing semi-automatic weapons or maybe a group of men in ski masks would throw a hood over his head and ship him off to a dark hole.

His eyes darted from one person to the next, but there were no thugs. There was, however, something worse: Agent Frank Vatch.

Agent Vatch was one of the meanest and nastiest paraplegics he had ever known, although Michael didn’t know a whole lot of paraplegics. Rumor had it that Vatch’s demeanor was caused by the origin of his disability. Some said he was paralyzed when a donkey kicked him at a petting zoo as a child, others said that he was snapped in half by his grandmother’s malfunctioning La-Z-Boy recliner, and still others believed the paralysis occurred during his first sexual encounter.

Michael had his own theory: Agent Frank Vatch was simply born an asshole.

“Michael Collins.” Vatch wheeled toward him with a crooked grin. His narrow tongue flicked to and from the edges of a slit, assumed to be his mouth. “A weird co-winky-dink running into you here after such a long absence.” He wheeled closer. “If you would have called I could’ve gotten flowers, maybe chocolates.”

“A call would suggest I liked you, Francis.” Michael knew that Agent Frank Vatch hated the name Francis.

He kept walking. He continued into the terminal’s main corridor, putting his hands in his pockets, so that Vatch wouldn’t see them shake.

“My sources tell me you are going back to the original scene of the crime.” Vatch wheeled faster to keep pace with Michael.

Michael still didn’t respond. He followed the exit signs. His eyes straight ahead, ignoring the chain restaurants, vending machines, and shoe shine stands.

“You couldn’t need the money so soon.” Vatch laughed, while Michael kept going.

Michael walked up to the customs desk, handed the official his passport, said he didn’t have anything to declare, and was waived through.

Vatch flashed his badge and followed behind.

“Or could it be that you do need the money?” Vatch whistled. “Now, that would be something, burning through all that dough in just over two years. What was the grand total, again?”

“Don’t know what you’re talking about.” Michael kept going. His head was cloudy from the valium, and he wondered if he was really having this conversation. Michael knew that he would have to deal with Vatch at some point, but not like this, not so soon.

A man in a long black coat stood in front of the door holding a white sign with Michael’s name on it, and Michael remembered Lowell’s offer to arrange for a car. “Thank you, God,” Michael mumbled under his breath. He pointed at the sign. “That’s me. Let’s go.”

The driver hesitated as he noticed the man in the wheelchair ten yards behind giving chase and saying something about secret bank accounts.

“He’s not with me,” Michael said to the driver. “Just a crack-pot.”

“Fine, sir.” The driver took Michael’s knapsack into his hand, his eyes lingered for a moment on Michael’s sandals, torn pants, and wrinkled shirt. “Gonna be cold,” the driver said, and then started walking.

Michael followed him out of the terminal to a shiny black Crowne Vic. The sun was setting, and everything was cast in an orange tint, even the inch of New York slush that had settled into the nooks and crooks of the otherwise cleared sidewalk.

The driver opened the door and Michael got in.

“See you, Francis.” Michael closed the door, and Agent Frank Vatch flashed an obscene gesture. He also shouted something that likely went along with that gesture, but Michael couldn’t hear what was said.

The driver put the key in the ignition, and started the car. He began to shift the car into gear, but stopped.

“You an internet guy?”

Michael thought about it, and then nodded. “Yeah.” He saw no sense in disturbing the only rational explanation the driver could think of for helping a thirty-something hippie escape in a limousine from an angry paraplegic.

“Lost my f’n shirt in the bubble,” the driver said. “You mus’ be one of the only ones left.”

The driver reached down, and then pulled up a thick manila envelope. He handed it to Michael. “Supposed to give you this.”

On the outside, was the logo of Wabash, Kramer & Moore, and inside was a binder of paper with a cover memorandum written by some first-year associate summarizing the contents.

It was Andie’s police file.

“Mind if we make an extra stop?”

“You got me for the night.” The driver pulled away.

When they merged into traffic, Michael briefly looked up from the papers at a group of people standing in line for a taxi.

That was when he saw him. Michael couldn’t remember the guy’s name, but they talked once or twice when he stayed at the resort. He loved using big words, and always wanted to play scrabble with other people in the cantina. He was odd, at the time, but the beaches around Playa del Carmen were filled with odd people, particularly the Sunset.

Shaped like a barrel—six foot, maybe just over, balding, goatee― every part of his body, from his legs to his neck to his fingers, was thick. That was really the best description for him: thick.

He must have been on the same flight as Michael, but how could he have missed him? Michael thought about asking the driver to stop, but then thought better of it. He didn’t know what he would do.

Michael stared as they drove past. And then, at the last possible moment, the thick man looked at Michael, smiled, and waved.

CHAPTER FIVE

Adjacent to LaGuardia Airport, ten mismatched buildings, collectively known as Riker’s Island, sat on a small patch of land in the middle of the East River. They housed over one hundred and thirty thousand men and women who had been arrested, imprisoned, or otherwise just plain thrown away. In the 1990s, the prisons on the island were so crowded that the mayor anchored a barge in the river to house another 800 inmates.

Riker’s Island was Andie Larone’s new home.

It had been almost ten years since Michael came to Riker’s Island every week as part of Columbia Law School’s free legal clinic, but the path through the island’s maze of buildings and service roads quickly came back to him.

He directed the driver down one street and up another until finally arriving at the building they wanted, the Rose M. Singer Center for Women. It was a squat concrete building put up in the late 1980s, and, as if to reflect the women who resided there, the outside of the building was a dirty, faded pink.

“I’m going to stay right here.” The driver slowed the Crowne Vic to a stop.

“Good,” Michael said. “I’m not sure if I can even get in at this hour.”

He collected the papers and put them back into the Wabash, Kramer & Moore envelope, and then took a breath. Michael tried to clear his mind, pushing Agent Vatch and everybody else to the side. He forced himself to concentrate on Andie. She deserved that much.

Michael got out and hustled toward the door. A hard wind came off the river and Michael conceded that the stewardess was right. He needed to buy a jacket.

The front door of the Singer Center closed behind him, and Michael walked up to the security desk. He told the guard who he was and who he wanted to see, but the large male guard didn’t move. He gave Michael a once over and said, “Do what now?”

###

A half dozen forms, four dirty looks, one condescending sneer, and a dismissive laugh later, he found himself in a small room set aside for attorneys and their clients. Michael sat in one of its two hard wooden chairs. A three-by-three graffitied table was between the chairs, pressed against and bolted to the wall. A plastic pitcher of warm water and two dirty glasses rested on the table, daring someone to take a drink.

Sitting alone and waiting, Michael read and reread the file.

Andie Larone was the strongest person he knew, man or woman. Like Michael, she didn’t have an easy time growing up. She was one of six kids, all removed by social services and shipped from one foster home to another. Some of the homes were good and some were very, very bad, but none were ever permanent. Andie learned to be independent before she learned her ABCs.

Even knowing Andie’s strength, Michael wasn’t sure how she would survive this. Seeing the case set forth in the police reports made Michael realize just how hard it was going to be to get her home.

Michael flipped through the papers and looked at the first two counts in the charging document: Count 1: First Degree Murder pursuant to Chapter 40 of the New York Penal Code Article 125; Count 2: Possession of an Illegal Substance with Intent To Sell pursuant to Chapter 40 of the New York Penal Code Article 220; Count 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and so on, fourteen counts in total. Each one was a quick jab to his stomach, getting stronger and harder as he went. By the end, the charges had blurred into a rapid succession of punches until finally Michael had to set the documents down and push them away.

He glanced back at the door, wondering what was taking so long.

He looked back at the papers spread out in front of him. He looked for a mistake, something the police had done that tainted the rest of the investigation. A mistake that would allow him to prevent the prosecutor from using the evidence found in Andie’s rental car at trial. In legal jargon, it was called “suppressing the fruit of a poisonous tree,” but it was more like a “get out of jail free” card in Monopoly.

The door buzzed and a bell rang.

Michael looked up.

“Andie,” he said, standing.

It had only been three days, but Andie looked pale. With no make-up, there was nothing to disguise the dark circles under her eyes. She hadn’t been sleeping.

Then, there was the necklace.

Andie’s simple necklace with the four beads and burnt gold key was gone, probably tucked away in a plastic bag somewhere with the rest of her clothes. He had never seen her without it.

Walking slowly through the door, Andie stopped a few feet in front of him as Michael came toward her. She put out her arms, and then wrapped around him. She squeezed tight for a second, and then melted.

Nothing felt more right, and Michael let the guilt and anxiety that had dogged him since the airport fade away. She was his only friend, and he was going to stay in New York for as long as it took. “Save her or die trying,” Michael thought, knowing it was a far more apt summary of the situation than he would ever admit to anybody, especially Andie.

CHAPTER SIX

In one of Michael’s first cases as a lawyer, he and Lowell Moore had defended a surgeon in a medical malpractice case. The surgeon had been in his mid-50s, and had performed thousands of surgeries, some big and some small. He had been well respected in the medical community and had even served as an adjunct professor at Mount Sinai School of Medicine―a success. And then, one day, he glances at a chart too quickly and amputates the wrong leg of a man with diabetes.

When Michael had asked questions about it, the surgeon was unemotional. “I made a mistake,” he had said, but there was no feeling in his eyes. There had been no remorse or empathy. Cutting people had become just a job; the unconscious body on the table was an inanimate object, not a father or a mother, or a grandfather or a friend. To him, cutting the wrong leg off had been the same as missing a meeting.

Michael sat across the table from Andie and felt like that surgeon. His emotions had been compartmentalized, and he went about his job, cutting and dissecting the facts presented to him and placing those facts within a legal framework. For the moment, he had convinced himself that it was the only way to help her. Although he knew, deep down, that wasn’t true.

Michael let Andie speak. Every question he asked was weighed against the need for information. It wasn’t about getting a complete record this time. It was about listening, digesting the facts. There would be time to circle back and fill-in the holes.

“They showed me photos,” Andie continued. “The cop called them the ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures.”

“Trying to shock you into saying something,” Michael said. He was tempted to continue his thought, but held back. “Did you recognize the man in the photos?”

“I don’t think so.” Andie’s eyes wandered away. “But I don’t know.”

“The file says that he came to the Sunset about five months ago, stayed four days, and then left.”

Andie shook her head. “Where’d they get that from? I don’t know who comes and goes. I just scribble the names in a guest book; sometimes I don’t even do that.”

Andie closed her eyes. A tear worked its way down her cheek. She rocked back and forth, and then became still. “This is bad,” she said. “Isn’t it? It’s bad.”

CHAPTER SEVEN

The dead guy in the photo was Helix Johannson, a drug dealer from the Netherlands who immigrated to the United States by stating that he would “invest” over a million dollars in the local economy, and, of course, pay a nice fee to the federal government in the process. It was a legalized form of bribery and bias deep within the immigration code, where rich foreigners leap-frogged over the thousands of other people who had been waiting for years to come into the country.

All you needed was an affidavit, a bank account statement, and a cashier’s check made out to Uncle Sam. God bless America.

Helix filed his papers in June 1989. A few months later he received his travel documents, a visa, and a brief letter from the State Department welcoming him to the greatest economy in the world.

To satisfy the immigration officials and the terms of his visa, Helix did invest. He set up a real estate company and bought properties in affluent neighborhoods in and around New York, Miami, Chicago, Dallas, Reno, and Los Angeles. They were the perfect tax write-off. They were also the perfect network of houses and apartments to distribute large quantities of pain killers, ecstasy, cocaine, and pot to his select clientele.

Helix wasn’t interested in dealing to people in poor neighborhoods. He hated poor people, and there were also far too many cops floating around in those neighborhoods as well as too many small-time hustlers looking to avoid jail time by ratting out the next guy higher-up in the chain. That guy would then rat out the next guy, who would then rat out the next guy, and on and on until they got to him.

Instead, Helix laid low. He kept the houses quiet, mowed the grass (which was all his new neighbors cared about anyway), and quietly serviced his growing list of customers.

They were, by and large, young rich kids who were killing time at college before landing a cushy job through a family friend upon graduation. They all had the cash advance PIN memorized for daddy’s credit card and a willingness to pay 35% above the street price, either because they didn’t know any better or liked the convenience of on-campus delivery.

It was all going smoothly until last year when a campus rent-a-cop busted a kid urinating outside the Beta Chi fraternity house at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. The kid was so high and freaked out that he started rattling off the names and addresses of every one of his fraternity brothers as well as the location of one of Helix Johannson’s properties.

The house was located in the nearby lily-white Dallas suburb of Highland Park. It was a two-story brick colonial with an immaculate yard, two car garage, and about a quarter-million dollars of marijuana and vicadin in the basement.

The discovery of that house had led to the discovery of another, and then another. The FBI had been called in to help, and shortly thereafter Helix Johannson had become a priority target.

The FBI had thought they had a tight net around him. Then he disappeared. Seven days later Helix was found with five bullet holes in his chest. Michael found it hard to believe that the FBI had lost him, but that was what the report stated. It wouldn’t be the first time that the FBI had messed up an investigation.

According to the police reports and the indictment, investigators believed that Helix Johannson had met Andie Larone at approximately 10:20 p.m. in an alley near West Fourth and Mercer by New York University.

An anonymous man supposedly witnessed the shooting from his apartment above, rushed down the stairs, and followed a “brown-haired woman” carrying two heavy suitcases to a Ford Taurus parked about three blocks away. The man called the license plate in to the police. The police tracked the license plate to a rental car company, and then to Andie Larone and the hotel where she was staying.

The police had gotten a warrant, the car had been searched, and inside they had found a gun and two suitcases filled with drugs and cash. As far as the police were concerned, the case was closed.

###

“Stop right here.” Michael pointed, and the driver pulled over to the curb. “Last stop before I call it a night, I promise.”

“Whatever,” the driver said, “just get me home before two.”

Michael grabbed his knapsack and got out of the car. It was nighttime now, and the financial district had lost its daytime hustle. The sidewalks were deserted, and it had somehow gotten even colder as gusts of wind howled down the empty avenues.

He crossed the street, walked up to the First National building on Vesey and Church, and then ducked inside.

When the large glass doors closed behind him, the sound of the wind was cut. It was silent, and Michael found himself in a cavernous art deco atrium designed in the late 1930s by architects Harvey Corbett and D. Everett Waid.

Polished black stone shot up five stories with inlaid images of Greek gods and goddesses blessing a Roman temple of commerce and the divine wisdom of unfettered markets. It was designed to inspire, and the architects were specifically instructed to ignore the stock market crash of 1929, the Midwest’s transformation from farms to dust, and the thirty-five percent of the country who had become card-carrying members of the Communist Party.

Michael walked up to the security desk. A man and a woman dressed in blue blazers adorned with plastic badges looked him over. Their nametags read Cecil and Flo, respectively, although no formal introductions were ever made.

“Can I help you?” Cecil asked.

“We’re closed for the night,” Flo added.

“I know you are closed,” Michael said, “but I was wondering if I could just ask you a few questions.”

“Give you a minute,” Cecil said.

“Maybe two,” Flo added.

“Before we ask you to leave.”

Michael took a breath, as he wondered whether Cecil and Flo had attended the same communication and customer service training as the guard at the Singer Center.

“I have a friend who came here, after hours, two nights ago,” Michael said. “She’s been accused of doing something, and I was wondering if I could look at your sign-in sheets.”

“To show that she was here,” Cecil said.

“Instead of there,” Flo added.

“Exactly. She signed-in, but the cops either didn’t follow-up or didn’t care.”

Cecil and Flo looked at one another, as if engaging in a telepathic argument regarding who would get up out of their seat to retrieve the daily log or whether they should both remain seated and do nothing.

Finally, Flo pushed her romance novel aside and with great effort began the process of extricating her body from the chair.

“What night you say?” Flo walked toward an unmarked door.

“Last Friday,” Michael said. “Her meeting was at 9:30 p.m., probably arrived a little after nine.”

Flo disappeared into a small back office that Michael had thought was a closet. He heard her shuffling papers, opening and closing file cabinets. Then he heard her sigh and say to herself, “Right here on top the whole time.”

Flo came back and handed Michael a folder containing two dozen pieces of paper. They were stapled together. “These are all of them?” Michael asked.

Flo shrugged her shoulders. “It’s what we got.”

Michael flipped through the pages, scanning the various entries. Nearly all of them were visitors who had arrived before five o’clock. The last sheet contained the list of people who had arrived after-hours. There were only eight names. Andie Larone was not one of them.

“There’s not another log?”

“That’s it, sugar,” Flo said.

“Who was she trying to see?” Cecil asked.

“Green Earth Investment Capital,” Michael said. “A man named Harold Bell. He’s a vice president there. Her resort was in trouble, and they were going to talk about refinancing and maybe bringing another investor to….” Michael’s voice trailed off, as Cecil and Flo shook their heads.

“Sure you in the right place?” Flo asked.

Michael told her the street address. “The First Financial Building.”

“Right,” Flo said.

“But no Green Earth here,” Cecil said. “You can check the directory, but I never heard of it.”

Continued….